A 'cold Earth' exoplanet just 146 light-years away might be in its star's habitable zone — if it exists

A planet that may exist, and may be habitable or may be frozen, has been discovered on an Earth-like orbit around a star 146 light-years away

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

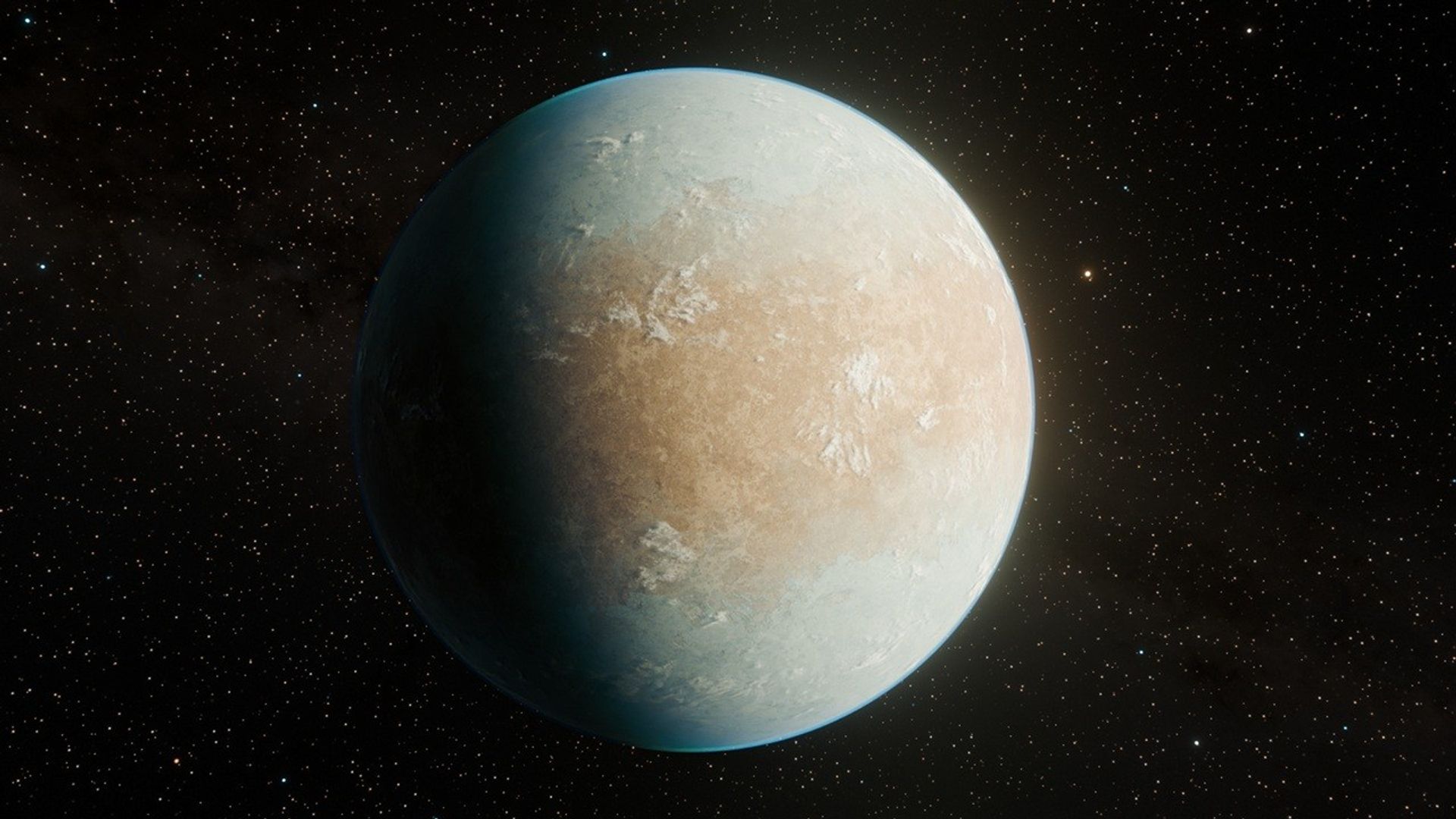

A possible rocky exoplanet referred to as a 'cold Earth' that could orbit on the outer edge of the habitable zone has been found around a star 146 light-years away.

Known as HD 137010b, the exoplanet is considered at this stage to be a candidate world, meaning that its existence has yet to be confirmed. The star is a K-type dwarf, meaning it is a little smaller, dimmer and cooler than our sun, and HD 137010b would receive just 29% of the heat and light that Earth does from our sun. Based on our best estimates of the size of its star, the planet likely has a diameter just 1.06 times that of Earth, and orbits once every 355 days, although there's a huge amount of uncertainty in that estimation. This imprecision means that exactly what conditions are like on the planet's surface remain open to debate.

Based on its orbital period of 355 days, HD 137010b is right on the very edge of its star's habitable zone. The planet's surface is likely frozen, unless it has a much thicker atmosphere than Earth does. If it has no atmosphere at all, then its average surface temperature would be –90 degrees Fahrenheit (–68 degrees Celsius) which is marginally colder than Mars (where the average temperature is –85 degrees Fahrenheit(–65 degrees Celsius).

Article continues belowA team of astronomers led by Alexander Venner at the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy in Germany came across this 'maybe' planet while sifting through archive data from the Kepler Space Telescope's K2 mission, which ended in 2018.

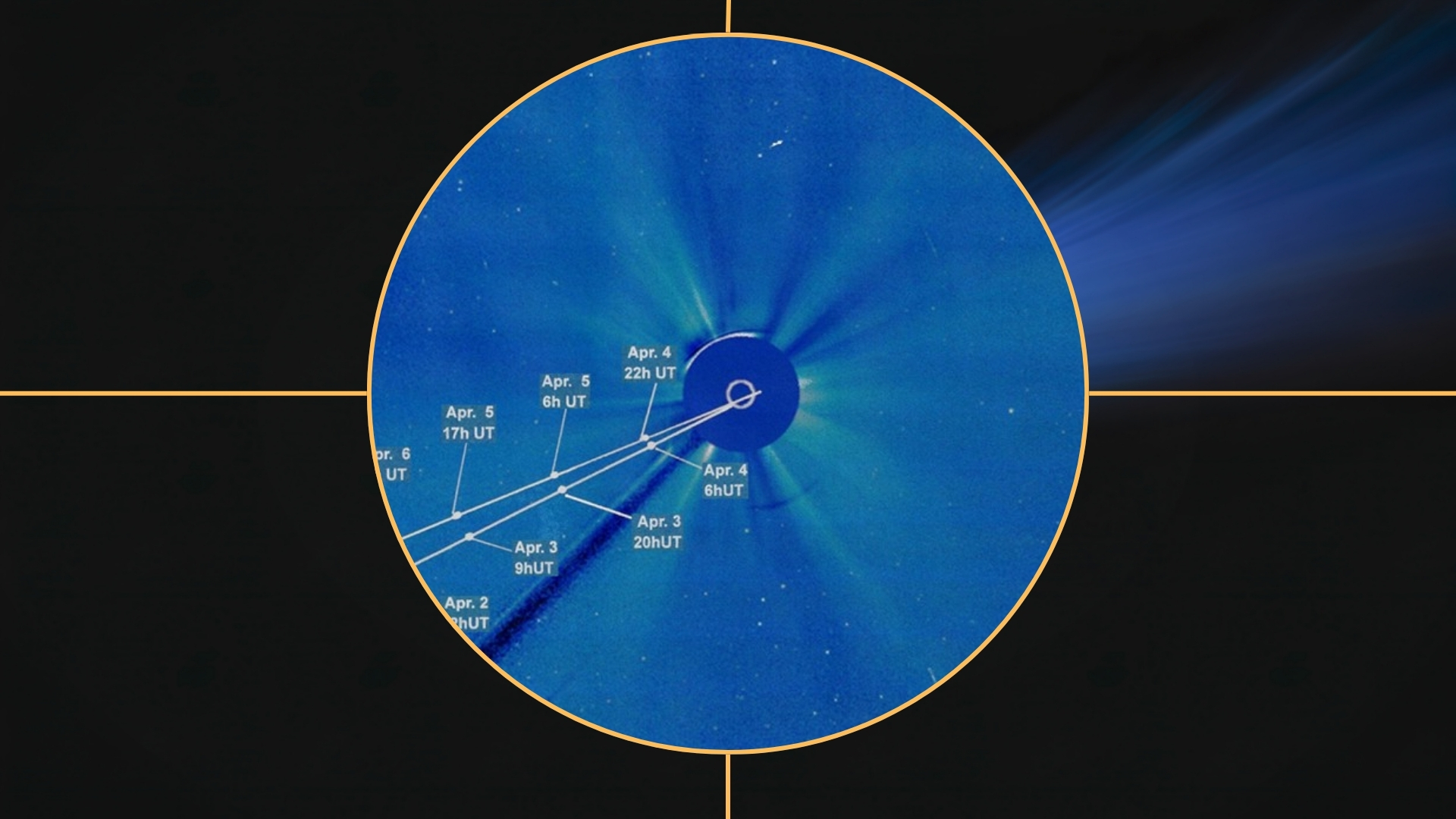

Venner's team only found one transit of HD 137010b (one instance of it passing in front of its host star) that lasted ten hours, but were able to rule out the usual false positives, such as stellar activity causing the star to dim, by using new and historical images, as well as observations by other observatories. Usually it takes a minimum of two or three transits to confirm a planet's discovery.

Because HD 137010b transits a relatively bright star in our sky, there's hope that instruments such as the James Webb Space Telescope will be able to search for an atmosphere around the planet. Most of the stars observed by Kepler were fainter than magnitude 13 in our sky, so HD 137010b's star is an outlier at magnitude 10, bringing it in range of even 6-inch (150mm) amateur telescopes. For professional observatories, magnitude 10 is easy.

Why do we need a bright star to learn more about HD 137010b? Because astronomers can detect the atmosphere of an exoplanet based on the light that passes through it at two different points in the planet's orbit.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

One point occurs when it is transiting, during which the star's light is filtered through the planet's atmosphere and is absorbed at wavelengths corresponding to atmospheric molecules. The second point is when the planet is hidden behind the star, so the light of just the star can be subtracted from the light of the star and planet together, leaving just the light from the planet. Either way, this requires a bright star to produce a signal large enough to be convincing.

The problem is that with an orbital period of somewhere around 355 days, transits of HD 137010b don't come along very often, and without knowing the orbital period precisely, astronomers don't know when to look for the next transit. However, if NASA's TESS (Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite) or the European Space Agency's CHEOPS (Characterising ExOPlanets Survey) don't observe a transit, then ESA's forthcoming PLATO (PLAnetary Transits and Oscillations) mission, which is scheduled for launch in December 2026, stands a very good chance of detecting HD 137010b.

And what could PLATO find? There's actually a host of possibilities for HD 137010b and we shouldn't write it off as a frozen Earth just yet. If its atmosphere contains substantially more carbon dioxide than ours, then the surface may yet be warm and wet.

Venner's team gives HD 137010b a 40% chance of orbiting within the so-called 'conservative' habitable zone. Think of this as the pessimistic, narrower option, where the greenhouse effect curtails the zone's inner edge and the loss of carbon dioxide from a planetary atmosphere marks its outer edge.

On the other hand, there's a 51% chance that HD 137010b is in the 'optimistic' habitable zone, a wider band where planetary rotation limits the greenhouse effect on the inner edge and geothermal activity can keep a planet warm on the outer edge. But there's also a 50/50 chance that HD 137010b isn't in the habitable zone at all.

So for now, HD 137010b remains a 'maybe' planet, but maybe we won't have to wait too long to find out exactly what kind of planet it really is.

The discovery of HD 137010b was described in a paper published on Jan. 27 in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

Keith Cooper is a freelance science journalist and editor in the United Kingdom, and has a degree in physics and astrophysics from the University of Manchester. He's the author of "The Contact Paradox: Challenging Our Assumptions in the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence" (Bloomsbury Sigma, 2020) and has written articles on astronomy, space, physics and astrobiology for a multitude of magazines and websites.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.