New moon of August 2025 brings a rare black moon and a close Mars encounter

A rare black moon darkens the sky on Aug. 23, 2025, followed by a close encounter between the young crescent and Mars just days later.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

The new moon on Aug. 23 at 2:06 a.m. EDT (0606 UTC) is also a black moon, defined as the third new moon in a season that will see four new moons. Three days later, the moon will make a close pass to Mars in the evening sky.

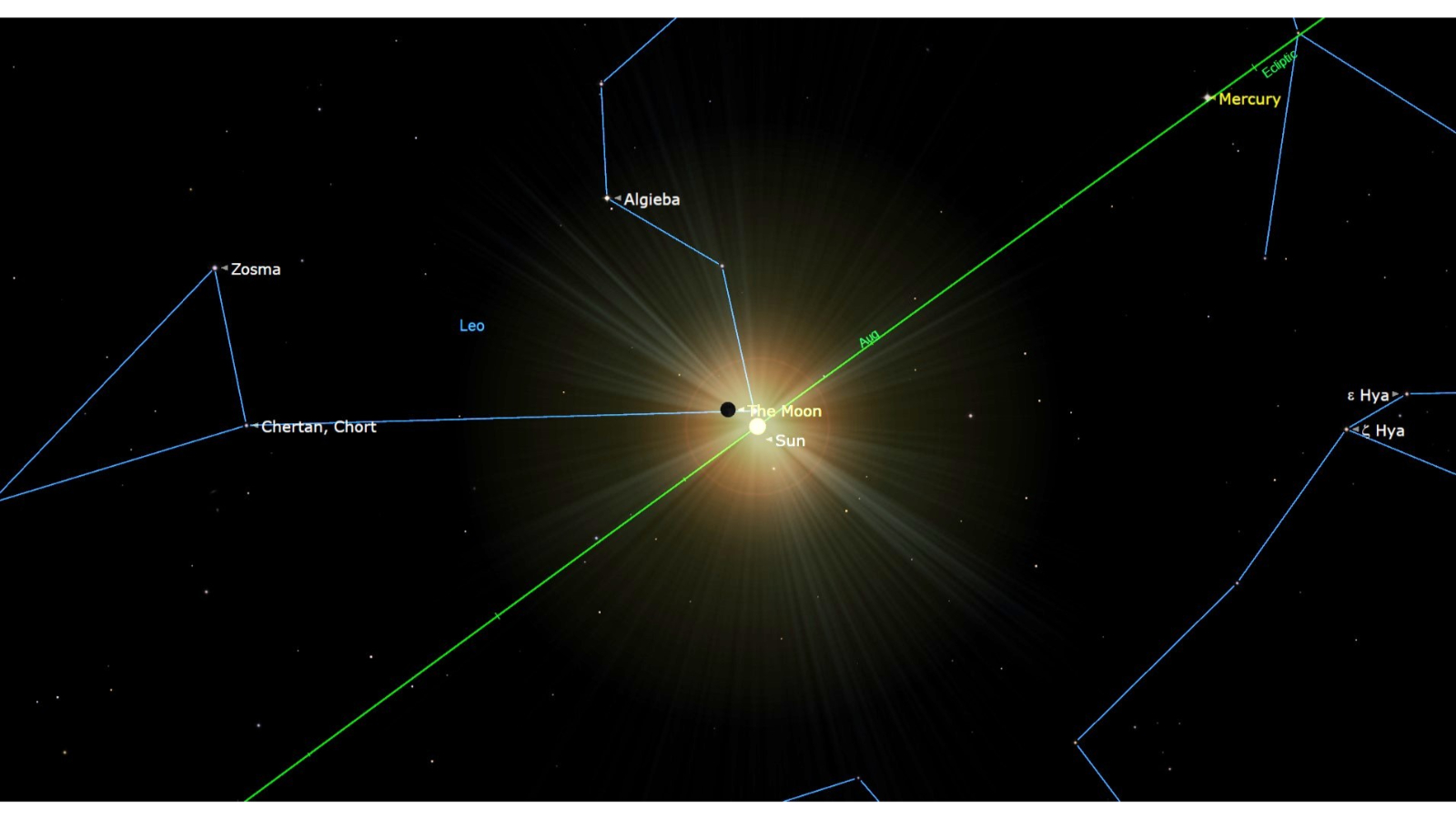

When the sun and moon share the same celestial longitude, you get a new moon. This is also called a conjunction (and the same term applies to other celestial bodies). As the illuminated side of the moon faces away from Earth, new moons are invisible to observers on the ground unless the moon passes directly in front of the sun — an eclipse. This doesn't happen every new moon because the moon's orbit is not perfectly aligned with the plane of the Earth's orbit; it is tilted about five degrees. (The next partial solar eclipse is on Sept. 21, and will be visible from the South Pacific, New Zealand, and Antarctica.)

Related: A rare Black Moon rises with the sun Aug. 23: Here's what to expect

Humans have used new moons in a wide range of calendrical systems to time the start of the month. Jewish, Islamic, Hindu, Māori and Chinese calendars all use them in this way, which shows not only how common it was, but that it clearly was practical enough for a wide range of locations.

The timing of lunar phases depends on the position of the moon relative to Earth, to find the time of the new moon locally, one can check how many hours from Universal Coordinated Time (or UTC) one's location is. For example, Eastern Daylight Time is four hours behind Universal Time, so the new moon is at 2:06 a.m. Phoenix is seven hours behind UTC on Mountain Standard Time (Arizona does not observe daylight savings time), so the new moon there is at 11:06 p.m. Aug. 22. Sydney, Australia, is 10 hours ahead, so the new moon is at 4:06 p.m. Aug. 23.

Conjunction of the moon and Mars

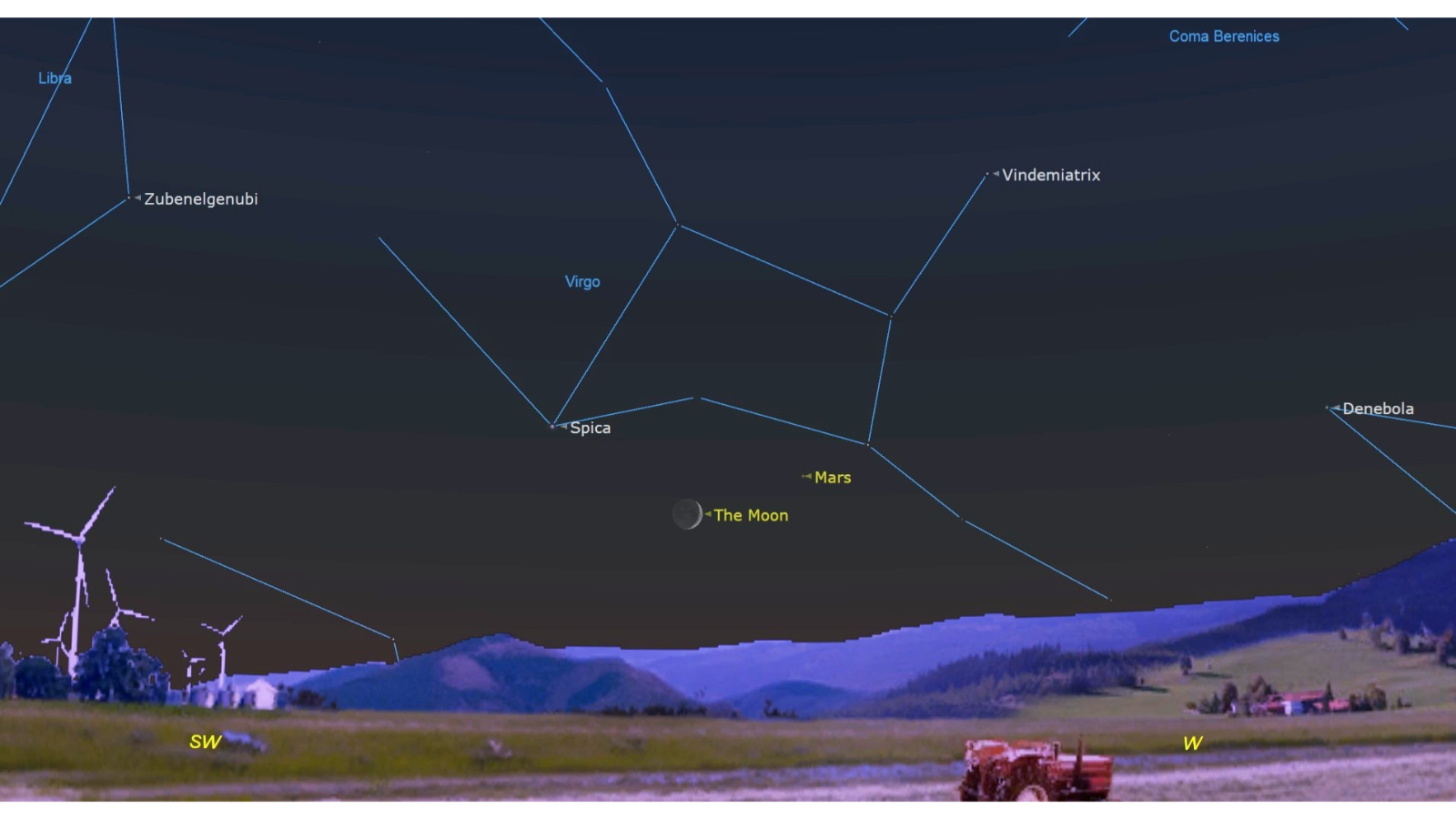

On Aug. 26, there is a conjunction of the moon and Mars, which happens at 12:41 p.m. EDT, so observers west of Greenwich, England, will not be able to see the conjunction itself as it is in the daytime. But looking at the western sky from New York on the evening of Aug. 26, one will see the three-day-old moon to the left of Mars, but both will be close to the horizon. At sunset, which is at 7:37 EDT, the moon will be just visible as a thin crescent in the southwest. Mars will be to the right of the moon, though it won't be really apparent until the sky gets a bit darker. Mars will be about 11 degrees high at 8:05 p.m. EDT (when civil twilight ends) and the moon will be about 9 degrees high. The moon sets at 9:02 p.m. while Mars sets at 9:07 p.m.

From locations further south, the moon and Mars will be higher in the sky; observers in Miami, for example, will see Mars about 19 degrees above the horizon by 8:09 p.m. EDT (the end of civil twilight). The moon will be at nearly the same altitude and to the left of Mars; even if Mars is hard to see, one can use the moon to locate it.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

From the Southern Hemisphere, the sun sets earlier as it is winter there; in Santiago, Chile, sunset is at 6:21 p.m. local time, and civil twilight ends at 6:46 p.m. At that point, Mars is fully 31 degrees above the western horizon and the thin crescent moon will appear above and to the left of it; it will look as though the round part of the crescent is pointing towards Mars. Mars sets at 9:19 p.m. local time and the moon follows at 9:48 p.m.

To see the actual conjunction, one must be east of the Greenwich time zone and southwards; for example, in Cairo, the conjunction is Aug. 26 at 7:41 p.m. local time. The moon will be 16 degrees high in the west and Mars will be about 19 degrees high and to the right of the moon. However, sunset is at 7:24 p.m., and at the moment of conjunction, the sky will still be relatively light (civil twilight does not end until 7:49 p.m.). Mars won't become readily visible until after that (though a good challenge is to see how soon after sunset one can spot it).

Prospects are better as one gets further south; in Nairobi, sunset is at 6:36 p.m. on Aug. 26. The conjunction is at 7:41 p.m. local time, as in Cairo, but the moon and Mars are higher in the sky when it is dark enough to see them both, a function of the earlier sunset. Civil twilight is at 6:57 p.m. and Mars is 30 degrees above the western horizon, with the moon to the left and just below it. This is just high enough where Mars is in the darker part of the sky, making it visible in a way that it isn't further north. By the time of conjunction, Mars is as high as in Cairo (19 degrees) but the sky is darker and both Mars and the moon are clearly visible among the surrounding stars. The two will set by 8:57 p.m. and 8:55 p.m., respectively.

From Cape Town, the conjunction is at 6:41 p.m. local time, and given that it is in the Southern Hemisphere's mid-latitudes, sunset is relatively early, at 6:24 p.m. and civil twilight is at 6:49 p.m. A thin crescent moon with the "horns" facing upwards will be about 34 degrees high in the west when the conjunction happens, with Mars to the right at 33 degrees. Mars sets first at 9:23 p.m. and the moon follows at 9:28 p.m.

Visible planets

On the night of the new moon itself (Aug. 23) from New York City, Mars will be low in the western sky after sunset (which is at 7:42 p.m. EDT). The Red Planet will only be about 16 degrees above the horizon at sunset, and by 8:10 p.m. (the end of civil twilight), it will be only 11 degrees high, and still hard to see against the sky. Mars sets at 9:15 p.m.

Want to view the night sky up close? The Celestron NexStar 8SE is ideal for beginners wanting quality, reliable and quick views of celestial objects. For a more in-depth look, check out our Celestron NexStar 8SE review.

Just before Mars sets, Saturn rises at 8:55 p.m. EDT. By about 10:30 p.m., it will be 17 degrees above the southeastern horizon. Given that the planet is in the constellation Pisces, which has few bright stars, it will be easy to pick out. The planet crosses the meridian (or transits) at 2:50 a.m. on Aug 24 and sets after sunrise at 8:45 a.m. EDT. At transit, Saturn will be about 47 degrees high in the south.

As Saturn approaches transit, Jupiter rises at 2:29 a.m. Aug. 24. Jupiter is in Gemini, and to the left of Jupiter, one can see Castor and Pollux forming a triangle; Castor is the uppermost of the three. Venus rises at 3:29 a.m. and is the brightest object in the sky; it outshines stars and, as such, is easy to find. By 4:30 a.m. Jupiter and Venus are respectively 20 degrees and 10 degrees above the eastern horizon.

The last planet to rise is Mercury, which reaches its highest altitude in the predawn sky on Aug. 21. On the morning of Aug. 24, the planet rises at 4:47 a.m. EDT. By 5:30 a.m., one can see Jupiter, Venus and Mercury forming a line in the sky — Mercury is at about 8 degrees above the eastern horizon. It will still be hard to see, but if one starts looking soon after it rises, one can spot it; a line between Jupiter and Venus towards the horizon hits it, Jupiter will be almost directly above Venus and slightly to the right of it.

From the Southern Hemisphere, Mars is higher in the sky in the evening, both because the sun sets earlier and the "upside-down" orientation of the sky. From Santiago, Chile, sunset on Aug. 23 is at 6:19 pm. local time and by 7 p.m., the sky is getting dark; Mars will still be 29 degrees high in the west-northwest; the planet sets at 9:21 p.m. As in the northern latitudes, Saturn rises as Mars sets, in this case at 8:31 p.m. The ringed planet transits at 2:36 a.m. Aug. 24. Jupiter rises at 4:44 a.m. in the east-northeast. Venus rises at 5:28 a.m. and Mercury at 6:23 a.m. Mercury is actually placed poorly for Southern Hemisphere sky watchers; even though sunrise isn't until 7:10 a.m. in Santiago, Mercury will only get to an altitude of about 4 degrees by the time civil twilight begins at 6:44 a.m., so it is a difficult observing target. One can still use Jupiter and Venus to find it, though, except that the line they make is at a steeper angle (about 45 degrees) and Jupiter is to the left of Venus instead of the right as one faces east.

Constellations

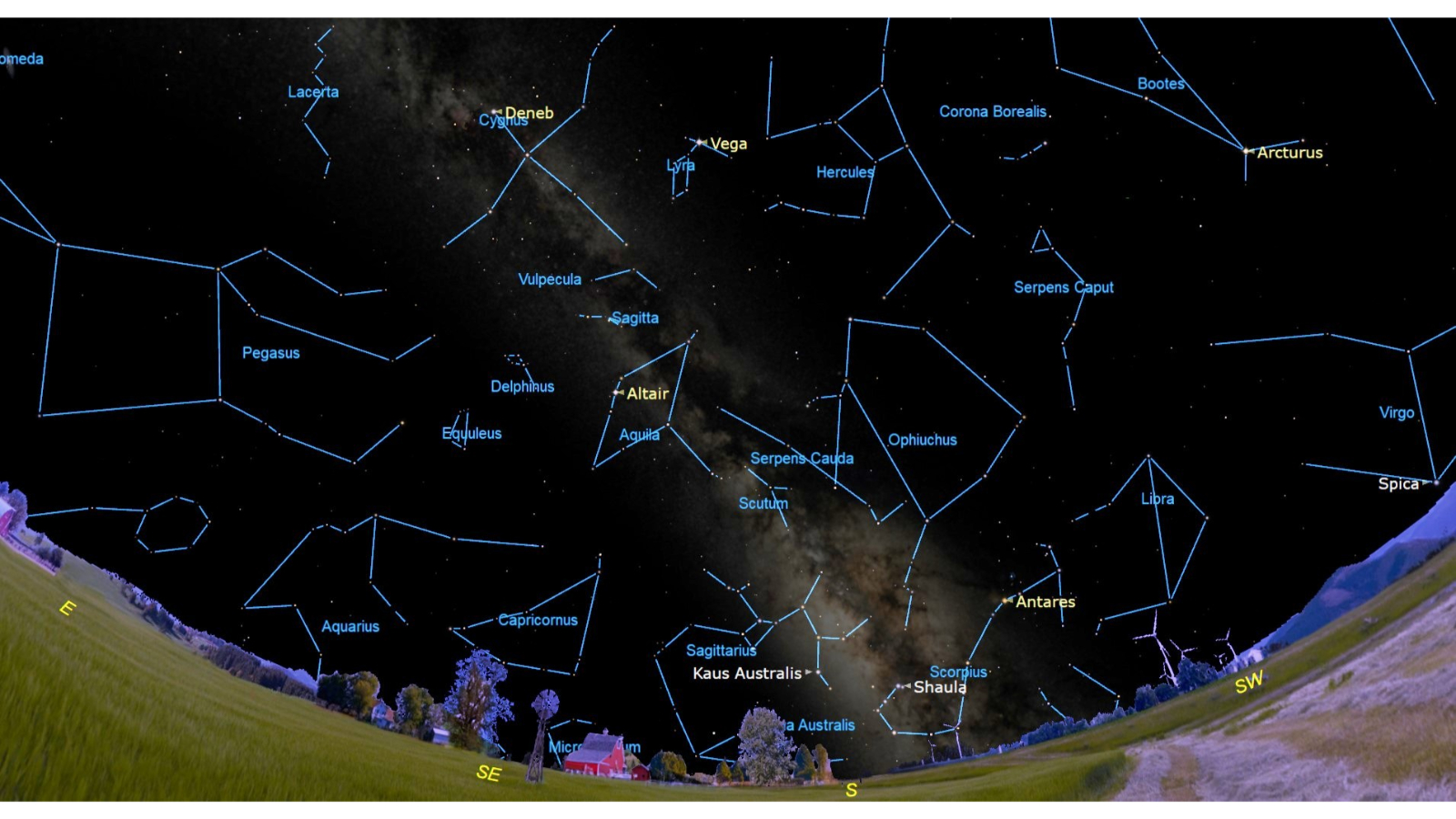

In late August, Northern Hemisphere observers can see constellations of three seasons — traditional summer, autumn and winter. A dark sky location also offer the chance to see two different sides of the Milky Way.

By about 9 p.m. on Aug. 23, the sky is completely dark, and even from city locations it's possible to see the constellations Lyra, Cygnus and Aquila, high in the southeast. Lyra is the highest, and the easiest to find because one needs only to look almost straight up to see Vega, its brightest star, about 85 degrees high at the latitude of New York City, Chicago, or Sacramento.

If one looks left (east) of Vega, about a third of the way towards the horizon, one sees Deneb, the alpha star of Cygnus the Swan. Just to the right of Deneb is a medium-bright star called Sadr (or Gamma Cygni) that is the center of the cross-shape that defines the bird, with one wing ending upwards at the star Delta Cygni and the other below at Epsilon Cygni (called Aljanah). Go to the right from Sadr and you end at the second-brightest star in Cygnus, called Albireo (Beta Cygni).

Further southwards, towards the horizon and to the right of Vega is Altair, the eye of Aquila, the Eagle. Vega, Deneb and Altair make a right triangle with the right angle at Deneb, this is called the Summer Triangle. From a darker sky site one can see the Milky Way, the misty band of light that shows the edge of our galaxy, and in the direction of Cygnus, one is looking towards the galactic east, about 90 degrees away from the center.

Draw a line through Deneb and Altair and you are going south, and just above the southern horizon, you hit the "teapot" shape of stars that is Sagittarius, the Archer. To the right of Sagittarius (westwards) is Scorpius the Scorpion, and you can recognize it because Antares, its brightest star, has a distinct red-orange hue. Antares will be about 17 degrees high. Here you are looking towards the galactic center. One can use Antares to spot the claws of Scorpius — three stars that form a roughly vertical line to the right (west) of Antares. From there, one can go back to Antares and trace a curved line of fainter stars that form the Scorpion's back and tail.

Turn so that Antares is directly behind you and you are facing north. On the left side of the sky is the Big Dipper, part of the Great Bear, Ursa Major. The "bowl" of the dipper points upwards and to the right, and one can follow the two stars in the front of the bowl to Polaris, the Pole Star. The two stars will be on the bottom side of the bowl at that point in the evening. Using the handle of the Dipper one can "arc to Arcturus" by tracing a sweeping arc along the handle to the first bright star one encounters. Arcturus is the brightest star in Boötes, the Herdsman. Opposite the Big Dipper, about the same distance to the right (eastwards) of Polaris and about 30 degrees high (a third of the way from the horizon to the zenith), is Cassiopeia, a W-shaped group of stars, representing the legendary Queen of Ethiopia and the mother of Andromeda.

By midnight, the Summer Triangle has moved to the western side of the sky, and if one looks at Cassiopeia and turns right, towards the are above Saturn, one can see large square of stars called (rather unimaginatively) the Great Square. The three stars that will be on the right side of the square are the wings of Pegasus, the winged horse ridden by Perseus the Hero.

The left corner of the square, meanwhile, is the head of Andromeda, who, according to legend, Perseus was saving from the leviathan Cetus (also called the Whale). Cetus is just rising, and below Saturn and Pisces. The easiest way to find it (as it is not a bright constellation) is to look down from Saturn about halfway to the horizon, and one encounters Diphda, or Beta Ceti. Perseus, meanwhile, is below Cassiopeia; one can recognize it by looking towards the horizon from Cassiopeia and slightly to the right; the brightest star in Perseus, called Algenib, is about 29 degrees high. All of these constellations appear earlier in the evening as summer turns into fall.

By 3 a.m., one can look to the east and see Taurus the Bull, with the head of the bull marked by Aldebaran, a bright orange star that will be about 30 degrees high. Looking to the north of Taurus (to the left), one can see a bright star a bit higher than Aldebaran, at about 37 degrees, called Capella, in the constellation Auriga, the Charioteer. Look down from Aldebaran and close to the horizon is Betelgeuse, the bright reddish shoulder of Orion. All three constellations are associated with the winter sky. The Milky Way continues here through Auriga, Perseus, and Cassiopeia; the direction of Auriga is towards intergalactic space, exactly opposite the galactic center seen in Sagittarius.

From mid-southern latitudes by 8 p.m., one will see Crux, the Southern Cross, about 36 degrees high in the southwest. Above it is Alpha Centauri and the constellation Centaurus, the Centaur. (You can find Alpha Centauri by drawing a line up along the crossbar of the Cross).

Below the Cross and extending to the southern horizon are Carina, the Keel and Vela, the sail, two of the constellations that make up the ship Argo, which Jason sailed. Vela is a rough oval of 10 stars, though only eight are readily visible from more urban locations and by 8 p.m., some have set.

Antares is towards the southwest, but it is almost directly overhead, at an altitude of 75 degrees. The curve of the Scorpion's back and tail leads to a point near the zenith, and a medium-bright star called Shaula (Lambda Scorpii). Directly below Shaula is another star in Scorpius called Gitab (Theta Scorpii) and as one continues to look towards the horizon (and approaches the Southern Celestial Pole), one encounters Atria, the brightest star in Triangulum Australe, the Southern Triangle. To the left of the Triangle is Pavo, the Peacock, though the constellation is fainter and hard to see from urban areas. If one keeps looking towards the horizon and eastwards (left) one encounters a bright star in the east-southeast, this is Fomalhaut, the alpha star of Piscis Austrinus, the Southern Fish. It is not only one of the brightest stars in the sky but a close neighbor of the solar system, only 25 light-years away.

Jesse Emspak is a freelance journalist who has contributed to several publications, including Space.com, Scientific American, New Scientist, Smithsonian.com and Undark. He focuses on physics and cool technologies but has been known to write about the odder stories of human health and science as it relates to culture. Jesse has a Master of Arts from the University of California, Berkeley School of Journalism, and a Bachelor of Arts from the University of Rochester. Jesse spent years covering finance and cut his teeth at local newspapers, working local politics and police beats. Jesse likes to stay active and holds a fourth degree black belt in Karate, which just means he now knows how much he has to learn and the importance of good teaching.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.