Astronomers witness vanishing star collapse into a black hole in Andromeda galaxy

"This is essentially as close as we can get to seeing the death of a massive star."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Astronomers may have witnessed the birth of a brand-new black hole in our neighboring galaxy, offering one of the clearest glimpses yet of how some stars quietly collapse into these cosmic abysses without the usual fireworks of an explosion.

While scouring archival data from NASA's NEOWISE mission, a team led by Columbia University astronomer Kishalay De discovered that one of the brightest stars in the Andromeda Galaxy mysteriously brightened over a decade ago, faded dramatically and then vanished from view. The star, labeled M31-2014-DS1, lay about 2.5 million light-years from Earth and weighed just 13 times the mass of our sun — relatively lightweight by typical black hole-forming standards, according to De and colleagues' research.

"Observations like these are starting to finally change this long-held paradigm that it's only the very massive stars that turn into black holes," De told Space.com.

Article continues below

If this detection holds up, he added, "then it really means that there are many more black holes out there than what we've anticipated so far."

Before it vanished, the star shone roughly 100,000 times brighter than our sun. De likened its prominence to Betelgeuse, a well-studied red supergiant that marks the right shoulder of the constellation Orion.

If Betelgeuse were to fade from the sky over a few years, De said, "that would really be shocking and disturbing for us here on Earth, because suddenly Orion wouldn't look the way it does."

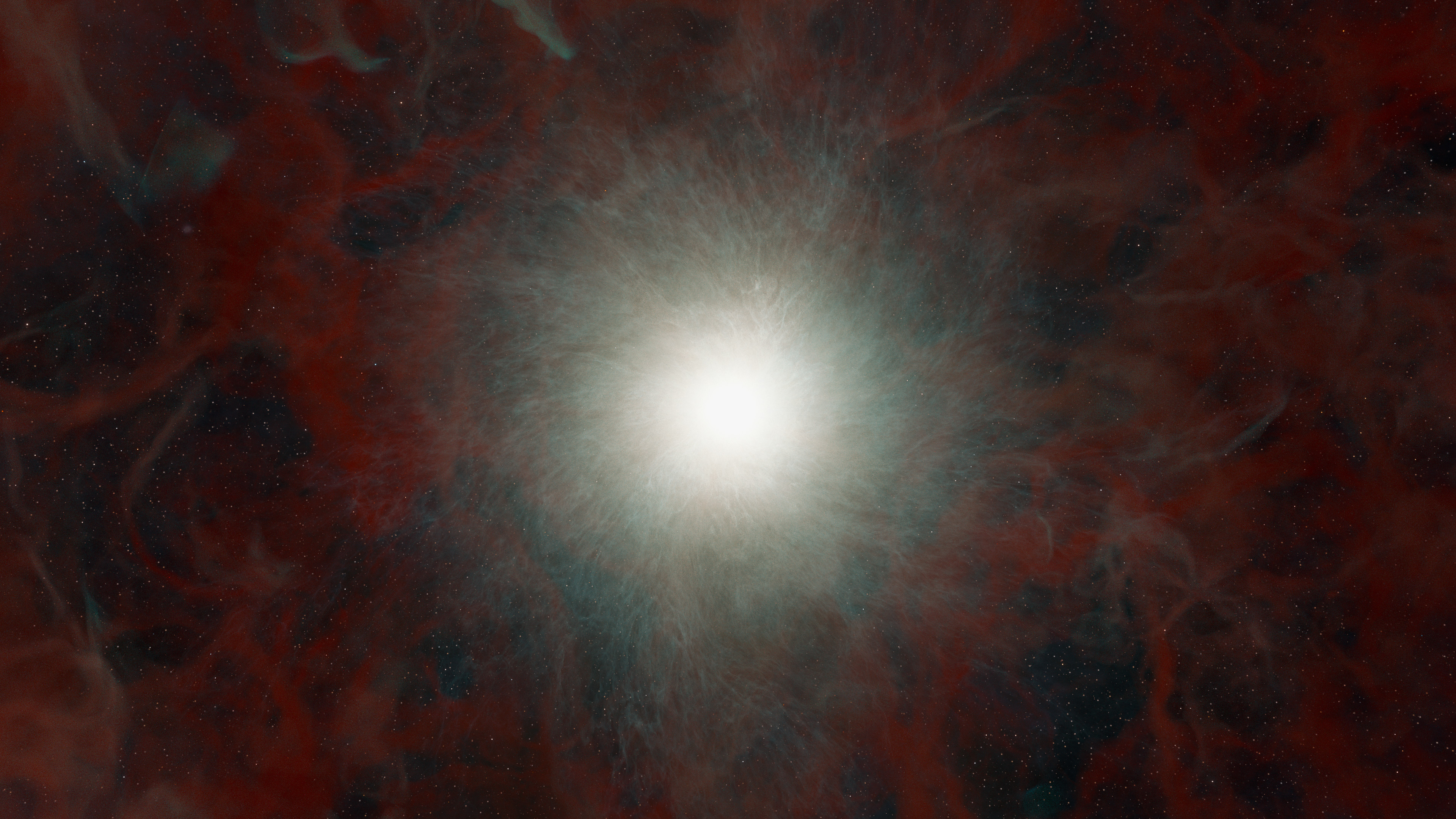

De and his team first noticed M31-2014-DS1's strange behavior in data from the NEOWISE mission. Around 2014, the team's new paper reports, the star brightened in infrared light, then began dimming sharply in 2016, and by 2023 had effectively vanished — fading to roughly one ten-thousandth of its original brightness.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

De said he was sitting in front of a computer at the Keck Observatory in Hawaii in 2023, collecting follow-up observations of the star when he noticed something did not add up.

"I remember the moment when we pointed the telescope towards this star — except the star was not there at all," he recalled. Additional observations from the Hubble Space Telescope and other ground-based observatories confirmed that the star was truly gone. "That's when it clicked," De said. "Stars that are this bright, this massive, do not just randomly disappear into darkness."

According to a leading theory, black holes form when massive stars exhaust their nuclear fuel, triggering an explosive supernova that blasts the star's outer layers into space that leaves behind either a dense neutron star or a black hole. M31-2014-DS1, however, appears to have formed a black hole without any such fireworks.

"Ten years ago, if someone said a 13 solar-mass star would turn into a black hole, nobody would believe that," De said. "It was completely outside what was considered the norm."

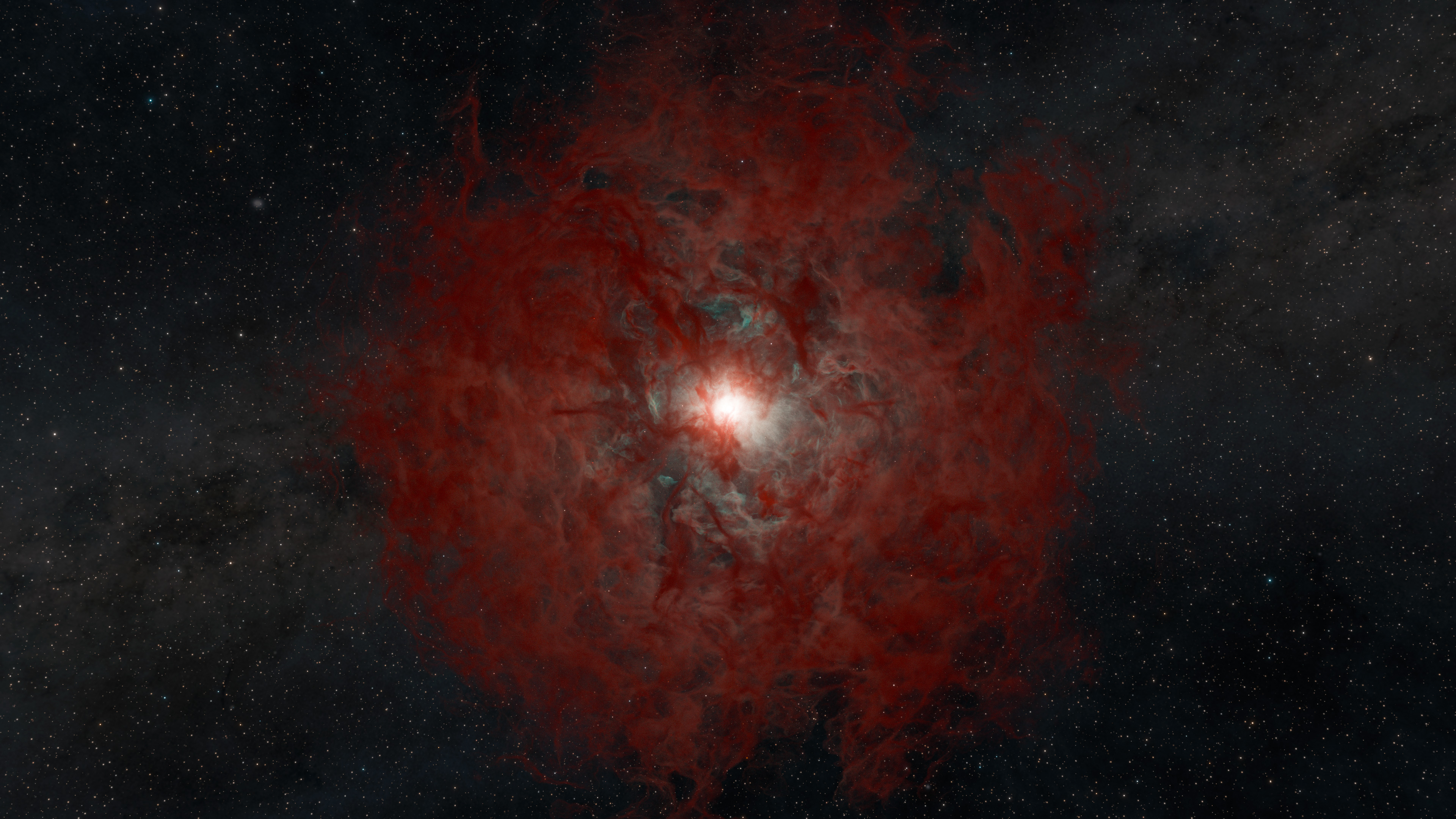

De and his colleagues suspect M31-2014-DS1's small, densely packed core collapsed into a black hole in a matter of hours. What astronomers can still see is not the star itself, but a faint glow in infrared light produced by leftover dust and gas swirling around the newborn black hole.

That material is moving too fast to fall straight in, said De, instead forming a rotating disk that slowly feeds the black hole over time — much like water swirling around a bathtub drain before finally slipping down. Over the next few decades, the infrared signal is expected to fade steadily as more of the remaining debris spirals inward and disappears.

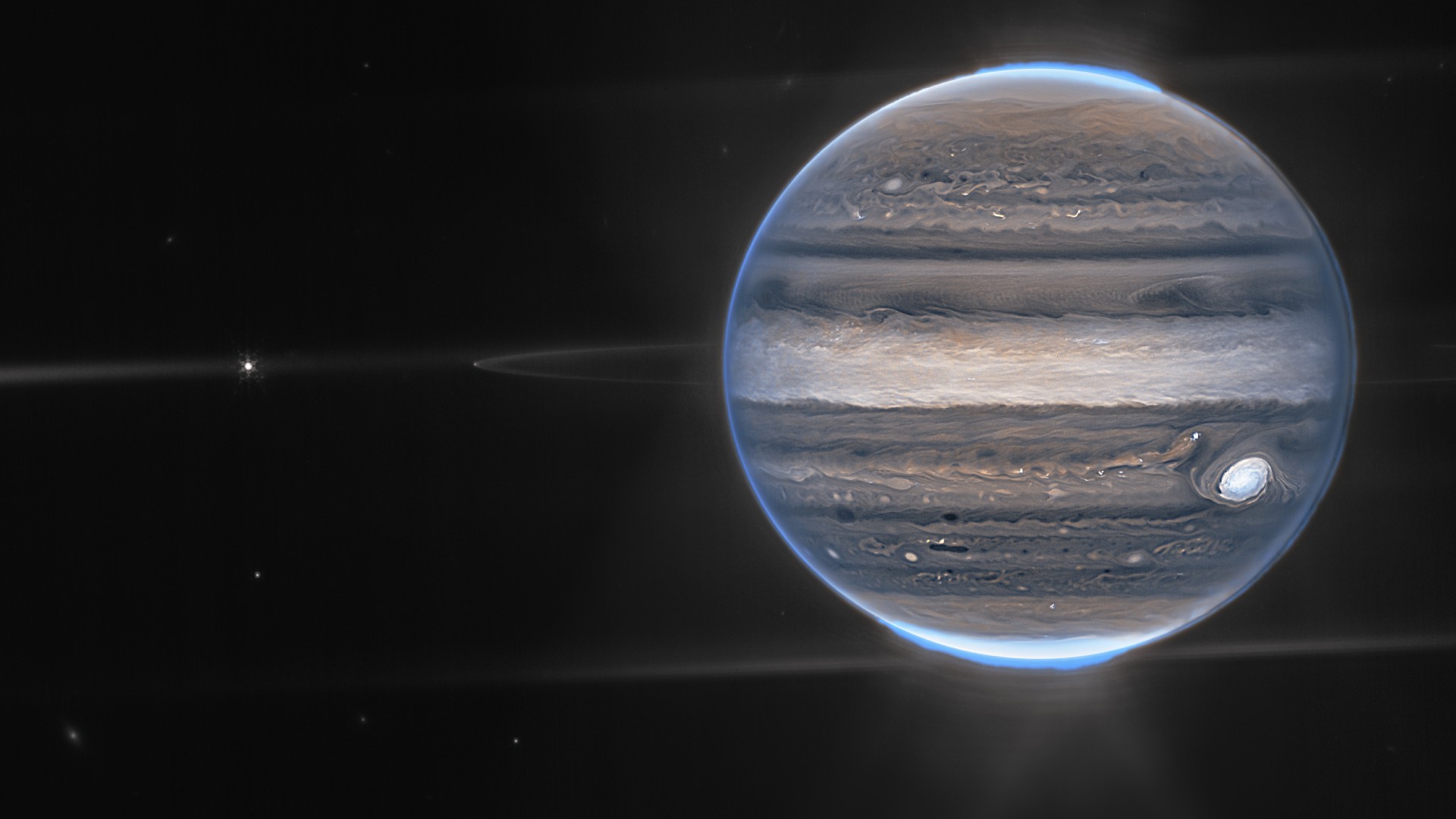

Because the Andromeda Galaxy is relatively close in cosmic terms, the fading debris should remain visible to powerful observatories such as the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), De said. But directly imaging the black hole itself — as the Event Horizon Telescope has done for much larger black holes — is not possible in this case, at least with current technology, given the object's small size.

Last year, the team gathered additional data from JWST, whose powerful infrared vision revealed that the black hole remains heavily shrouded in the star's outer material, according to a preprint posted on arXiv on Jan. 9.

To further test their conclusion, the researchers also used NASA's Chandra X-ray Observatory to search for high-energy radiation expected from hot gas near the black hole. No X-rays were detected, but that was expected, De said, because the surrounding gas is currently too dense to allow the radiation to escape into space.

Over time, as more material falls inward and the environment gradually clears, De expects telescopes may eventually detect X-rays "emerging from inside that mess that exists right now," potentially revealing the black hole more directly.

The findings also offer a new blueprint for discovering similar events, the researchers say. Instead of painstakingly monitoring billions of stars in nearby galaxies to see which ones suddenly vanish, astronomers can search for brief infrared flare-ups — possible warning signs that a star is about to undergo a quiet collapse like M31-2014-DS1.

"This is essentially as close as we can get to seeing the death of a massive star," said De. "In the end, I think it teaches us a lot more about stellar physics by not exploding."

A study about this star is reported in a paper published Thursday (Feb. 12) in journal Science.

Sharmila Kuthunur is an independent space journalist based in Bengaluru, India. Her work has also appeared in Scientific American, Science, Astronomy and Live Science, among other publications. She holds a master's degree in journalism from Northeastern University in Boston.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.