Astronomers watch 2 supermassive black holes caught in a twisted dance with never-before-seen jet behavior

"This result shows that the Event Horizon Telescope is not only useful for producing spectacular images, but can also be used to understand the physics that govern black hole jets."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Astronomers have used the Event Horizon Telescope (EHT) to observe a violent cosmic dance between a suspected pair of supermassive black holes at the heart of a distant galaxy. The evidence for this tryst between cosmic monsters lies in the twisted properties of the jets that erupt around the black holes.

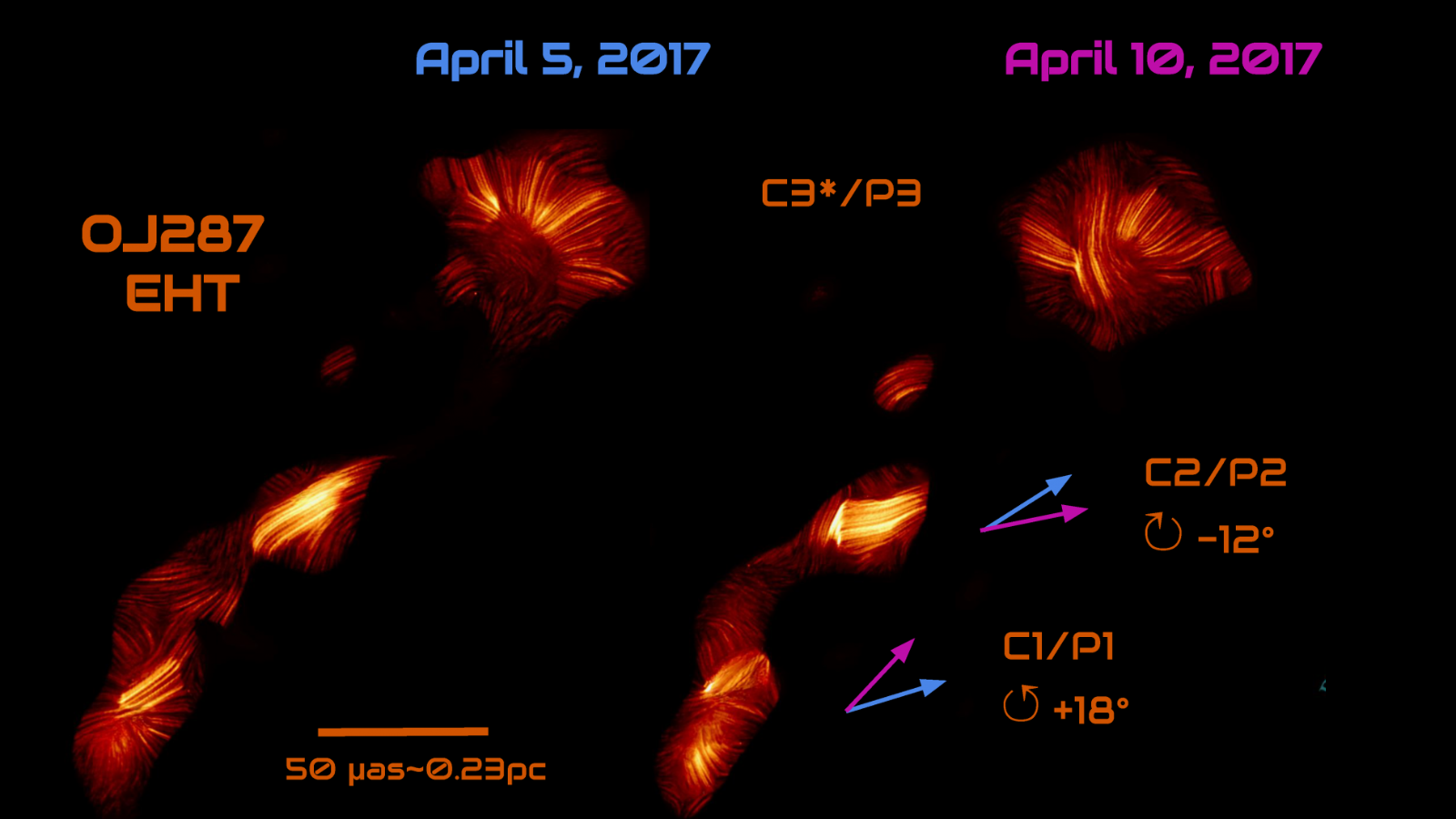

The supermassive black hole pair, or binary, lurks at the heart of the quasar OJ287, located at the center of a galaxy around 1.6 billion light-years away from Earth. Using a level of resolution that would be able to spot a tennis ball on the surface of the moon, the team spotted two shockwaves flowing down the jet of OJ287. The shocks, interestingly, were seen traveling at different speeds. And as they travel, passing through strong magnetic fields, these shockwaves appear to produce a phenomenon never seen before.

This is just the latest major black hole breakthrough delivered by the EHT, which in April 2017 captured the first-ever image of a black hole, the supermassive black hole M87*, released to the public in 2019. The network of telescopes followed this up with an image of Sagittarius A*, the Milky Way's own supermassive black hole, which the public got to see in 2022.

Article continues belowSince then, the EHT has continued to make waves in black hole science.

"This result shows that the EHT is not only useful for producing spectacular images, but can also be used to understand the physics that govern black hole jets," EHT team member Mariafelicia De Laurentis said in a statement. "Distinguishing observationally between what is due to geometry and what is instead the result of real physical processes is a key step in comparing theoretical models with observations."

Snapshots of a black hole jet

The team captured two snapshots of the OJ287 system on April 5, 2017, and then on April 10 in the same year. These revealed substantial changes in both the structure and polarization of the OJ287 that occurred over the course of just five Earth days. That is the shortest interval over which such changes have been observed in a black hole jet.

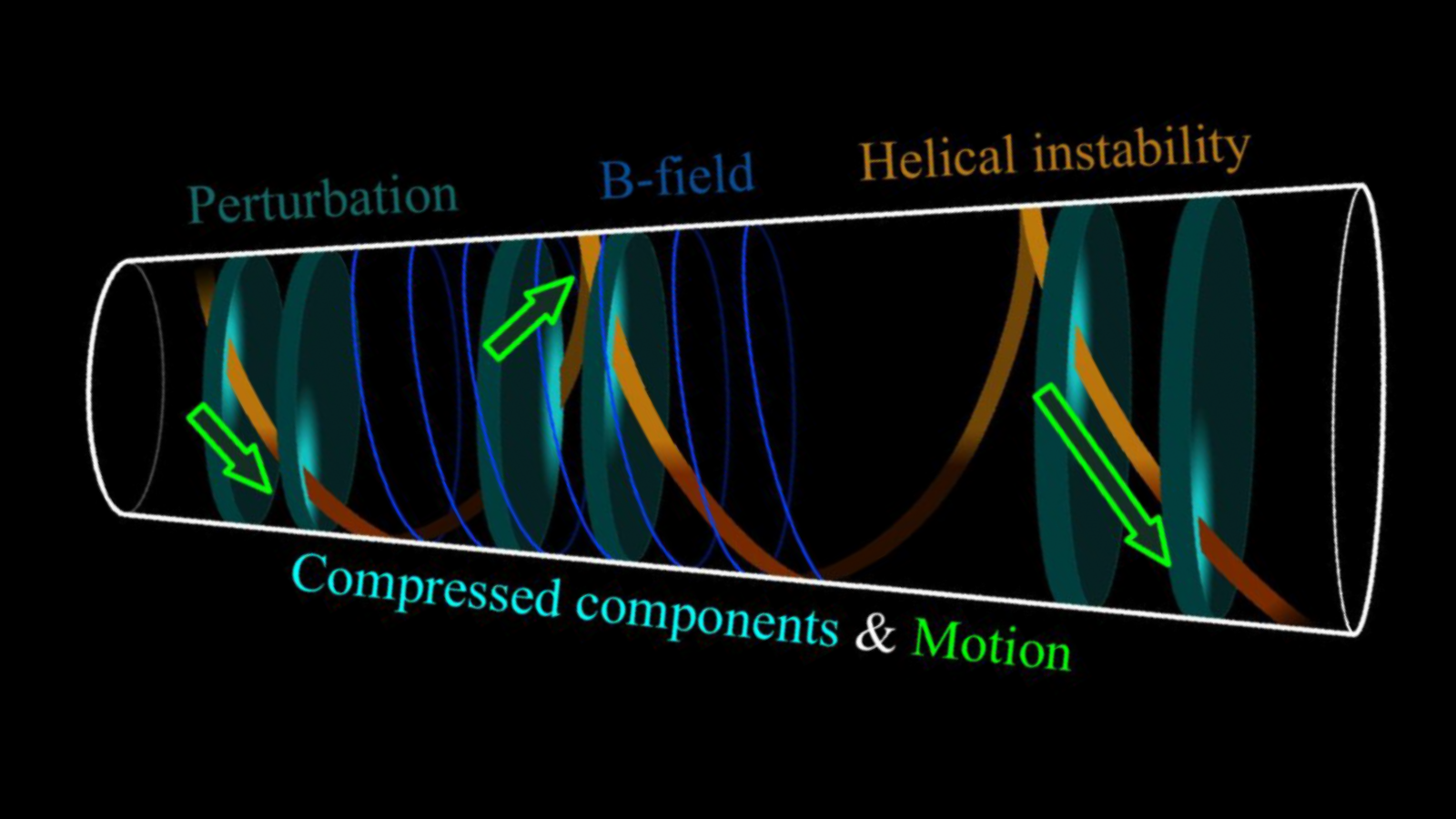

These changes are thought to be the result of shocks interacting with instabilities in velocity called Kelvin-Helmholtz instabilities. They result in a highly twisted structure within a jet, with three distinct polarized components: two slower and rotating in opposite directions to one another, one faster and rotating counterclockwise. This represented the first direct confirmation of a helical magnetic field with the jet of a black hole.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"We are spatially resolving the individual shock components and observing their interaction with Kelvin-Helmholtz instabilities," team member Ilje Cho of the Korea Institute for Astronomy and Space Science said. "This is the first time we have directly observed this interaction between shocks and instabilities in a black hole jet."

"These observed variations in the jet are usually interpreted in terms of a precession effect of the jet itself. However, precession models would expect the jet components to move ballistically along the jet," EHT team member Rocco Lico of the Italian National Institute for Astrophysics (INAF) said. "Our observations, however, indicate non-ballistic motions of these components, calling into question the precession hypothesis as the sole explanation for the observed morphology of the source." The rapid motions measured by the team suggested the kinetic energy of the particles exceeds the magnetic energy within the internal regions of the jet. This favors the development of Kelvin–Helmholtz instabilities, which arise due to the difference in velocity at the surface between the jet, which moves at speeds approaching light-speed, and the much slower surrounding matter. These instabilities can cause helix-shaped distortions that manifest as a "twisted" structure, just like that which the EHT spotted in the OJ287 jet.

The twisted structure of the jet observed in OJ287, the high degree of polarization of the three components, and the evolution of their polarization angles, indicate a complex interaction between Kelvin–Helmholtz instabilities and shocks in a jet permeated by a helical magnetic field.

"These rotations in opposite directions are the smoking gun," research team leader José L. Gómez of the Instituto de Astrofísica de Andalucía-Csic said in the statement. "When the shock wave components interact with the Kelvin-Helmholtz instability, they illuminate different phases of the helical structure of the magnetic field, producing the polarization oscillations we observe."

The team's model proposes that the Kelvin–Helmholtz instabilities generate filamentary structures that interact with propagating shocks in the jet.

"These interactions compress the magnetic field and amplify the emission in specific regions of the jet, explaining the observed features in both total intensity and polarized light, as well as the rapid variations in polarization angles and the apparent non-ballistic motions observed, despite the presence of a globally rectilinear jet," Lico said. "For the first time, high-resolution EHT data allow us to directly visualize these structures, providing concrete evidence of the interaction between jet instabilities, shocks, and helical magnetic fields."

OJ287 was the ideal candidate to make these observations because the dancing supermassive black holes in this pair are well known for their periodic outbursts, making it a unique laboratory to study black hole physics.

The team's research was published on Jan. 8 in the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics.

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. whose articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space, Newsweek and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University. Follow him on Twitter @sciencef1rst.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.