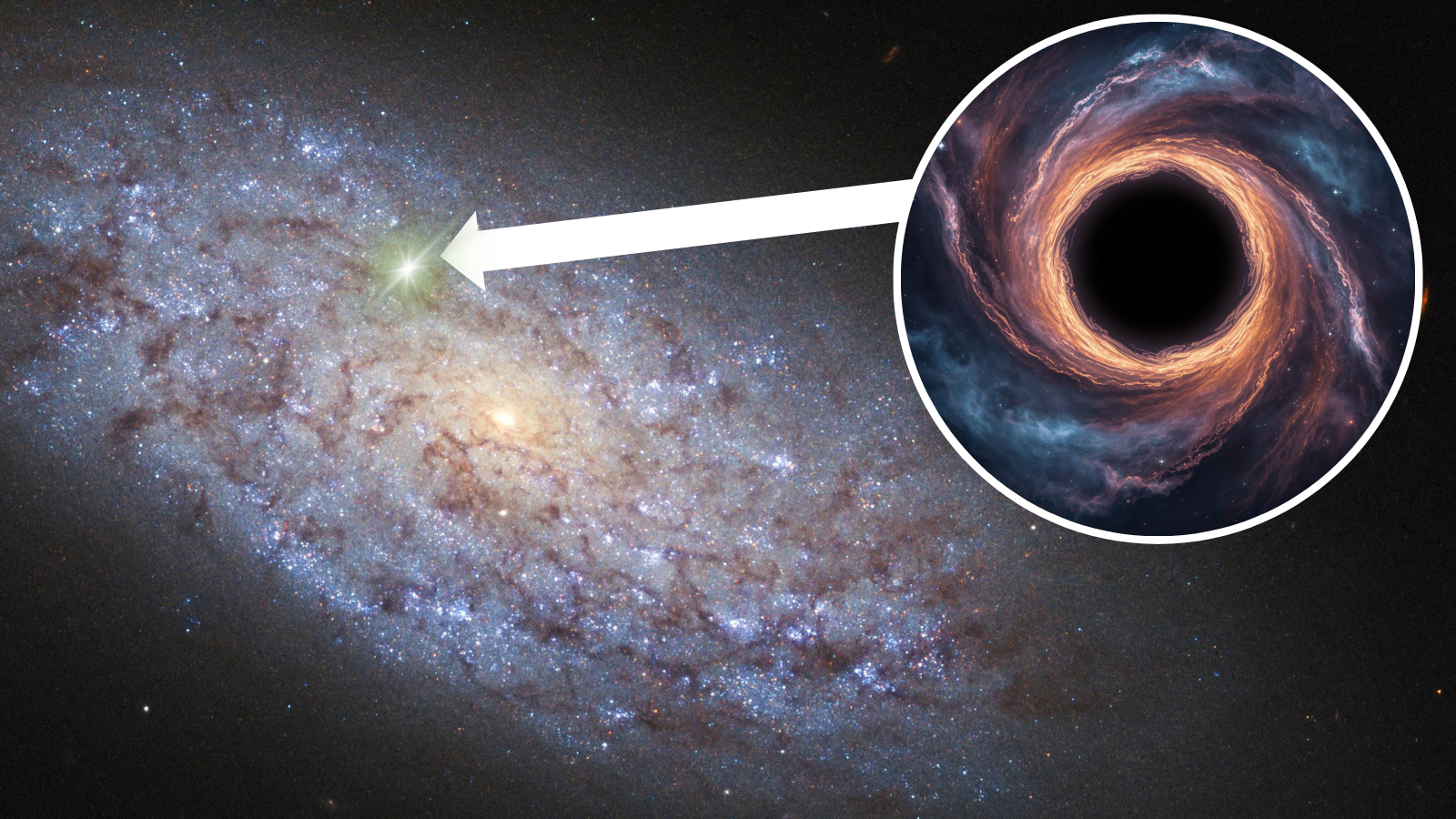

Hubble and Chandra space telescopes hunt for rogue black holes wandering through dwarf galaxies

The investigation could solve the mystery of how supermassive black holes grew so large in the early universe.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Using NASA's Hubble Space Telescope and Chandra X-ray Observatory, astronomers have hunted for "wandering" black holes drifting through dwarf galaxies. The discovery of these rogue black holes in such small galaxies could provide a "fossil record" that helps to explain how supermassive black holes grew to masses of millions or even billions of times that of the sun.

Supermassive black holes are found at the heart of all large galaxies, and the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) has increasingly been discovering these cosmic titans already in place when the cosmos was less than 1 billion years old. That is problematic because the merger and feeding processes that are thought to explain supermassive black hole growth should take over 1 billion years to reach fruition. One possible explanation for this is that the process that spawns supermassive black holes may kick off with so-called "black hole seeds" that give a head start to these growth processes. These seeds, classified as either "heavy" or "light," have proved elusive in galaxies in the early universe.

However, models of these black hole seeds predict that their signatures should be visible in dwarf galaxies in the local universe with total stellar masses of billions of times that of the sun. These dwarf galaxies provide a unique laboratory for studying black hole formation and early evolution, thanks to their relatively quiet merger histories compared to those of massive galaxies. This means they can provide a "fossil record" of the original black hole seeds via their non-central intermediate black holes.

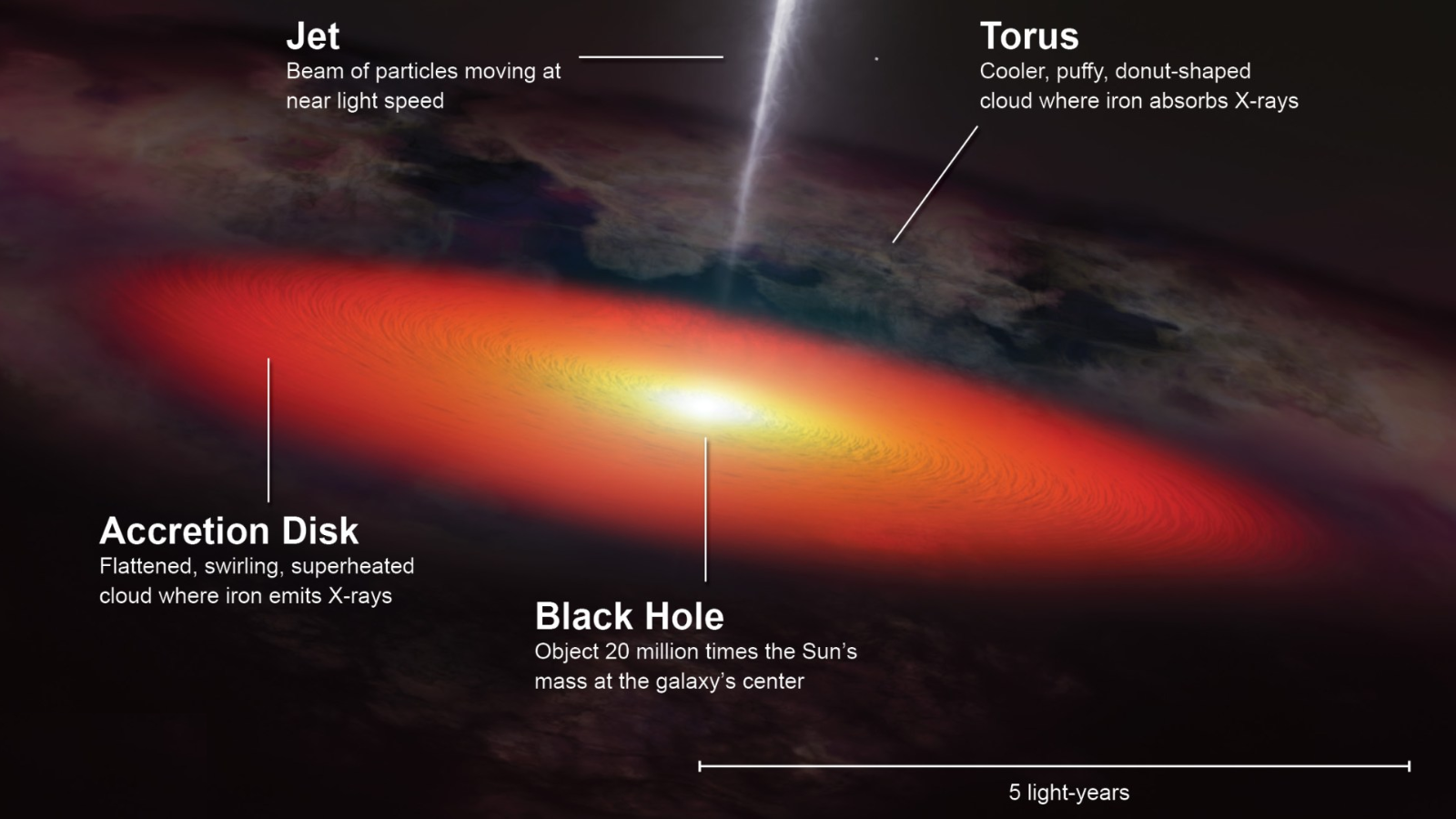

Article continues belowIn massive galaxies, central supermassive black holes can be quiet, like the Milky Way's supermassive black hole Sagittarius A* (Sgr A*), or they can be ravenously feeding on surrounding gas and dust, creating a violent and turbulent environment which astronomers call an Active Galactic Nucleus (AGN). These AGNs are bright, emitting light across the electromagnetic spectrum.

The team behind this investigation points out that the vast majority of black holes found in dwarf galaxies are accreting (gaining material and mass) and have been identified as dwelling in AGNs.

"Compared to more massive galaxies, dwarf galaxies can have lower central stellar densities and more irregularly shaped potential wells," team leader Megan R. Sturm of Montana State University told Space.com. "As a result, if a black hole forms in the outer reaches of its host galaxy, it is unlikely to ever spiral down into the center. Some researchers have even predicted that approximately half of all black holes in dwarf galaxies are wandering.

"If this is the case, all-sky surveys pointed at the centers of galaxies may simply be missing a large population of dwarf galaxies hosting massive black holes. This has important implications for black hole fraction in this mass range and, therefore, black hole formation through seeding."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Seeing off-center AGNs in a different light

The problem with detecting wandering black holes in these small galaxies is the fact that these dwarf galaxy AGNs have to be distinguished from other radiation sources, such as regions of intense star formation or "starbursts," and from supernova explosions. This can be done by investigating these regions in several different wavelengths of light.

"Observing massive black holes in the dwarf regime can be a complicated process. Since the maximum luminosity of an AGN is proportional to its mass, AGNs in dwarf galaxies are generally dimmer than their higher mass counterparts," Sturm said. "Additionally, low-luminosity/ low-mass AGNs can lack a traditional broad line region or have broad lines that are weak and hard to detect. This makes them both harder to see and easier to confuse with other stellar objects or star-formation-related processes."

This team used Chandra and Hubble to study 12 dwarf galaxies in which AGNs had previously been detected in radio waves. Eight of these AGNs appeared to be offset from the centers of their dwarf galaxy-hosts, or "non-nuclear," indicating they could harbor wandering black holes.

"Generally, supermassive black holes reside in the nucleus of massive galaxies. However, eight of the dwarf galaxies in our sample displayed compact radio emission originating from outside of the optical nucleus of the galaxy, offset by around one to two kiloparsecs [one kiloparsec is around 3,262 light-years] and in some cases outside of the host galaxy entirely," Sturm said. "These are potentially 'wandering' black hole candidates. While these wandering AGN candidates had been observed at radio frequencies, obtaining AGN-like observations at optical or X-ray wavelengths would confirm the presence of an AGN."

Sturm explained that she and her colleagues were able to detect one of these sources, designated ID 64, in optical light with Hubble and in X-rays with Chandra. However, this revealed that it is actually a much more distant AGN that simply aligns with this dwarf galaxy from our perspective.

"Seven galaxies in our sample do not have significantly detected optical/X-ray counterparts. However, it remains a possibility that these are wandering black holes that are either isolated or residing within globular or nuclear star clusters that are simply below our Hubble detection limits," she continued. "It also remains a possibility that they are background, high-redshift interlopers that happen to overlap with our galaxies in the sky, such as the case for ID 64."

Determining if these seven galaxies do indeed host wandering black holes or if these radio signals are the result of more distant AGNs could involve enlisting the help of the JWST, the $10 billion space telescope sibling of Hubble.

"Identifying the origin of the off-nuclear radio sources for the remaining seven wandering black hole candidates may be possible with the exquisite capabilities of the JWST," Sturm said. "With higher resolution, JWST could potentially observe the source of the compact radio emission, whether it be the core of a disrupted dwarf galaxy/star cluster within the host galaxy or a background, high-redshift galaxy."

The team's results are published in the Astrophysical Journal.

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. whose articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space, Newsweek and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University. Follow him on Twitter @sciencef1rst.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.