Hubble telescope discovers rare galaxy that is 99% dark matter

"This is the first galaxy detected solely through its globular cluster population."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

All galaxies are dominated by dark matter, an invisible "stuff" that outweighs all of the matter comprising stars, planets, and moons by around five to one. But in some galaxies, dark matter takes this domination to the extreme. Using the Hubble Space Telescope along with the Euclid Space Telescope, astronomers have discovered what seems to be one of the most heavily dark-matter-dominated galaxies ever seen.

This "dark galaxy," officially designated CDG-2, is located around 245 million light-years away. Unlike regular galaxies, which are bright and prominent even across vast cosmic distances, dark galaxies like CDG-2 are faint, nearly invisible and ghost-like thanks to a sparse smattering of stars and their huge quantity of dark matter.

The team behind the discovery of this galaxy found that, unlike standard galaxies, in which dark matter outweighs ordinary matter by a ratio of five to one, dark matter accounts for a staggering 99% of the mass of CDG-2.

Dark matter is effectively invisible, because unlike protons, neutrons, and electrons — the particles that comprise everyday matter — whatever composes dark matter doesn't interact with electromagnetic radiation, that's "light" to you and me. Scientists have been able to determine that galaxies are ruled by dark matter, with dense central cores and halos that extend far beyond visible gas and dust, due to the fact that dark matter does interact with gravity.

This gravitational influence then influences visible matter and light, a knock-on effect which astronomers can see. Even so, dark galaxies are extremely tough to detect.

The discovery of CDG-2 began when a team of astronomers investigated tight groupings of stars called globular clusters, which can often indicate the presence of a hidden population of dim stars in their vicinity. This led to the confirmation of ten faint low-brightness galaxies and two dark galaxy candidates.

To confirm the existence of one of these dark galaxies, the researchers turned to Hubble, Euclid, and the Subaru Telescope in Hawaii.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

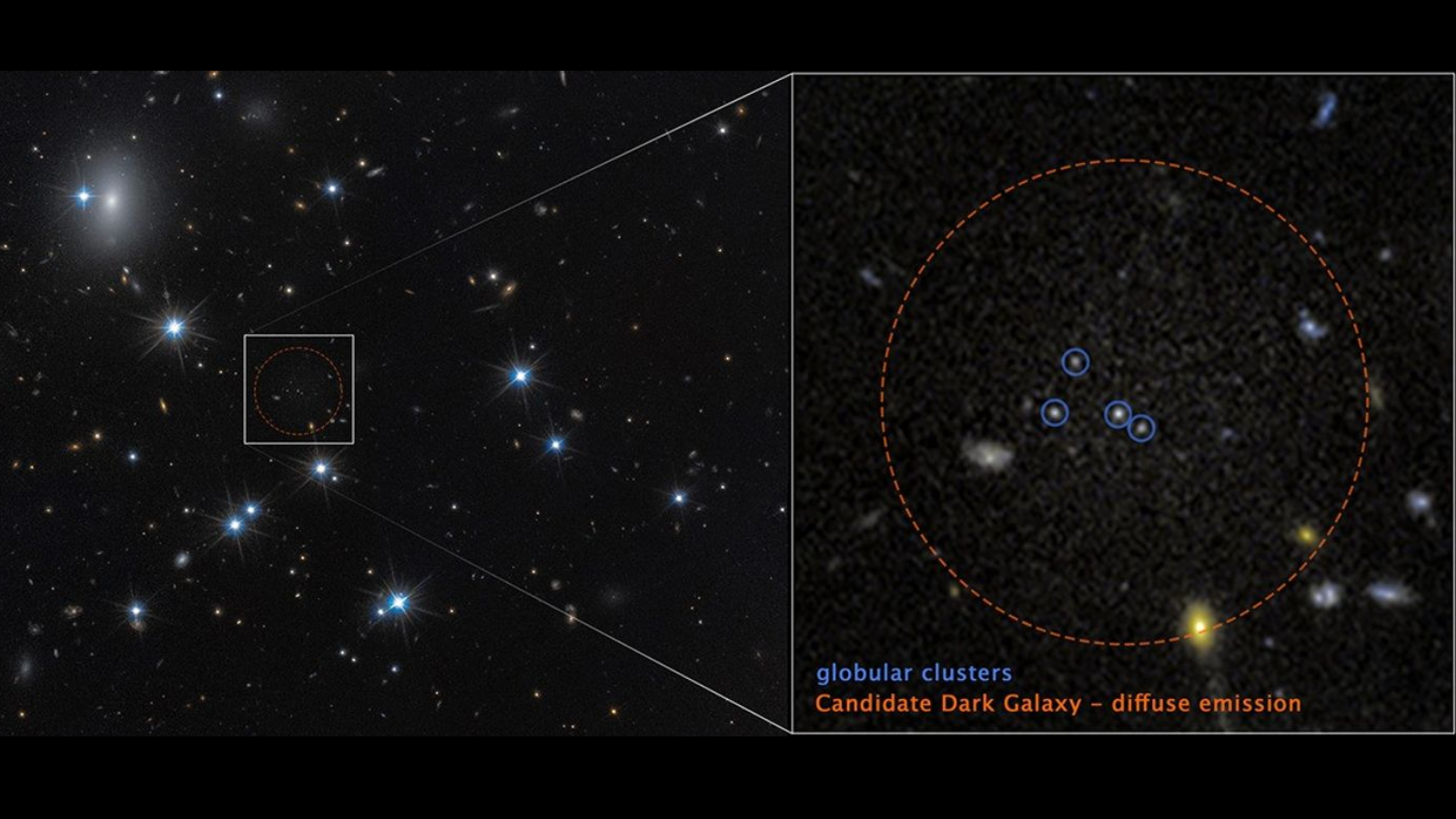

Hubble data confirmed a tight grouping of four globular clusters in the Perseus galaxy cluster, located around 300 million light-years away. Further observations from Hubble, along with data from Euclid and Subaru, revealed a faint glow around these globular clusters, which served as evidence of a hidden, near-invisible galaxy lurking behind these globular clusters. CDG-2 had revealed itself.

"This is the first galaxy detected solely through its globular cluster population," team leader David Li of the University of Toronto, Canada, said in a statement. "Under conservative assumptions, the four clusters represent the entire globular cluster population of CDG-2."

Li and colleagues performed a deeper analysis of CDG-2, finding that it has a brightness equivalent to that of around 6 million sun-like stars. They determined that around 16% of this brightness was accounted for by the overlying globular clusters. The normal matter in this dark galaxy is thought to have enabled star formation in its past, but the team theorizes these stellar bodies have been stripped away by gravitational interactions with other galaxies. The globular clusters used to detect CDG-2 were able to withstand this gravitational interference due to how densely packed with stars they are, leaving them the only tracers of a now ghostly galaxy.

The team's results were published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. whose articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space, Newsweek and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University. Follow him on Twitter @sciencef1rst.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.