Goodbye Goldilocks: Scientists may have to look beyond habitable zones to find alien life

Scientists may need to broaden their horizons in their search for alien life.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

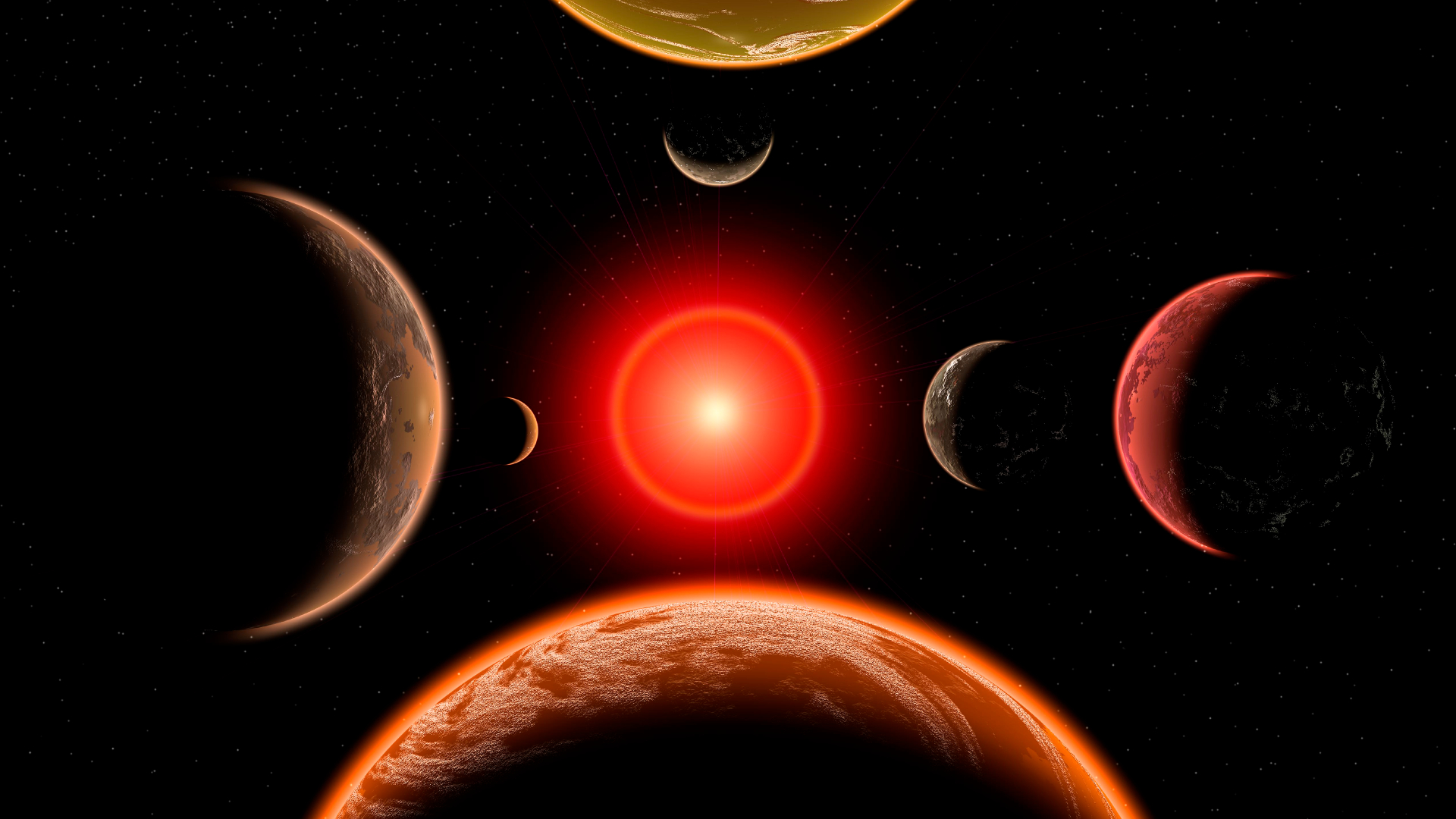

Scientists argue that limiting the search for life strictly to a star’s traditional habitable zone is too restrictive. That is in light of new climate models, and observations that suggest that liquid water—and therefore potentially life-supporting conditions—can exist well beyond these classical boundaries.

The habitable zone is defined as the region around a star where a planet could maintain liquid water on its surface without turning to ice or gas.

The fact that this water is neither too hot nor too cool has also led to the habitable zone being nicknamed the Goldilocks zone. In our solar system, this zone begins at around the orbit of Venus, the second planet from the sun, past the orbit of Earth, and out to roughly the orbit of Mars.

“[However,] this concept is rooted in the principle that liquid water is necessary for biochemical processes essential to life,” writes a team of researchers in a paper published on Jan. 12 in the Astrophysical Journal. “Although other factors, such as chemical energy sources, elemental diversity, and long-term environmental stability, are also important.”

Using an analytical climate model, the scientists have shown that tidally locked planets—which always show the same face to their star—can maintain liquid water on their permanent night side, even when orbiting much closer to their star than the traditional inner edge of the habitable zone.

“Initially, this configuration raised concerns about extreme temperature gradients and atmospheric collapse on the dark side,” the team writes. “However, 3D climate models have demonstrated that given a sufficient atmospheric pressure, or the presence of an ocean, efficient heat redistribution between the day and night sides can stabilize temperatures and maintain habitable conditions.”

This suggests that for tidally locked planets, common around small M-class and K-class stars, the inner edge of the habitable zone may actually lie closer to the star than in the case of rapidly rotating planets. This extended habitable zone could help explain recent observations made by the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) of water vapor and other volatile gases in the atmospheres of warm super-Earths closely orbiting their M dwarf stars.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

“Signs of water vapor and volatiles have been detected in JWST transmission spectra of small exoplanets,” they write. “Some of these exoplanets are closer to their M dwarf hosts than the inner [habitable zone] boundary […] Water detection on such planets is intriguing, since one would doubt the survival of atmosphere and water under such harsh conditions.”

These findings suggest that such planets can retain significant amounts of water despite lying outside the classical habitable zones—and this doesn’t apply to planets orbiting their stars too closely. The team argues that the habitable zone should be extended in both directions. Even on cold planets far from their stars, liquid water can exist beneath thick ice layers, as subglacial lakes or through internal heating. Similar environments on Earth, such as Antarctica’s subglacial lakes, support microbial life, demonstrating that surface liquid water is not the only possible habitat.

Through a reassessment of habitable zone models and boundary calculations, this study expands the range of worlds considered potentially habitable, revealing new targets in the search for life.

A chemist turned science writer, Victoria Corless completed her Ph.D. in organic synthesis at the University of Toronto and, ever the cliché, realized lab work was not something she wanted to do for the rest of her days. After dabbling in science writing and a brief stint as a medical writer, Victoria joined Wiley’s Advanced Science News where she works as an editor and writer. On the side, she freelances for various outlets, including Research2Reality and Chemistry World.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.