Saturn's moon Enceladus is shooting out organic molecules that could help create life

Could Saturn's frozen moon be the best place to look for life in the solar system?

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

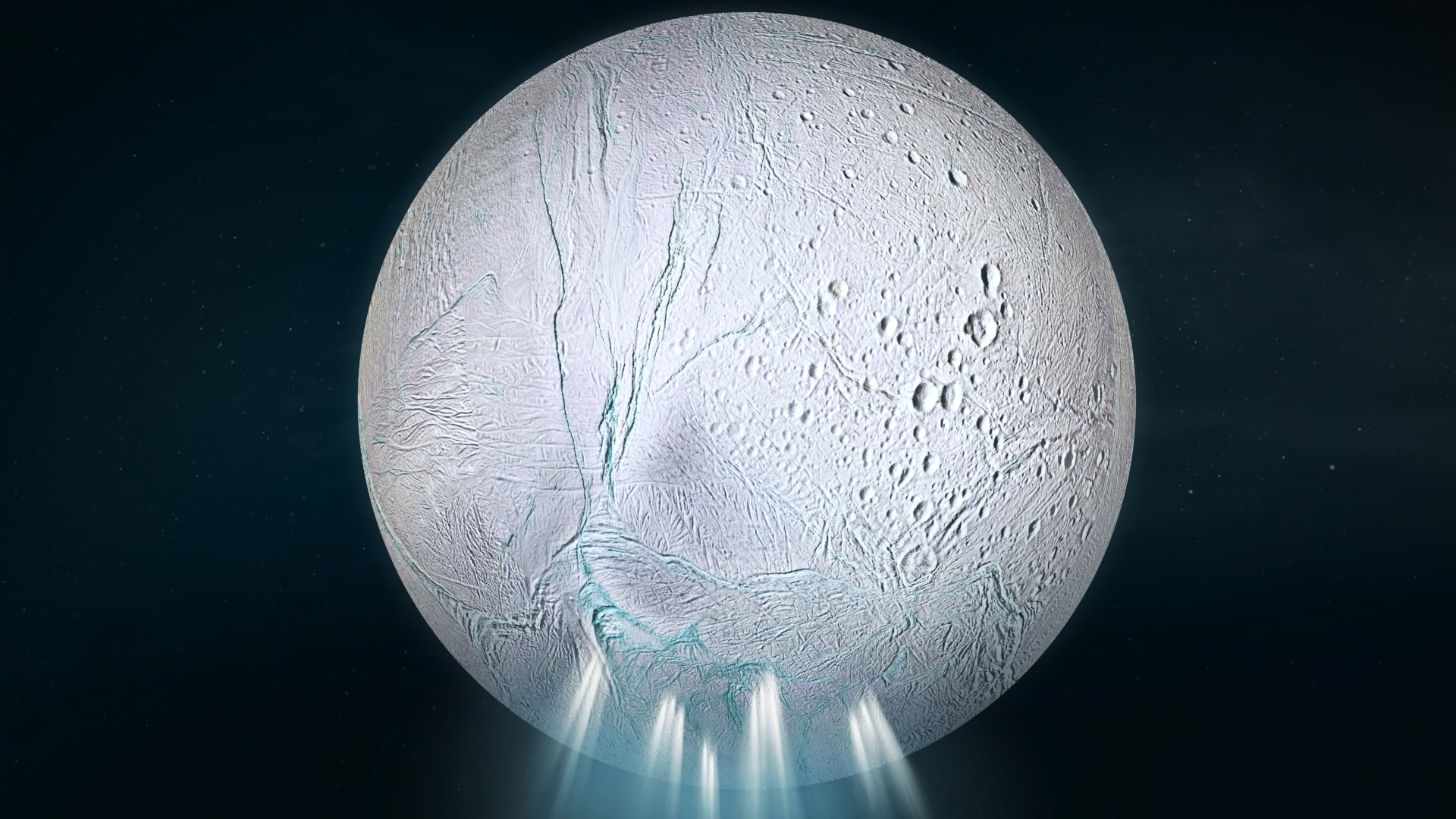

Complex organic molecules that form part of the chain of chemical reactions that can result in life's building blocks have been found in the watery geysers of Enceladus, almost twenty years after the plumes were first sampled by NASA's Cassini spacecraft.

Cassini's mission to the ringed planet Saturn ended in 2017, but scientists are still making findings buried deep in its treasure trove of archived data.

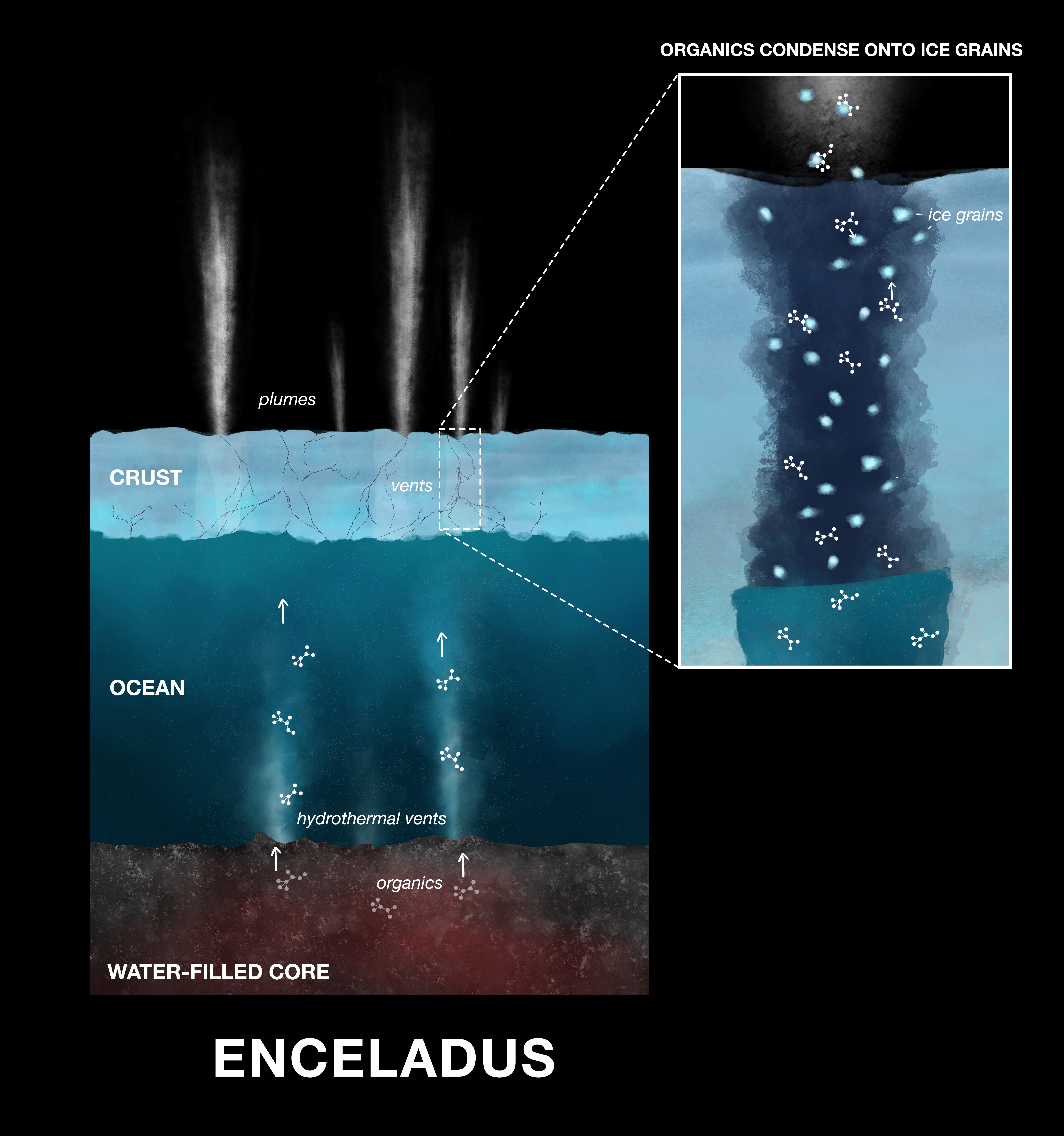

The discovery of these organic molecules ("organic" meaning they contain carbon) strengthens the case for the icy moon Enceladus being of astrobiological interest. In 2005, Cassini discovered that plumes of water vapor were spraying into space from huge fissures in Enceladus' surface. These fissures are believed to lead to a subsurface ocean within the 310-mile-wide (500-kilometer-wide) moon of Saturn, and it is this ocean that provides the water for the plumes. While some of the material from the plumes snows back onto the surface of Enceladus, most of it escapes into space where it forms a diffuse ring, called the E-ring, encircling Saturn at a greater distance from the planet than most of the rest of its system of rings.

"Cassini was detecting samples from Enceladus all the time as it flew through Saturn's E-ring," Nozair Khawaja of the Freie Universität Berlin and the University of Stuttgart in Germany said in a statement. "We had already found many organic molecules in these ice grains, including precursors for amino acids."

However, there has always been caution over the findings from the E-ring, because charged particles trapped in Saturn's magnetosphere bombard the icy particles in the E-ring, instigating chemical reactions. It had been unclear whether the organic molecules present in the ring had come from Enceladus' ocean or whether they had been formed by the reactions triggered by the radiation.

However, Cassini also flew directly through some of the plumes, so Khawaja went back to archive data from 2008 and the results from the spacecraft's Cosmic Dust Analyzer (CDA), which was an instrument led by scientists at the University of Stuttgart. With painstaking precision, Khawaja's team took apart the CDA data, and their new analysis found evidence for organic molecules that had been missed the first time around.

When Cassini flew through the plumes, icy grains struck the CDA's detector at 11 miles (18 kilometers) per second, which is faster than the 7.5 miles (12 kilometers) per second in the E-ring. These grains, only just spewed out of the ocean, contain pristine material that had not yet been altered by radiation.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"The ice grains contain not just frozen water, but also other molecules including organics," said Khawaja. "At lower impact speeds, the ice shatters and the signal from clusters of water molecules can hide the signal from certain organic molecules. But when the ice grains hit the CDA fast, water molecules don’t cluster and we have a chance to see these previously hidden signals."

The results showed that the same organic molecules present in the E-ring are also in the plumes, which tells scientists that they must originate from the ocean and are not a product of space radiation. Khawaja's team also found a variety of other organic molecules that had not been detected before in relation to Enceladus' plumes. These include aliphatic, (hetero)cyclic ester/alkalines, ethers/ethyl and possibly nitrogen- and oxygen-bearing compounds. On Earth, these molecules are part of a chain of chemical reactions that lead to life's building blocks.

"There are many possible pathways from the organic molecules we found in the Cassini data to potentially relevant compounds, which enhances the likelihood that the moon is habitable," said Khawaja.

There is a note of caution, however.

Recent research led by Grace Richards of the Istituto Nazionale di Astrofisica e Planetologia Spaziale (INAF) in Rome has found the bombardment of radiation that scientists had been so concerned had altered the material in the E-ring can also create organic molecules on the surface of Enceladus. This includes on the ground in and around the fissures, called "tiger stripes," from which the geysers emanate. If Richards is correct, this would seriously confuse the issue and there would be no way to know whether the organic molecules detected by Cassini in the plumes are from the ocean or produced by radiation in the tiger stripes and are dragged into space by the plumes.

One way to solve the issue would be to land on Enceladus and sample fresh ice directly. Indeed, this is the plan, with the European Space Agency considering a mission that would feature an orbiter/lander combo arriving at Enceladus in 2054. Only by getting ground truth can scientists know for sure whether Enceladus' ocean really does feature the kind of complex chemistry that can potentially lead to life.

The new results from Cassini's Cosmic Dust Analyzer were published on Oct. 1 in the journal Nature Astronomy.

Keith Cooper is a freelance science journalist and editor in the United Kingdom, and has a degree in physics and astrophysics from the University of Manchester. He's the author of "The Contact Paradox: Challenging Our Assumptions in the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence" (Bloomsbury Sigma, 2020) and has written articles on astronomy, space, physics and astrobiology for a multitude of magazines and websites.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.