New moon calendar 2026: When is the next new moon?

The dark skies during a new moon provide ideal conditions for spotting skywatching targets that would otherwise be outshone by moonlight.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

When is the next new moon?

The next new moon occurs on March 18 at 9:23 p.m. EDT (0223 GMT (March 19))

A new moon occurs when the moon is directly between Earth and the sun, with its shadowed side pointing towards us. You can see a new moon when it crosses the face of the sun during a solar eclipse.

New moons occur approximately once every month because that's roughly how long it takes for the moon to orbit Earth. But because the moon's orbit is slightly tilted relative to Earth's orbit around the sun, it doesn't block out the sun on every orbit, hence why not every new moon results in a solar eclipse, according to NASA.

Related: What you can see in the night sky tonight

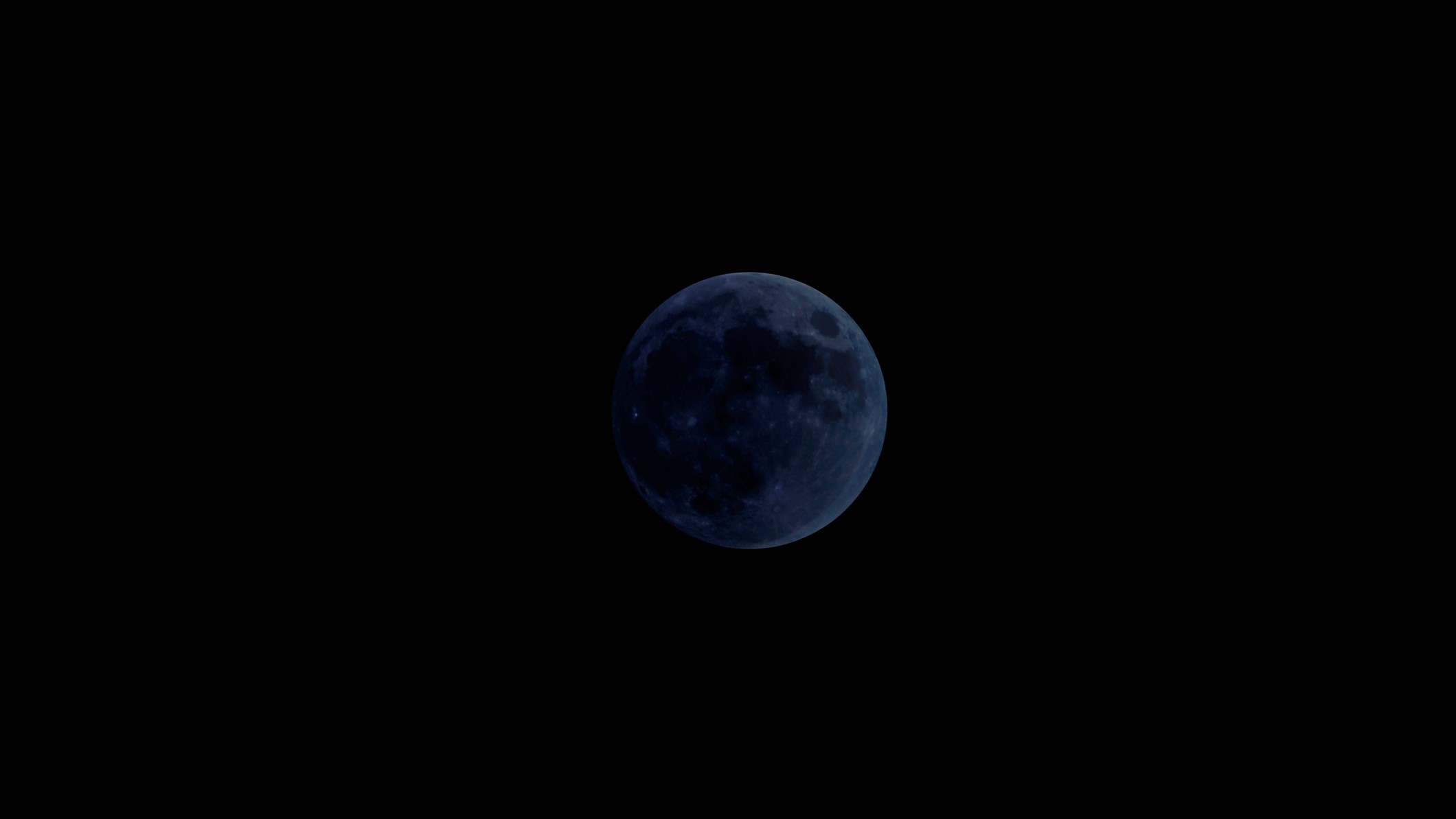

On the nights before and after a new moon, when just a thin crescent is present, it is sometimes possible to make out the stunning effect known as Earthshine, or Da Vinci glow.

During this time, it appears as though you can see the entire disk of the moon dimly illuminated with an almost bluish-gray glow, along with the brightly lit crescent. As such, the term Earthshine is sometimes referred to as "The old moon in the new moon's arms." The glow is produced by light from a fully illuminated Earth reflecting off the lunar surface. Space.com's skywatching columnist Joe Rao explains the phenomenon in more detail in this interview conducted with FoxWeather.com.

Every so often a new moon is known as a "Black Moon". A Black Moon is not an official astronomical term but there are two common definitions for the term according to Time and Date:

- The second new moon in a single calendar month.

- The third new moon in a season of four new moons.

The next black moon will occur on Aug. 31, 2027, as per the first definition of the second new moon within a single calendar month.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Looking for a telescope to observe the moon or anything else in the sky? We recommend the Celestron Astro Fi 102 as the top pick in our best beginner's telescope guide. Don't forget a moon filter!

Looking for a telescope or binoculars to observe the moon? Our guides for the best binoculars deals and the best telescope deals now can help. Our best cameras for astrophotography and best lenses for astrophotography can also help you prepare to capture the next lunar skywatching sight.

If you fancy taking a more in-depth moonlit tour of our rocky companion, our ultimate guide to observing the moon will help you plan your next skywatching venture whether it be exploring the lunar seas, mountainous terrain or the many craters that blanket the landscape.

Related: 21 amazing dark sky reserves around the world

When is the new moon? Calendar dates for 2026

This is when new moons will occur through 2026, according to NASA.

Date | U.S. Eastern time | U.K. time |

|---|---|---|

Jan. 18 | 2:52 p.m. (EST) | 7:52 p.m. (GMT) |

Feb. 17 | 7:01 a.m. (EST) | 1201 GMT |

March 18 | 9:23 p.m. (EDT) | 0223 GMT (March 19) |

April 17 | 7:52 a.m. (EDT) | 1252 BST |

May 16 | 4:01 p.m. (EDT) | 2101 BST |

June 14 | 10:54 p.m. (EDT) | 0354 BST (Jun. 15) |

July 14 | 5:43 a.m. (EDT) | 1043 BST |

Aug. 12 | 1:37 p.m. (EDT) | 1837 BST |

Sep. 10 | 11:27 p.m. (EDT) | 0427 BST (Sep. 11) |

Oct. 10 | 11:50 a.m. (EDT) | 1650 BST |

Nov. 9 | 2:02 a.m. (EST) | 0702 GMT |

Dec. 8 | 7:52 p.m. (EST) | 0052 GMT (Dec. 9) |

Moon phases

As the moon orbits Earth, it reflects sunlight and appears to cycle through eight distinct phases:

New moon: The moon is between Earth and the sun, and the side of the moon facing toward us receives no direct sunlight; it is lit only by dim sunlight reflected from Earth.

Waxing crescent: As the moon moves around Earth, the side we can see gradually becomes more illuminated by direct sunlight.

First quarter: The moon is 90 degrees away from the sun in the sky and is half-illuminated from our point of view. We call it "first quarter" because the moon has traveled about a quarter of the way around Earth since the new moon.

Waxing gibbous: The area of illumination continues to increase. More than half of the moon's face appears to be getting sunlight.

Full moon: The moon is 180 degrees away from the sun and is as close as it can be to being fully illuminated by the sun from our perspective. The sun, Earth and the moon are aligned, but because the moon’s orbit is not exactly in the same plane as Earth’s orbit around the sun, they rarely form a perfect line. When they do, we have a lunar eclipse as Earth's shadow crosses the moon's face.

Waning gibbous: More than half of the moon's face appears to be getting sunlight, but the amount is decreasing.

Last quarter: The moon has moved another quarter of the way around Earth, to the third quarter position. The sun's light is now shining on the other half of the visible face of the moon.

Waning crescent: Less than half of the moon's face appears to be getting sunlight, and the amount is decreasing.

Finally, the moon is back to its new moon starting position. Now, the moon is between Earth and the sun. Usually, the moon passes above or below the sun from our vantage point, but occasionally it passes right in front of the sun, and we get a solar eclipse.

Floating 3D Moon Night Light Lamp | RRP $239.97 | Now: $139.97

If you know someone who can't get enough of the moon, then they'll be delighted with this floating 3D lamp from encalife. Using magnetic levitation technology, the realistic globe will project "moonlight" as it floats and spins in mid-air. Comes in three color modes and wireless LED charging.

New moon FAQs answered by an expert

We asked meteorologist Joe Rao a few commonly asked questions about the new moon.

Joe Rao is Space.com's skywatching columnist, as well as a veteran meteorologist and eclipse chaser who also serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium.

What's the difference between a new moon and a full moon?

When the moon is at its new phase it is positioned between the sun and the Earth and appears in close proximity to where the sun is in our sky. So a new moon appears to rise and set with the sun and is invisible because sunlight is falling on that part of the moon that is turned away from us. We call it a "new" moon, because the cycle of phases that the moon displays to us takes 29.53 days to complete, and is known as a synodic month. The word synodic is derived from the Greek "sunodos" which literally means "meeting." And indeed, at roughly 29½-day intervals, the moon "meets" the sun and the cycle of lunar phases starts anew (hence we have a "new" moon).

In contrast, a full moon appears opposite to the sun in the sky. So it rises at sunset, appears highest in the middle of the night and sets at sunrise. The side of the moon that is turned toward Earth is fully illuminated, hence the term "full" moon.

How long does a new moon last?

Astronomers calculate the moment of a new moon based on its position in the sky relative to the sun. When both the sun and the moon have the same right ascension (the distance of a point east of the vernal equinox, measured along the celestial equator and expressed in hours, minutes, and seconds) that is the time of a new moon. Since the moon is constantly moving in its orbit around the Earth, a new moon only lasts for a moment. However, to be able to see the moon is another matter; we usually must wait at least 18-24 hours after the new moon to allow it to move far enough away from the sun. We then see it low in the western sky appearing as a lovely crescent phase and setting an hour or two after sunset.

There is another way to see a new moon: When it passes directly in front of the sun to produce a solar eclipse. Then, the dark disk of the new moon — normally unseen every month — is visible in silhouette, passing across the face of the sun.

The man who was known as "the world's greatest nonprofessional astronomer," Leslie C. Peltier (1900-1980), once noted that "Only during an eclipse of the sun can we note the instant when the old moon, moving eastward, crosses the median line of the sun and becomes a fresh new moon just starting out on another monthly lifetime."

How often do we experience a new moon?

Usually once a month, although if a new moon happens on the first or second day of the month, a second new moon is likely to occur at the end of the month. Only in the month of February is it possible not to have a new moon. This can happen because even in years where there is a leap day, February can have no more than 29 days. But because a synodic month lasts about 29.5 days, we can have a new moon on January 30 or 31, but the very next new moon would not occur until March 1; completely bypassing February! Such an odd circumstance will happen in the year 2033.

Additional resources

NASA's SkyCal Events Calendar offers a comprehensive calendar of moon phases, lunar and solar eclipses and more for the entire calendar year.

Editor's Note: If you snap a photo of the moon and would like to share it with Space.com's readers, send your photo(s), comments, and your name and location to spacephotos@space.com.

Bibliography

When Is the Next Black Moon? Time and Date,

https://www.timeanddate.com/astronomy/moon/black-moon.html

When and where to spot the 'Di Vinci Glow', Fox Weather, https://www.foxweather.com/watch/play-6669f25650000cb

Lunar Phases, NASA, https://solarsystem.nasa.gov/moons/earths-moon/lunar-phases-and-eclipses/#otp_what_are_lunar_phases?

Daisy Dobrijevic joined Space.com in February 2022 having previously worked for our sister publication All About Space magazine as a staff writer. Before joining us, Daisy completed an editorial internship with the BBC Sky at Night Magazine and worked at the National Space Centre in Leicester, U.K., where she enjoyed communicating space science to the public. In 2021, Daisy completed a PhD in plant physiology and also holds a Master's in Environmental Science, she is currently based in Nottingham, U.K. Daisy is passionate about all things space, with a penchant for solar activity and space weather. She has a strong interest in astrotourism and loves nothing more than a good northern lights chase!

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.