Astronomers discover chemicals that could seed life in the core of a developing star

An organic molecule called methanimine was found scattered throughout a dense clump of gas and dust 554 light-years away.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Astronomers recently searched the gas cloud of a yet-unborn star for a chemical that may seed future planets with the basic ingredients for life.

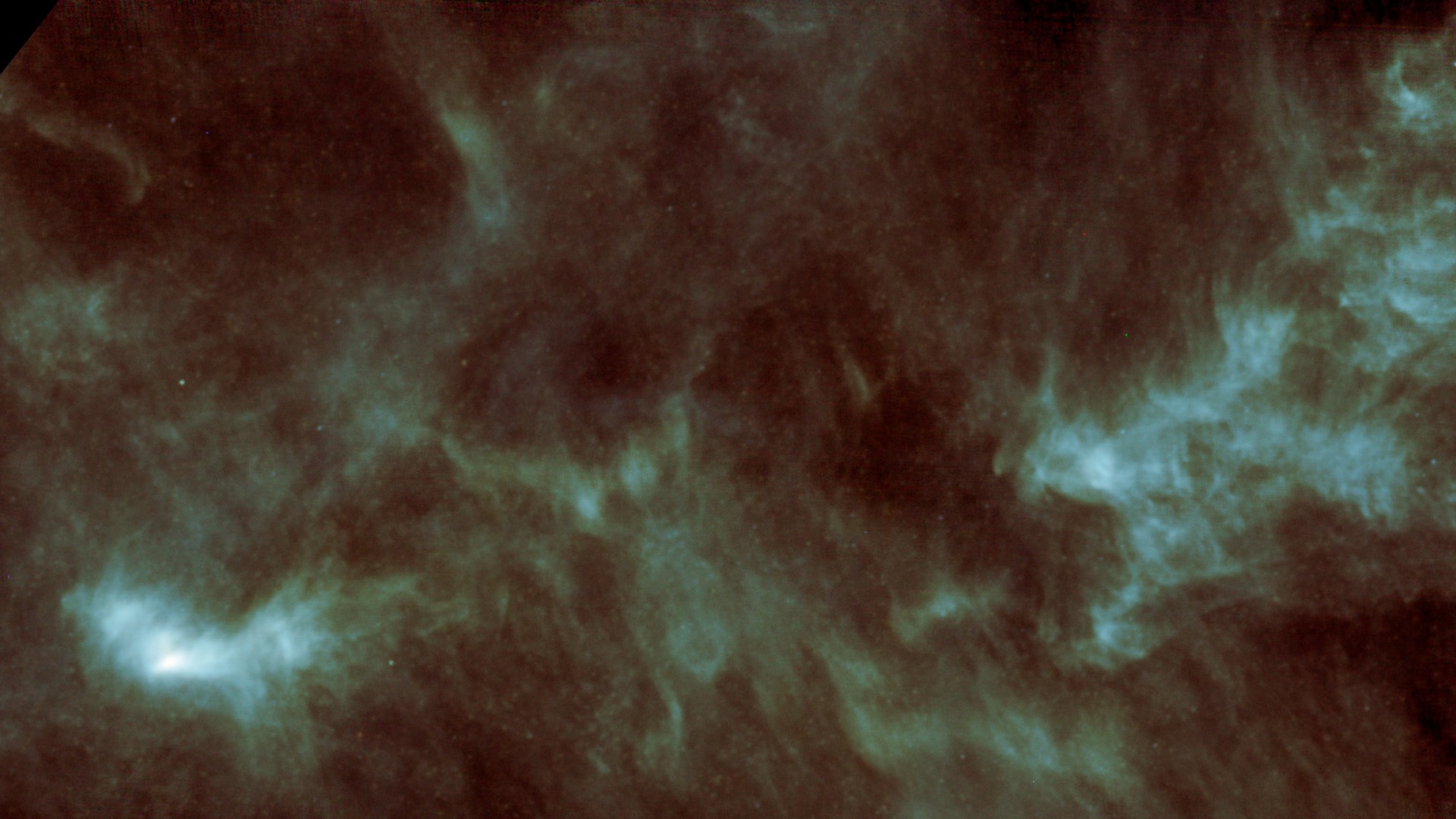

Astronomer Yuxin Lin and colleagues found an organic molecule called methanimine scattered throughout a dense clump of gas and dust 554 light-years away. The cloud, called L1544 and found within the Taurus Molecular Cloud, will eventually become a star with a system of planets, and if Lin and colleagues are right, those exoplanets may form with a "starter kit" of organic molecules like methanimine — courtesy of chemical reactions that are going on right now in the cold, dormant molecular cloud.

Astronomers have spotted methanimine in a surprising range of places in the universe, from very hot and turbulent places like the cores of newborn stars to frigid grains of ice drifting through interstellar space. One of the most interesting places methanimine has turned up is what astronomers call a pre-stellar core: a dense knot of gas and dust, poised on the brink of collapsing under its own gravity to form a newborn star. Think of a pre-stellar core — like L1544, located 554 light years away — as all the ingredients for a star system, with some assembly required.

Article continues belowOrganic chemistry starter kit

Methanimine (CH2NH2), not to be confused with anything featured on "Breaking Bad," is a fairly simple molecule, as organic chemistry goes. It sits about halfway along the chain of chemical reactions that lie between a handful of stray atoms and an amino acid (one of the much larger organic molecules that combine to form proteins). And even if you break a methanimine molecule apart, you still have a handful of key ingredients in the chemistry of life: carbon, hydrogen, and nitrogen.

Understanding how molecules like methanimine form in pre-stellar cores like L1544 could shed new light on how planetary systems get their "starter kits" of ingredients for organic chemistry, from the raw elements all the way up to complicated molecules like amino acids.

Potentially habitable worlds, some assembly required

For what's essentially the embryonic form of a massive star, L1544 is a remarkably tranquil place. It's part of the Taurus Molecular Cloud, where other dense clumps of material like L1544 are collapsing under their own gravity to form new stars, each hundreds of thousands of times the mass of the sun.

But for now, L1544 is a quiescent backwater. Material is gradually falling inward from the clump's warmer edges onto the cold, dense center, but it's a very slow rain, something like the calm before the thermonuclear storm of star formation.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The other layers of the cloud, where material is less densely clumped but temperatures are warmer, is where most of the methanimine seems to be forming. As material from those outer layers falls inward toward the center, methanimine gets distributed across most of the pre-stellar core. That makes it likely that methanimine will keep forming right up until the moment of collapse — and that some of it will probably remain in the outer part of what will, one day, be a planetary disk orbiting a brand-new star.

As planets gradually coalesce out of the disk, many of them may come with the basic ingredients for amino acids baked in — and if any of them are habitable, those molecules may eventually give rise to life.

"This demonstrates that key prebiotic nitrogen and carbon chemistry remains active even in the cold, quiescent phase preceding collapse, ensuring that organic precursors such as CH2N2 can be inherited by the next generation of forming stars and planets," wrote Lin and colleagues in their recent paper.

Lin and colleagues published their findings in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

Kiona Smith is a science writer based in the Midwest, where they write about space and archaeology. They've written for Inverse, Ars Technica, Forbes and authored the book, Peeing and Pooping in Space: A 100% Factual Illustrated History. They attended Texas A&M University and have a degree in anthropology.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.