NASA X-ray spacecraft stares into the 'eye of the storm' swirling around supermassive black holes

"Before XRISM, it was like we could see a picture of the storm. Now we can measure the speed of the cyclone."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Scientists have dived deeper into the "eye of the storm" swirling around supermassive black holes than ever before. This unprecedented investigation of the turbulent and violent conditions around these cosmic titans, including the first black hole ever imaged by humanity, was possible thanks to the joint Japanese Aerospace Agency (JAXA)/ NASA X-Ray Imaging and Spectroscopy Mission (XRISM).

Using XRISM, astronomers have seen samples of supermassive black holes influencing the surrounding gas in prior X-ray images, but these were lacking as static images of an incredibly dynamic process. By measuring the energy of X-rays coming from hot gas, XRISM presents a much more dynamic picture of black hole influence than has been available before.

"It's as though each supermassive black hole sits in the 'eye of its own storm.' Before XRISM, it was like we could see a picture of the storm. Now we can measure the speed of the cyclone," team member Annie Heinrich of the University of Chicago said in a statement. "For the first time, we can directly measure the kinetic energy of the gas stirred by the black hole."

Crucial to this study, released at the end of Jan 2026 in Nature, was XRISM, which was launched in 2023. XRISM, operated in partnership with the European Space Agency (ESA), has the ability to track the chemical signature of blisteringly hot gas around supermassive black holes, determining its motion.

"XRISM allows us to unambiguously distinguish gas motions powered by the black hole from those driven by other cosmic processes, which has previously been impossible to do," team co-leader Congyao Zhang of Masaryk University said.

Supermassive black holes are messy eaters

Supermassive black holes with masses of millions or even billions of times that of the sun are thought to sit at the heart of all galaxies. Their immense gravitational influence churns gas, dust, and even proximate stars around them, thus exerting a tremendous influence on their host galaxies.

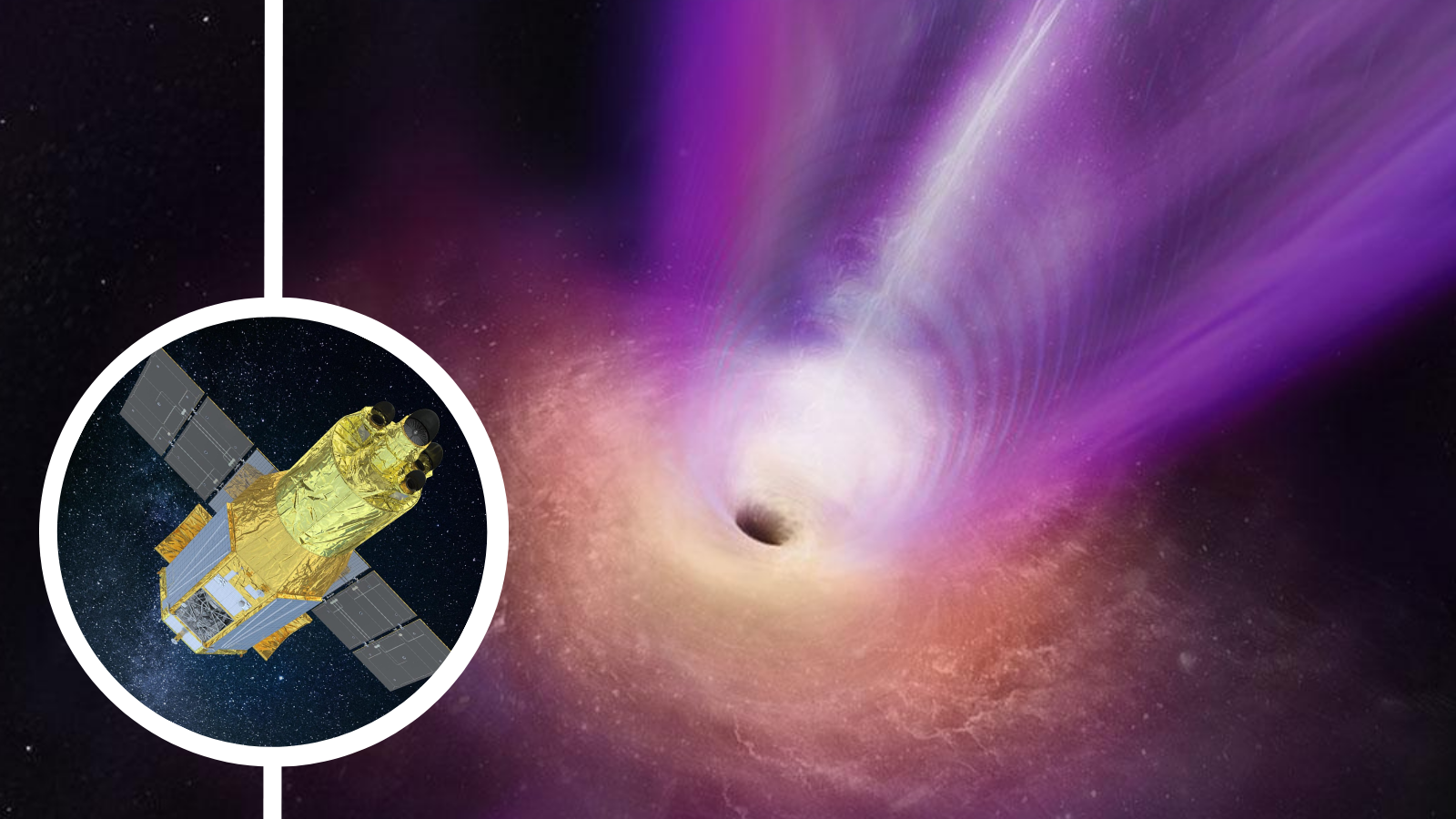

Supermassive black holes are often surrounded by vast amounts of gas and dust swirling around them in flattened clouds called accretion disks. These disks gradually feed matter to the central black hole, but a great deal of this matter is channelled to the poles of the black hole by powerful magnetic fields, where these particles are accelerated to near light-speed and blasted out as twin jets.

The fact that supermassive black holes are such messy eaters means they don't just churn gas in their vicinity, but also inject vast amounts of energy into their surroundings. This influence stretches far beyond the immediate vicinity of the supermassive black hole, reaching out for hundreds of thousands of light-years. This can influence galaxies in a variety of ways, including "killing" active star formation by forcing out gas, which serves as the building blocks for new stellar objects. Thus, understanding the impact of black holes on their home galaxies is vital for understanding galactic evolution.

Investigations such as this one are crucial to understanding the complete picture of this influence.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

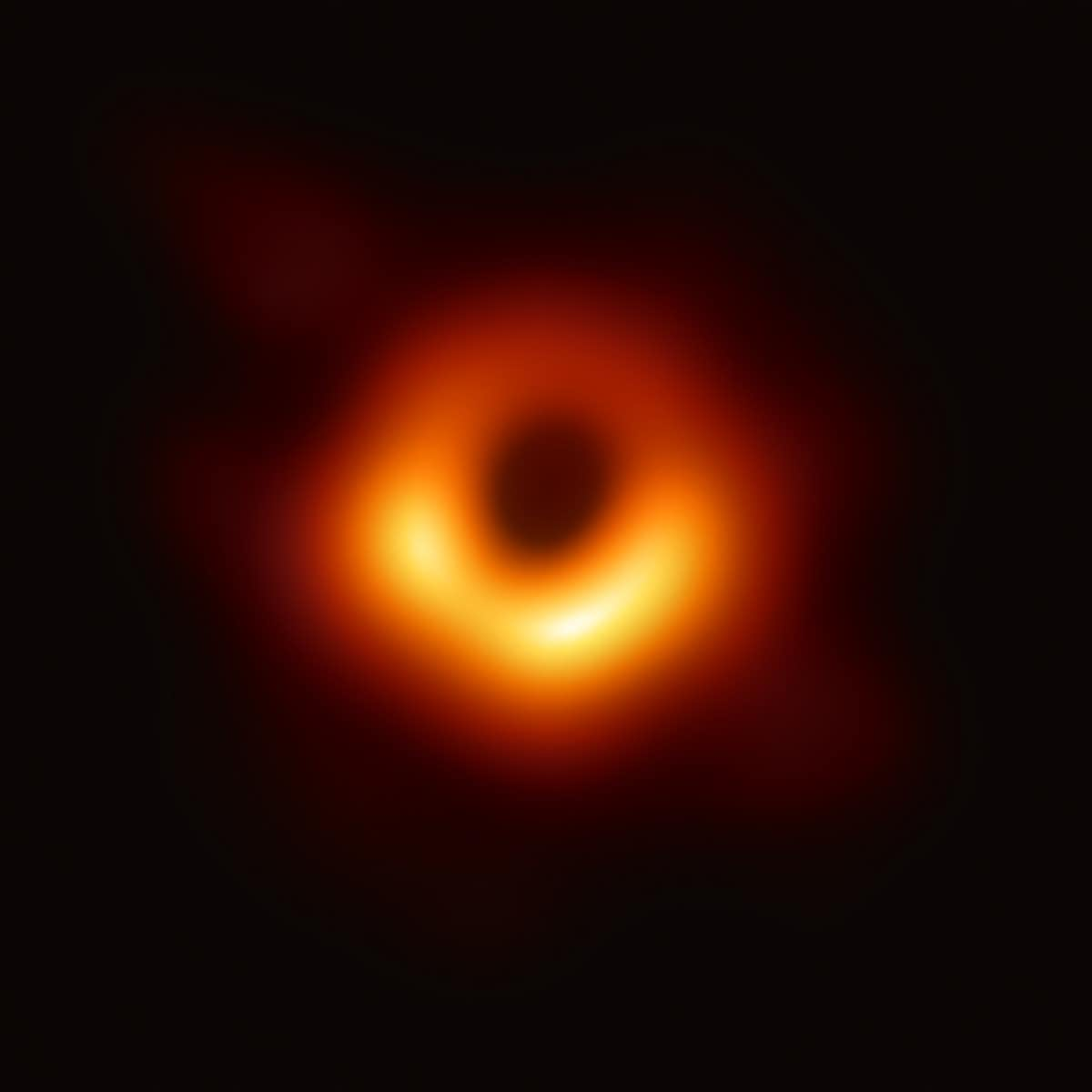

One of the supermassive black holes investigated by this team will be very familiar to astronomy fans. In 2019, the general public learned that M87*, located in the galaxy Messier 87 (M87), which itself sits in the Virgo Cluster, had become the first black hole to be imaged by humanity thanks to the Event Horizon Telescope (EHT).

In this recent study, XRISM zoomed into a relatively small region around M87*, discovering the strongest turbulence ever seen in a galaxy cluster, even more violent than the conditions generated when galaxy clusters collide and merge.

"The velocities are high closest to the black hole, and drop off very quickly further away," team member and University of Chicago researcher Hannah McCall said. "The fastest motions are likely due to a combination of eddies of turbulence and a shockwave of outflowing gas, both a product of the black hole."

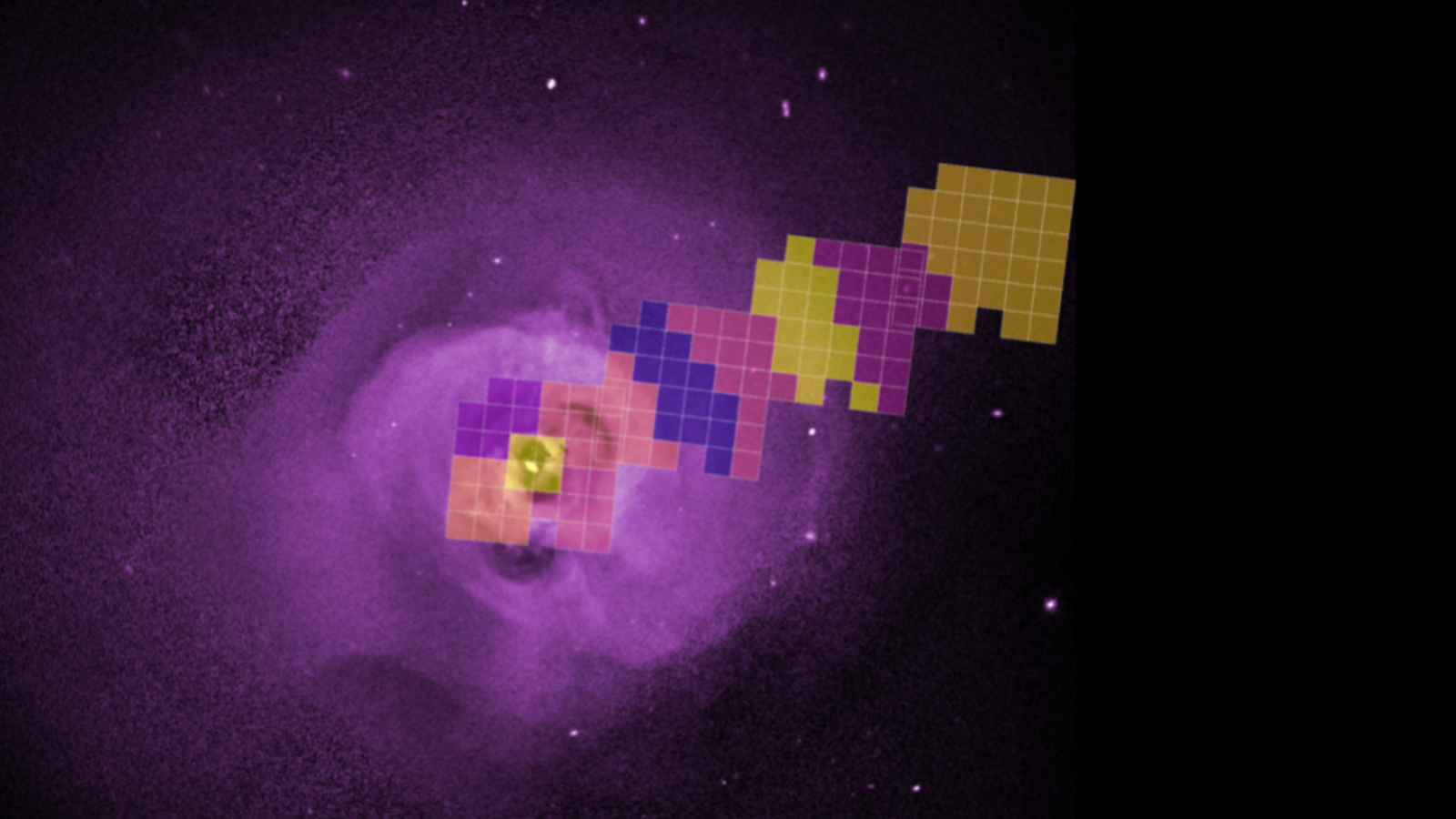

The team also investigated the motion of gas in the Perseus Cluster of galaxies, the brightest cluster in X-rays as seen from Earth. The brightness of this cluster allowed researchers to use XRISM data to map the motion of gas both around the center of the cluster and further out from its heart.

This revealed the "kick" delivered to the velocity of this gas by a supermassive black hole, as well as the motion of gas being driven by an ongoing merger between Perseus and a chain of galaxies.

This could answer the question of why stars aren't as densely packed into the cores of galaxy clusters as astronomers expect. The team theorizes that if the energy of the moving gas they tracked with XRISM was converted to heat, then this would prevent gas clouds from cooling enough to collapse and birth stars.

"It remains an open question whether this is the only heating process at work, but the results make it clear that turbulence is a necessary component of the energy exchange between supermassive black holes and their environments," McCall said.

XRISM continues to gather X-ray data that could provide an even clearer picture of the relationship between supermassive black holes and their home galaxies, as well as how this relationship changes as both age and evolve.

"Based on what we've already learned, I am positive we are getting closer to solving some of these puzzles," team member Irina Zhuravleva of the University of Chicago said.

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. whose articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space, Newsweek and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University. Follow him on Twitter @sciencef1rst.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.