Does dark matter actually exist? New theory says it could be gravity behaving strangely

"It highlights gravity's possible hidden complexity and invites a reevaluation of where dark matter effects originate."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

New research suggests that dark matter, the universe's most puzzling and mysterious substance, may not exist. But removing dark matter from our cosmological models could hinge on the possibility that gravity behaves differently on very large scales, one scientist says.

Dark matter has been a thorn in the side of physicists because, despite outweighing ordinary matter by a ratio of 5 to 1, it remains effectively invisible. That's because it doesn't interact with light, or more technically, electromagnetic radiation. Because the particles that comprise the atoms that make up stars, planets, moons, living things, and everything we see around us, do interact with light, scientists have been searching for particles that could make up dark matter. However, this addition to particle physics, which has thus far eluded all attempts to uncover it, isn't needed if we are wrong about how gravity behaves on galactic scales. At least, that is what Naman Kumar of the Indian Institute of Technology suggests.

"The mystery of dark matter — unseen, pervasive, and essential in standard cosmology — has loomed over physics for decades," Kumar wrote for Phys.org. "In new research, I explore a different possibility: Rather than postulating new particles, I propose that perhaps gravity itself behaves differently on the largest scales."

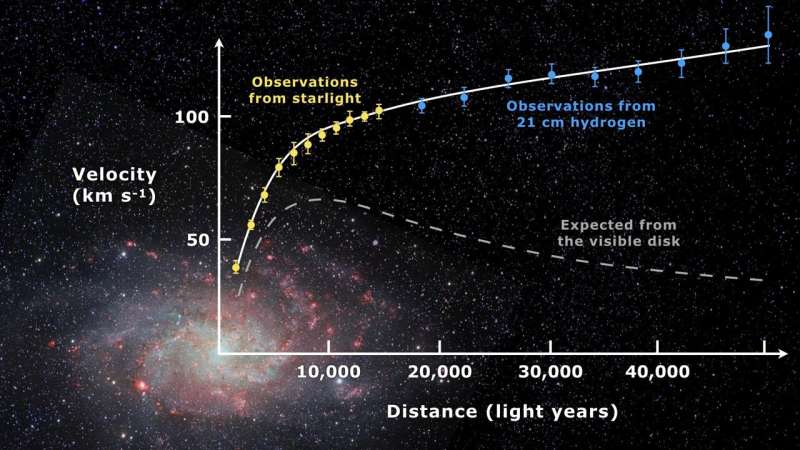

Article continues belowThe only reason that scientists have inferred the presence of dark matter is that this strange matter does interact with gravity. In fact, the first hint of dark matter came from the fact that galaxies were observed to be spinning so rapidly that if the gravity of their visible matter was the only force acting to keep them together, they would have flown apart long ago.

Another line of evidence comes from a phenomenon called "gravitational lensing," which occurs when the usually straight path of light is curved by a dent in the fabric of space generated by objects of great mass. This deflection has been found to be too extreme to be accounted for by the visible matter in lensing galaxies. Hence, physicists have inferred that galaxies are embedded with vast haloes of dark matter that extend far beyond their haloes of stars.

The fact that the only evidence for dark matter comes from its gravitational effect on space and by extension everyday or "baryonic" matter explains why a modified theory of gravity could do away with the need for dark matter to exist.

Don't be a square

To investigate this, Kumar looked at gravity through the lens of quantum field theory and at very small scales equivalent to the wavelength of infrared light, a so-called "infrared running scheme." This involved not assuming that Newton's gravitational constant, or "Big G," is allowed to change or "run" at different length scales.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"What emerged is a compelling theoretical case for a scenario in which gravity's effective strength subtly shifts over galactic distances," Kumar wrote.

Gravity is just one example in physics of an "inverse square law" of 1/r^2, meaning that its strength falls off by the square of the distance from a source; when the distance from a gravitating body doubles, then its gravity becomes four times weaker. If the distance is tripled, then the gravitational influence becomes nine times weaker.

Considering his infrared running scheme, Kumar found a gravitational potential that deviates from the usual inverse force law, leading to a long-range force of 1/r. This can lead to the type of rotation seen for galaxies that is currently attributed to dark matter halos.

"These results suggest that the infrared running scenario could account for galaxy rotation without invoking a dominant cold dark matter component," Kumar explained.

As you might expect, because dark matter is considered to account for 85% of the matter in the universe, it stands to reason that removing it from our models of the cosmos has significant implications for understanding how the universe evolved and continues to evolve. However, Kumar's model may fit well with current expectations and observations.

"In the early universe — at the time of the cosmic microwave background and during structure formation — any change in gravity must be small enough to avoid conflict with precision cosmological measurements," Kumar wrote. "Within the infrared running framework, corrections grow slowly with scale and time, preserving agreement with early-universe constraints while becoming relevant only at later epochs and large scales."

The next step for Kumar's theory of infrared-running gravity will be to see how it compares to measurements of gravitational lensing and the gathering of galaxy clusters, currently thought to occur around a framework of dark matter.

"My work opens a path toward understanding dark matter phenomena not as missing particles, but as a subtle feature of gravitation itself — a deep consequence of scale dependence in a quantum field theory of gravity," Kumar concluded. "Although this approach does not yet fully replace dark matter in the cosmological standard model — especially in explaining detailed structure formation and lensing data — it highlights gravity's possible hidden complexity and invites a reevaluation of where dark matter effects originate."

Kumar's research was published in the journal Physical Review Letters B.

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. whose articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space, Newsweek and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University. Follow him on Twitter @sciencef1rst.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.