Astronomers detect rare 'free floating' exoplanet 10,000 light-years from Earth

"Our discovery offers further evidence that the galaxy may be teeming with rogue planets."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Rogue planets — worlds that drift through space alone without a star — largely remain a mystery to scientists. Now, astronomers have for the first time confirmed the existence of one of these starless worlds by pinpointing its distance and mass — a rogue planet roughly the size of Saturn nearly 10,000 light-years from Earth.

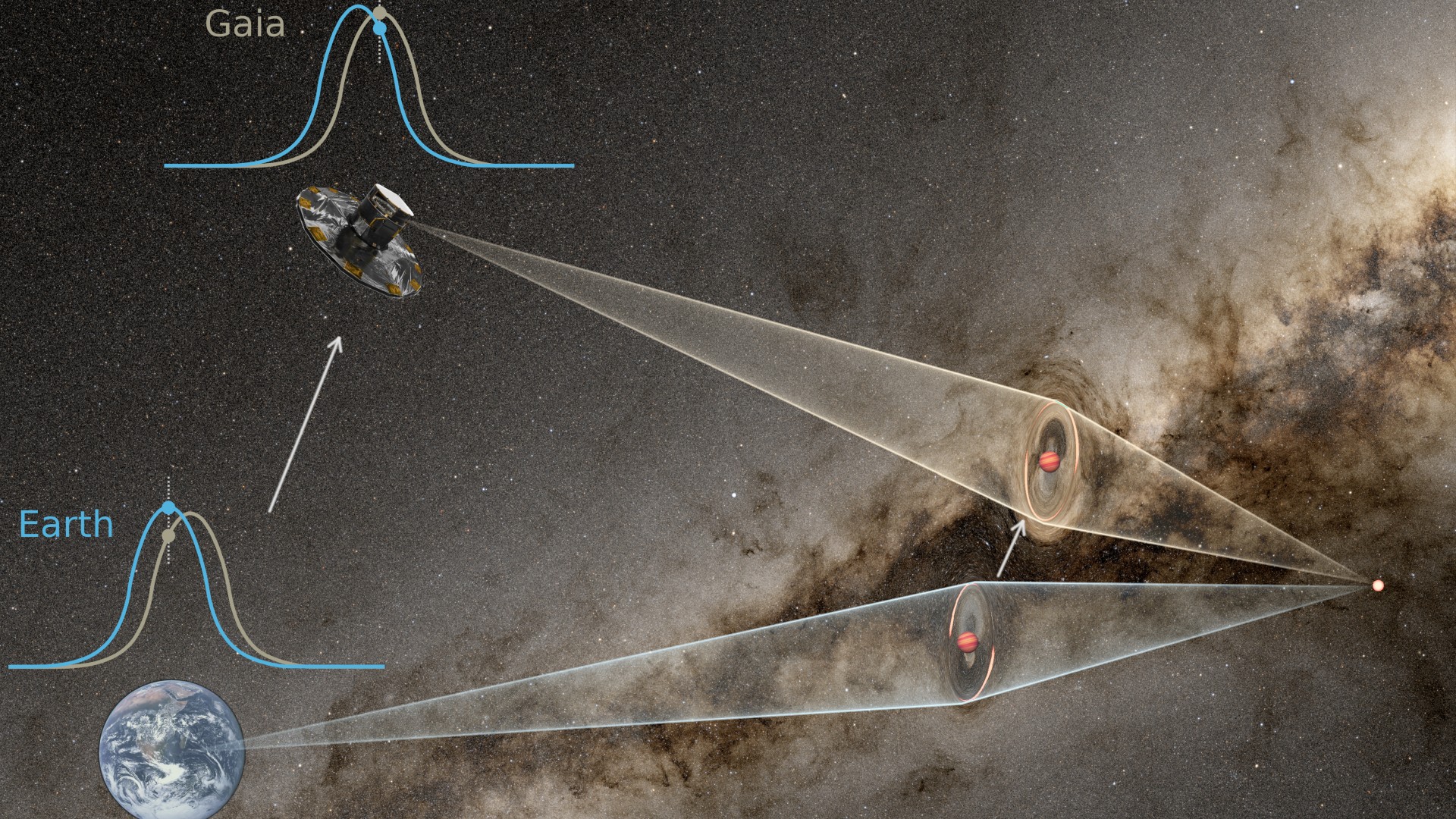

Planets are typically found bound to one or more stars. However, in 2000, astronomers detected the first signs of a "rogue planet" — a free-floating world that orbited no star. Then, in 2024, researchers detected an object distorting the light from a distant star, simultaneously from both Earth and space using several ground-based observatories as well as the European Space Agency's now-retired Gaia space telescope. These observations helped scientists estimate that the object was a newfound world found about 9,950 light-years from Earth in the direction of the Milky Way's center, with a mass about 70 times larger than Earth. (Saturn, on the other hand, is about 95 Earth masses.)

The researchers behind the discovery say these types of free-floating planets should be even more abundant throughout our home galaxy than we realize. "Theoretical studies of formation of planetary systems suggest that they should be very numerous in the Milky Way, even a few times more numerous than the number of stars in the galaxy," study co-author Andrzej Udalski, an astrophysicist at the University of Warsaw in Poland, told Space.com.

More data on rogue planets could help shed light on how all planets form, and how and which kinds go rogue. Previous research suggests that chaotic interactions between worlds early in the development of planetary systems around stars can sling planets outward. Passing stars may also disrupt planetary systems, hurling worlds into the void. In addition, some rogue planets may form directly by themselves from the same clouds of gas and dust that birth stars.

Rogue planets are difficult to spot because they do not emit enough light for the current generation of telescopes to detect. Right now, the only way to discover these wandering worlds is with the help of gravitational fields, which warp the fabric of spacetime.

When a rogue planet drifts in front of a star, the world's gravitational field can act like a lens, amplifying the star's apparent brightness and letting astronomers infer the rogue planet's existence. Up to now, researchers detected about a dozen potential rogue planets with this method.

One limitation of using such "gravitational microlensing" to detect rogue planets is that it cannot by itself reveal how far away these worlds are. This in turn makes it difficult to deduce other features of those planets, such as their masses. As such, much about rogue planets remained a matter of speculation — astronomers could not even conclusively confirm they were actually planets and not more massive bodies, such as the failed stars known as brown dwarfs.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Now, astronomers have not only detected a rogue planet, but also pinpointed its distance and its mass. By viewing this event, known as both KMT-2024-BLG-0792 and OGLE-2024-BLG-0516, from two different vantage points, the scientists could essentially triangulate its distance from Earth. Once they had a better idea of its distance from Earth, they could then estimate its mass, based on how long its gravitational field distorted the light the astronomers saw.

"Our discovery offers further evidence that the galaxy may be teeming with rogue planets," study co-author Subo Dong, a professor of astronomy at Peking University in China, said in a statement.

The next generation of space telescopes may detect even more rogue planets. For instance, NASA's Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope, which may launch in 2026, will scan huge swaths of the sky in infrared light 1,000 times faster than NASA's Hubble Space Telescope. China's Earth 2.0 satellite, planned for launch in 2028, will also search for free-floating planets.

"The future of free-floating planet science looks very bright," Udalski said.

The scientists detailed their findings online Jan. 1 in the journal Science.

Charles Q. Choi is a contributing writer for Space.com and Live Science. He covers all things human origins and astronomy as well as physics, animals and general science topics. Charles has a Master of Arts degree from the University of Missouri-Columbia, School of Journalism and a Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of South Florida. Charles has visited every continent on Earth, drinking rancid yak butter tea in Lhasa, snorkeling with sea lions in the Galapagos and even climbing an iceberg in Antarctica. Visit him at http://www.sciwriter.us

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.