Nearby star's massive eruption could help astronomers unlock secret of superflares

It's a tough trick to catch a cosmic firework just as it explodes.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

It's a tough trick to catch a cosmic firework just as it explodes.

The universe is a really big place, full of transient events that flash into existence and then fade away quickly. We often see the aftermath, the lingering glow. But the very moment of ignition, that initial burst of energy? That's like trying to photograph a lightning strike without knowing where it will hit. Astronomers are really clever, and they've concocted new ways to do just that. They use a global network of telescopes, always watching the skies.

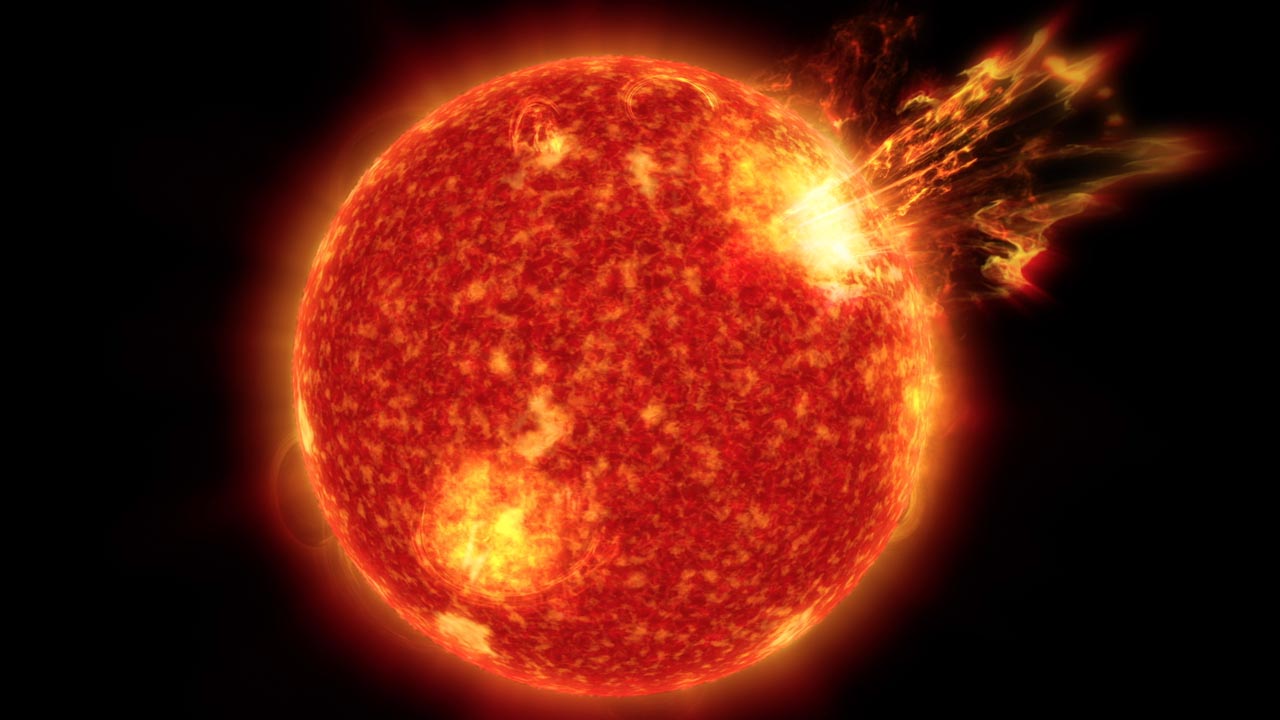

And sometimes, all that effort pays off. In November of 2024, a set of new eyes in space, the SVOM/GRM telescope, did something amazing. It caught an immense stellar detonation, a superflare from a star called HD 22468, right at its most energetic moment. This was the first hard X-ray triggered superflare ever observed from an RS CVn-type star. This monster burst released about as much energy as our sun puts out in a few months, all in a matter of moments. It's like watching a star sneeze out a sun's worth of energy. This observation gives us a smoking gun, a direct look into the brutal physics of these stellar events.

Article continues belowA superflare is a giant, sudden explosion on the surface of a star, like a cosmic firework. It happens when twisted magnetic fields snap, releasing a huge amount of energy and making the star temporarily much brighter, especially in high-energy light. Our own sun has flares, but these superflares are thousands or even millions of times more powerful. These are events that could sterilize planets if they happened too close, washing them in deadly radiation. We really need to understand them.RS CVn-type stars are often close pairs of stars, gravitationally bound, orbiting each other. This proximity can really stir up their magnetic fields, making them prone to massive outbursts. These stars have really active coronas, the super-hot, wispy "hair" around them. This corona gets all twisted up with magnetic fields, building up tension until, boom, a flare lets it all out. Catching these events as they begin, especially in the highest energy hard X-rays, is incredibly difficult.

Usually, astronomers come up empty, seeing just the lingering effects of such explosions. Getting a hard X-ray trigger, as reported in a paper posted to the online preprint repository ArXiv in January and accepted for publication in The Astrophysical Journal, means we're seeing the very start of the show, a way to test the theories of how these exotic flares get started.Analyzing this flood of data, scientists pieced together the flare's brutal physics. The multi-wavelength light curves, like stock market graphs for a star's brightness, showed a clear sequence. The hard X-ray peak came first, intense and quickly, followed by a longer, scorching soft X-ray and optical glow. This timing is a crucial detail, telling us about the energy release mechanism. They found superheated stellar material, reaching temperatures from 10 million up to 100 million degrees Kelvin. This extreme heat was driven by thermal processes and high-energy particle acceleration.

Magnetic reconnection, the snapping and rejoining of those twisted magnetic field lines, is believed to be the fundamental mechanism driving stellar flares. It's a complex dance of energy, but these observations help us see the steps. Observations like this recent superflare gives us a clearer picture of how magnetic fields store and release vast amounts of energy in stellar coronas. This kind of detailed timing and temperature data allows scientists to tweak their computer simulations, making them more accurate. Better models mean we can better predict stellar behavior, understand how stars lose mass, and even get a handle on the habitability of planets around other active stars. It's a critical step in building a complete picture of what is and isn't allowed in this universe when it comes to stellar fireworks.

We just keep staring at a whole bunch of stars for a really long time, and sometimes, we get lucky.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Paul M. Sutter is a cosmologist at Johns Hopkins University, host of Ask a Spaceman, and author of How to Die in Space.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.