Why don't more Tatooine-like exoplanets exist in our Milky Way galaxy? Astronomers might have an answer

Albert Einstein's theory of general relativity strikes again.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

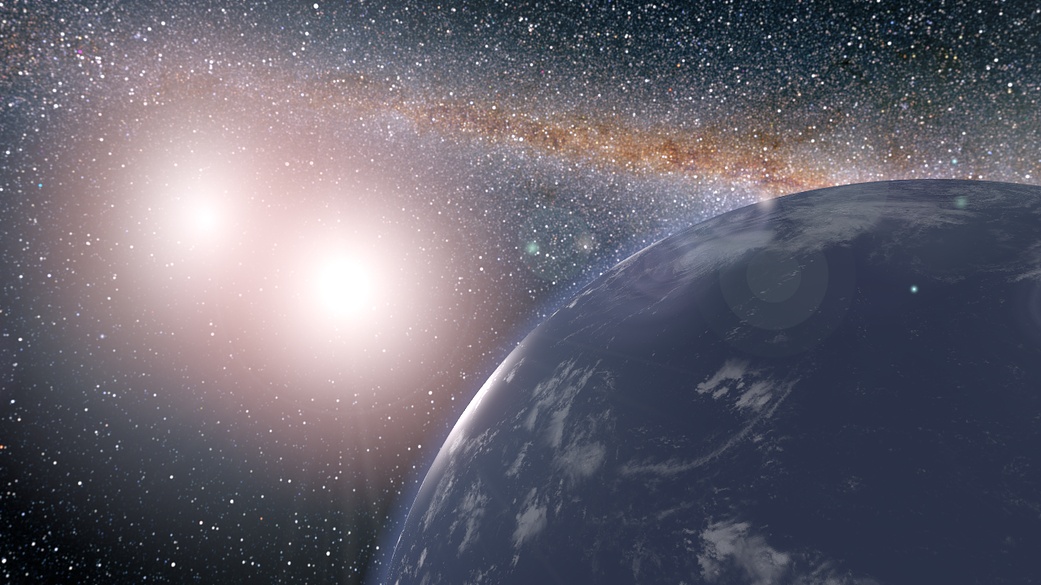

It's one of the most instantly recognizable scenes in cinematic history: Luke Skywalker gazes at a double sunset to the haunting melody of a mournful French horn. And while "Star Wars" may take place in a galaxy far, far away, planets orbiting binary stars actually do exist in the Milky Way. Yet mysteriously, there are not as many as scientists expect — and new research might explain why.

Of the thousands of single-star systems in our galaxy, around 10% are known to have planets. Scientists thus expected about 10% of the 3,000 known binary star systems in our galaxy to have them, too. But of the more than 6,000 confirmed exoplanets in the Milky Way, just 14 confirmed planets have been found around pairs of stars.

Researchers from the University of California, Berkeley, and the American University of Beirut suggest the culprit might be Albert Einstein's theory of general relativity.

Article continues belowIn most binary star systems, two stars orbit each other in elliptical paths. A planet caught in that dance feels gravitational forces from both stars, causing its orbital orientation to slowly rotate in a process known as precession. Meanwhile, the binary stars' own orbits also precess due the rules of general relativity. As time progresses, tidal forces between the stars can draw them closer, accelerating their precession and causing an orbiting planet's precession to slow.

When the precession rates align, the planet's orbit becomes highly stretched. According to lead author Mohammad Farhat of the University of California, Berkeley, this resonance can destabilize the planet's path. "Either the planet swings too close to the stars and is torn apart, or its orbit is so perturbed that it's ejected from the system," he said in a statement.

The team's models suggest that in tight binaries — those with orbital periods of a week or less — such disruptions are common. These systems also happen to be the ones most likely to be monitored by missions like NASA's Kepler and TESS, which detect planets by watching for starlight dimming as a planet passes in front of them. That could partly explain the surprisingly low number of circumbinary planets in observational data.

Ultimately, there might be hundreds or thousands of Tatooines in the Milky Way — we just aren't sure how to look for them yet.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The team's findings were published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters on December 8, 2025.

Space.com contributing writer Stefanie Waldek is a self-taught space nerd and aviation geek who is passionate about all things spaceflight and astronomy. With a background in travel and design journalism, as well as a Bachelor of Arts degree from New York University, she specializes in the budding space tourism industry and Earth-based astrotourism. In her free time, you can find her watching rocket launches or looking up at the stars, wondering what is out there. Learn more about her work at www.stefaniewaldek.com.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.