Proteins before planets: How space ice may have created the 1st building blocks of life

"We used to think that only very simple molecules could be created in these clouds. But we have shown that this is clearly not the case."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

The chemistry that built life on Earth may have begun in deep space, according to a new study. The discovery could help to unravel one of science's central questions: what are the origins of life's molecular building blocks?

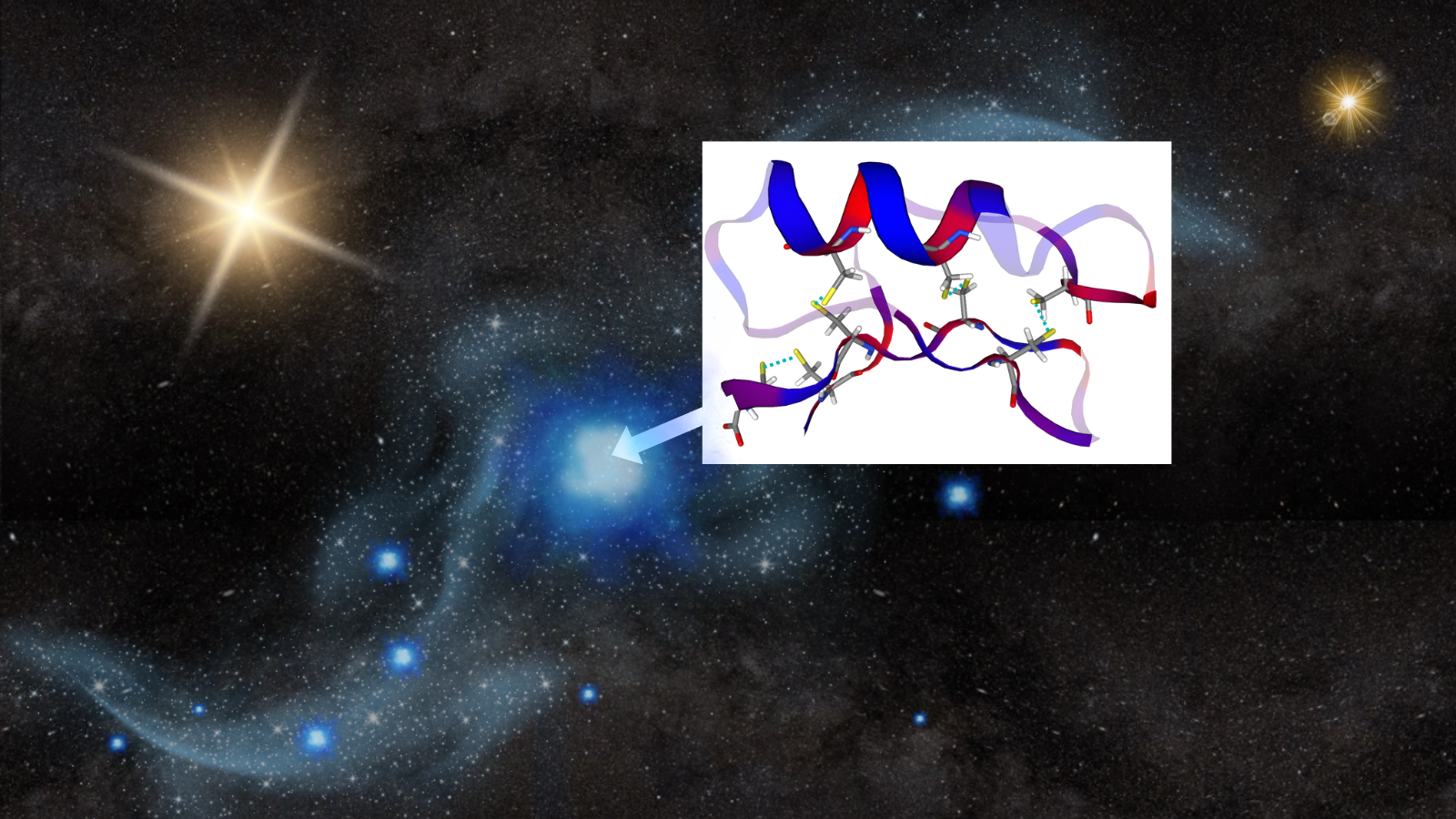

Astronomers have detected simple organic molecules drifting through interstellar clouds and preserved in meteorites and comets, indicating that biologically important compounds can form in space and be delivered to planetary surfaces. However, one crucial step has remained unresolved: how amino acids could link together under the harsh conditions of space to form short molecular chains called peptides.

It is these chains of molecules that serve as the first building blocks of proteins, essential for living things.

"We already know from earlier experiments that simple amino acids, like glycine, form in interstellar space. But we were interested in discovering if more complex molecules, like peptides, form naturally on the surface of dust grains before those take part in the formation of stars and planets," research team member and Aarhus University researcher Sergio Ioppolo said in a statement.

Ioppolo and his colleagues demonstrated that peptides can actually form inside icy dust grains exposed to radiation under space-like conditions. In laboratory experiments, they produced glycylglycine—the simplest possible dipeptide—by cooling glycine to cryogenic temperatures, of minus 436 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 260 degrees Celcius), replicating the icy mantles that coat cosmic dust grains, and then bombarding the frozen sample with high-energy protons, a stand-in for cosmic rays.

The results reveal a previously unknown pathway for building protein precursors that does not require liquid water—long thought to be essential—that can operate in the extreme conditions of interstellar space. "All types of amino acids bond into peptides through the same reaction. It is therefore very likely that other peptides naturally form in interstellar space as well," said co-author Alfred Thomas Hopkinson, of Aarhus University. "We haven't looked into this yet, but we are likely to do so in the future."

Alongside glycylglycine, the team observed the formation of both ordinary water and a form of water in which hydrogen atoms are replaced by deuterium, an isotope of hydrogen with an extra neutron, along with a variety of other complex organic molecules.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"We used to think that only very simple molecules could be created in these clouds. The understanding was that more complex molecules formed much later, once the gases had begun coalescing into a disk that eventually becomes a star," Ioppolo explained. "But we have shown that this is clearly not the case."

The results suggest that ionizing radiation supplies enough energy to break and reform chemical bonds, allowing amino acids trapped in ice to link together without liquid water. In effect, cosmic radiation becomes a chemical engine, driving complexity in environments previously thought too cold and inert to support such reactions.

This discovery significantly broadens the range of environments in which life’s precursors might form. Rather than being restricted to warm, wet settings like early Earth’s oceans or hydrothermal vents, peptide synthesis could occur in the cold interstellar medium itself.

"Eventually, these gas clouds collapse into stars and planets. Bit by bit, these tiny building blocks land on rocky planets within a newly formed solar system. If those planets happen to be in the habitable zone, then there is a real probability that life might emerge," Ioppolo explained. "That said, we still don't know exactly how life began. But research like ours shows that many of the complex molecules necessary for life are created naturally in space.

"There's still a lot to be discovered, but our research team is working on answering as many of these basic questions as possible. We've already discovered that many of the building blocks of life are formed out there, and we'll likely find more in the future."

The team's research was published on Jan. 20 in the journal Nature Astronomy.

A chemist turned science writer, Victoria Corless completed her Ph.D. in organic synthesis at the University of Toronto and, ever the cliché, realized lab work was not something she wanted to do for the rest of her days. After dabbling in science writing and a brief stint as a medical writer, Victoria joined Wiley’s Advanced Science News where she works as an editor and writer. On the side, she freelances for various outlets, including Research2Reality and Chemistry World.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.