Kepler Space Telescope: The Original Exoplanet Hunter

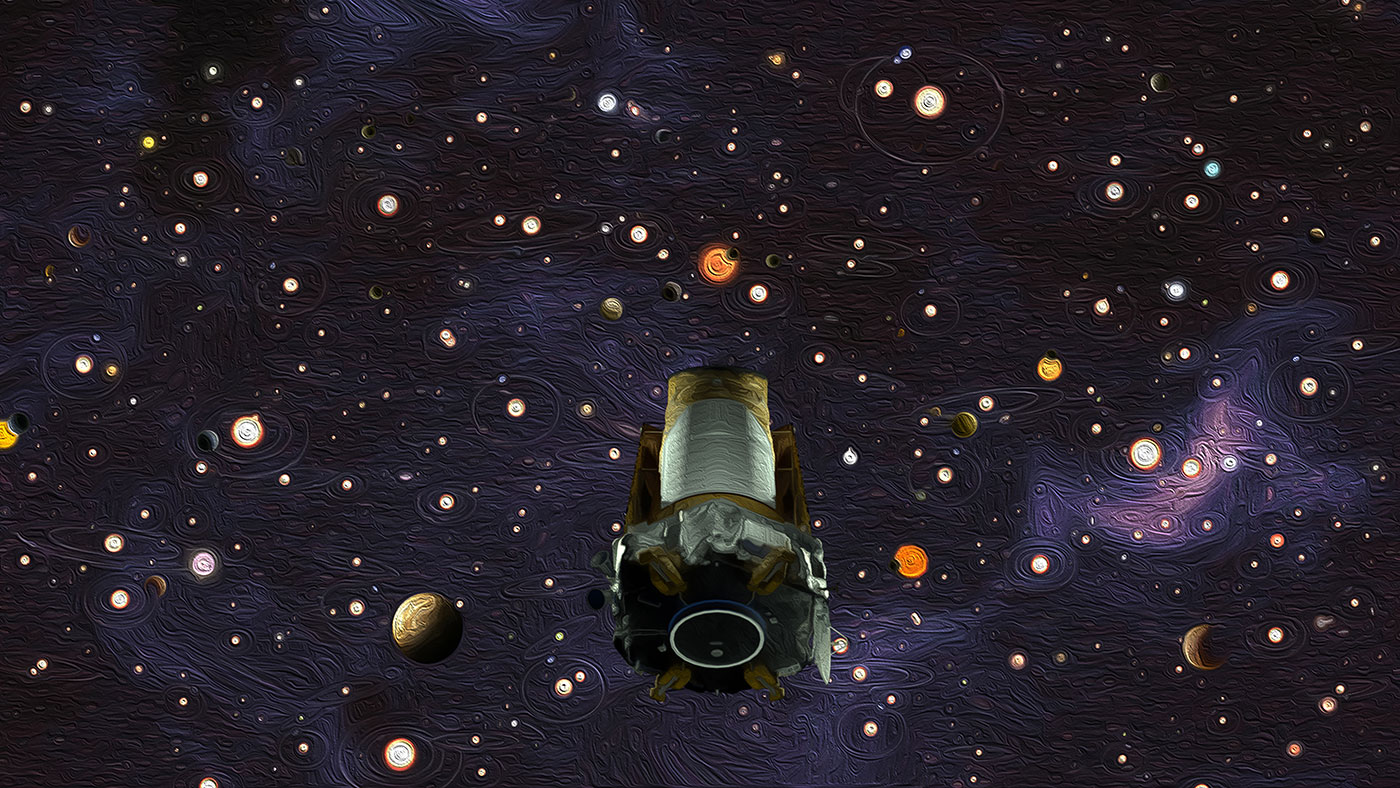

After 9 years of observations, the Kepler space telescope showed us that on average, every star has at least one planet.

NASA's Kepler Space Telescope was an observatory in space dedicated to finding planets outside our solar system, with a particular focus on finding planets that might resemble Earth. The observatory was in commission for just under nine years, from its launch in March 2009 to its decommission on Nov. 15, 2018.

Farewell, Kepler: NASA shuts down prolific planet-hunting space telescope

Since Kepler's launch, astronomers have discovered thousands of extra-solar planets, or exoplanets through this telescope alone. Most of them are planets that are between the size of Earth and Neptune (which is four times the size of Earth). Many of these planets were discovered in a region of the constellation Cygnus about the size of the palm of a hand held at arm's length, where Kepler was pointed for the first four years of its mission.

As of November 2020, Kepler had been credited with discovering 2,392 exoplanets, with 2,368 candidate planets awaiting confirmation, according to the NASA Exoplanet Archive. The mission continued well beyond its scheduled end date, although mechanical issues in 2013 forced mission managers to create a modified "K2" mission in which Kepler used the pressure of sunlight to stabilize itself, switching its view to different spots of the sky.

How Kepler got its start

Kepler was the brainchild of NASA scientist William J. Borucki, who had worked on science instruments for the Apollo program. Starting in 1983, Borucki began advocating within NASA for a mission that would search for exoplanets by watching for transits — events in which a planet passes in front of its star as seen from Earth's point of view. Borucki's concept was rejected by NASA four times, as the agency demanded various demonstrations that the mission was technologically and financially feasible. NASA finally approved the mission in 2001.

Kepler was part of NASA's Discovery program, which funds lower-cost spacecraft for exploration of the solar system. Kepler was selected at the same time as Dawn, a spacecraft that visited the small worlds Vesta and Ceres.

In a lecture at the Carl Sagan Institute at Cornell University, Borucki explained, "[Kepler] looks at over 170,000 stars simultaneously, looking for planets that cross their star and block some light. By the blocking of that light we can tell how big the planet is compared to the star, and when it repeats we can tell the orbital period. From Kepler's third law we can deduce how far the planet is from the star. And by looking at the properties of the star we can tell how hot that planet might be."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Read more: Astronomer Johannes Kepler unlocked the secrets of planetary motion

Kepler's third law, named after the astronomer Johannes Kepler (1571-1630), states that if you know the length of a planet's year (its orbital period) and the mass of its parent star, you can calculate its average distance from the star.

One of the superpowers of the Kepler space telescope is its ability to measure the brightness of a star to a tiny fraction of a percent. This precision photometry is necessary to pick up the tiny dimming caused by a planet in front of its star. For example, Jupiter passing in front of the sun blocks about 1% of the sun's light; Earth blocks less than 0.01%.

In the early years of exoplanet hunting, astronomers were best able to find huge gas giants — Jupiter's size and larger — that were lurking close to their parent star. The addition of Kepler's sensitive photometry (as well as more sophisticated planet-hunting from the ground) means that astronomers have found more "super-Earths," or planets that are just slightly larger than Earth but have a rocky surface. Kepler's finds also allow astronomers to begin grouping exoplanets into types, which helps with understanding their origins.

Primary mission

The $600 million Kepler telescope was launched in 2009 with the expectation that it would operate for a year.

In the early days, an important part of Kepler operations was eliminating false positives. Because apparent star dimming can also take place through means other than exoplanet transits (for example, due to a star's natural variability, starspots, or another star or pair of stars somewhere in the same line of sight), each candidate planet was confirmed through other telescopes, generally by measuring the gravitational "wobble" exhibited by a star in response to a revolving planet.

But Kepler's original mission was not so much to identify individual exoplanets as it was to take a census of as many stars as possible and estimate the percentage of stars that host planets.

So, as Kepler accumulated experience, statistical methods were brought into play. For example, in February 2014 astronomers pioneered a new technique called "verification by multiplicity," which distinguishes multiple-planet systems from multiple-star systems and thus finds many exoplanets at once. Through this technique, the team unveiled 715 confirmed planets in one release, making the largest batch of planets in a single announcement up to that time.

Related: Gallery: A world of Kepler planets

Kepler was approved far beyond its original mission length and was operating just fine until May 2013, when a second of its four reaction wheels or gyroscopes failed. The telescope needs at least three of these devices to stay pointed in the right direction. At the time, NASA said the telescope was still in good condition otherwise, and investigated alternate mission ideas for the hardware.

New mission

Within a few months, the agency came up with a new mission for the space telescope that it dubbed K2. The mission would use the sun's solar wind to stabilize the telescope for several months at a time. Then, about four times a year, the telescope, which is about 15 feet (4.7 meters) long and 9 feet (2.7 m) in diameter, would turn to a different field of view when the sun got too close to its sensors.

Related: NASA's ailing planet-hunting Kepler spacecraft moves closer to new mission

In July 2015, as the new mission settled into a routine, Borucki, still the principal investigator at the time, retired after 53 years of service to NASA, according to the agency.

While the pace of planetary discovery was less with the new mission, new finds continued. In January 2016, NASA announced the discovery of more than 100 new planets based on K2 observations. "This is a validation of the whole K2 program's ability to find large numbers of true, bona fide planets," Ian Crossfield, an astronomer at University of Arizona, said during the American Astronomical Society's annual meeting, during which the find was announced.

Related: NASA's Kepler comes roaring back with 100 new exoplanet finds

Kepler examined the TRAPPIST-1 system — which likely has multiple Earth-sized planets in it — between December 2016 and March 2017. That February, another team of astronomers announced more Earth-sized planets had been found. Kepler scientists then released the raw data from their TRAPPIST-1 observations for other teams to analyze, if they were interested.

In February 2018, NASA put out another release of Kepler data on 95 new planets found during the K2 mission. One of those planets was orbiting a bright star, making it an easy candidate for follow-up by a ground observatory.

Major discoveries

Thanks to Kepler, we now know how common it is for other stars to have planets.

"Essentially every star has a planet. That's a big deal, and was not appreciated before Kepler," former Kepler project scientist Nick Gautier said in a statement released when the telescope was retired.

Over the first seven years of Kepler and K2 operations, NASA issued two dozen press releases announcing newly discovered exoplanets, often in large batches.

In June 2017, came the final release of data from Kepler's primary mission. Kepler's confirmed planetary finds were boosted to 2,335. Including potential planets, the total count stood at 4,034.

Related: NASA's Kepler space telescope finds hundreds of new exoplanets, boosts total to 4,034

The K2 mission ended up lasting as long as the primary mission, and brought Kepler's total number of surveyed stars up to more than 500,000, according to a NASA press release.

Another major achievement was discovering the sheer variety of planetary systems that are out there. Planet systems can exist in compact arrangements within the confines of the equivalent of Mercury's orbit. They can even orbit around two stars, much like Tatooine in the Star Wars universe. And in an exciting find for those seeking life beyond Earth, the telescope revealed that small, rocky planets similar to Earth are more common than larger gas giants such as Jupiter.

Related: 'Alien megastructure' ruled out for some of star's weird dimming

Other weird worlds discovered by the telescope include Kepler-62e and Kepler-62f — two water worlds that likely have a global ocean, unlike Earth, which has a significant fraction of dry land. The planets are about 1,200 light-years away in the constellation Lyra and are close to the size of Earth.

Long-term Kepler observations of the star KIC 8462852, also known as "Tabby's Star," revealed a bizarre pattern of dimming and brightening. Astronomers are still trying to figure out the nature of the unusual changes in brightness, which have been attributed to anything from comets to an uneven ring of dust, and even an alien megastructure.

Related: NASA's planet-hunting Kepler tackles mystery of the Pleiades' 'seven sisters'

Kepler's great sensitivity to the changing brightness of stars was exploited for the Pleiades, a well-known cluster of stars that is only 400 light-years away and visible to the naked eye. Kepler's observations provided the best tracking of their variability yet. The telescope also provided new measurements of exploding stars and sound waves inside stars.

Mission's end

Kepler was launched with 3 gallons (12 kilograms) of hydrazine in its fuel tank. The fuel powers the thrusters that help correct drift and perform big maneuvers, including pointing to new fields of view and orienting its transmitters to Earth to downlink science data and receive commands. Because Kepler does not have a precise gauge on its fuel tank, engineers could only estimate when it was running out of fuel.

In March 2018, NASA announced that it expected the spacecraft's fuel tank to run dry in the following months. A little over seven months later, on October 30, NASA confirmed that Kepler was out of gas. Engineers sent a final "good night" command and officially decommissioned the spacecraft on Nov. 15, 2018 — coincidentally, the 388th anniversary of the death of Johannes Kepler.

Related: NASA's planet-hunting Kepler space telescope is done. What will happen to it?

Though inactive, Kepler will continue in its Earth-trailing orbit around the sun, passing through Earth's neighborhood (at a safe distance) in 2060 and again in 2117.

Kepler's role as the leading exoplanet-hunting space telescope was taken over by the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS), which was launched on April 18, 2018 and completed its primary mission on Aug. 11, 2020 before beginning an extended mission phase. While Kepler's mission was primarily statistical — to discover whether Earth-size exoplanets were common — TESS is designed to identify specific exoplanet systems that should be examined further.

Additional resources:

- Read NASA's Kepler and K2 Mission Overview.

- Check out Kepler's major discovery milestones through the years.

- Learn more about NASA's other Discovery missions.

This article was updated on Jan. 26, 2021 by Space.com Contributor Steve Fentress

Steve is a former contributor to Space.com in the coverage areas of stars, exoplanets, and constellations. He's an author, podcaster, and retired Planetarium Director at Rochester Museum & Science Center where he was employed for 28 years and responsible for content and scheduling of the venue's Planetarium astronomy shows. Other duties included adapting still and moving images, music and sound, narrating shows, and leading selection and scheduling of all film and laser shows. His book, Sky to Space: Astronomy Beyond the Basics with Comparisons, Ratios and Proportions was published in 2017.