Did the Viking missions discover life on Mars 50 years ago? These scientists think so

The key to solving the mystery of the Viking results is the discovery of perchlorate on the Martian surface in 2008.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

NASA's Viking missions to Mars may have discovered evidence for life on the Red Planet after all, according to scientists who are seeking to correct what they believe to be a 50-year-old mistake that has led everybody to think that Mars is lifeless.

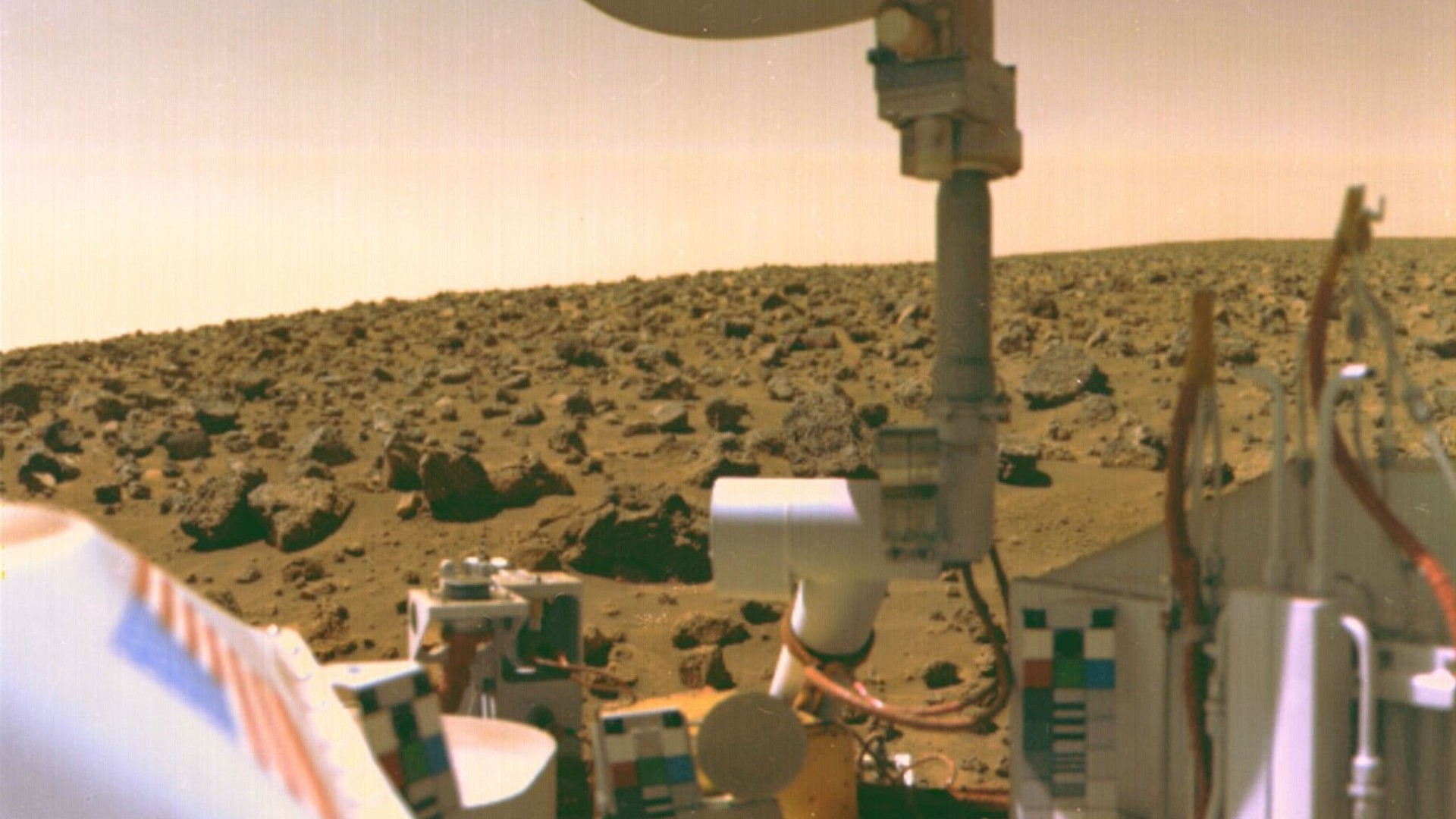

Viking 1 and Viking 2 landed on Mars in 1976. On board they carried three life-detection experiments, which produced positive results. But the apparent failure of another instrument, the Gas Chromatograph-Mass Spectrometer (GC-MS), to detect organic molecules necessary for life led Viking Project Scientist Gerald Soffen to conclude, "No bodies, no life."

However, scientists led by Steve Benner, a professor of chemistry at the Foundation for Applied Molecular Evolution in Florida, now argue that the Viking data shows something quite different to what the textbooks say.

Article continues below"The GC-MS showed an absence of organic molecules, or at least that was the [Viking team's] interpretation," Benner told Space.com. "The problem is that we now know that it did find organic molecules!"

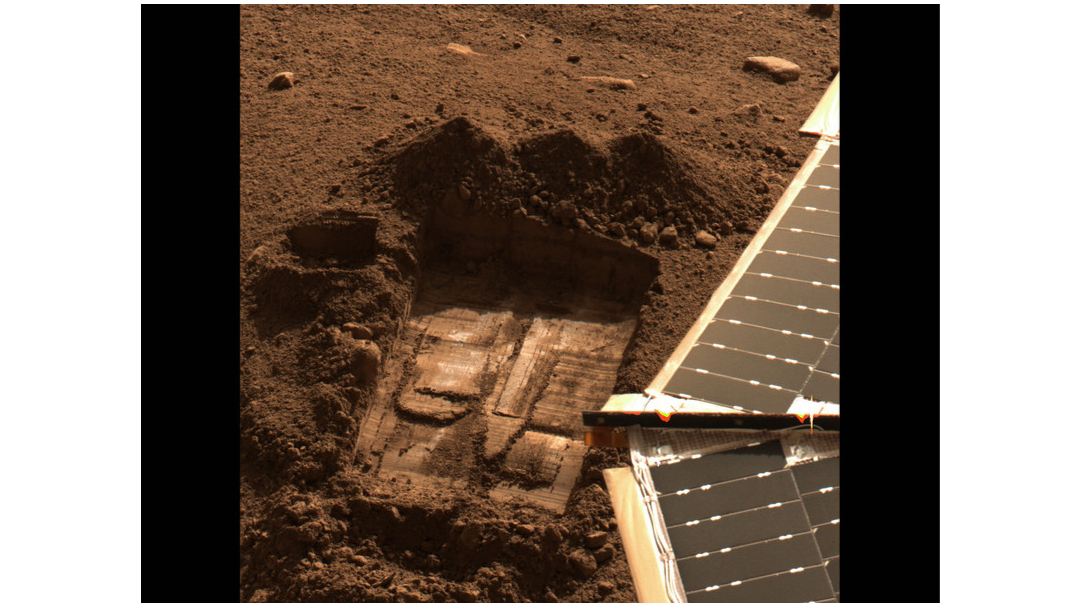

The GC-MS worked by heating samples of Martian dirt — first to 120 degrees Celsius (248 degrees Fahrenheit) to remove any excess carbon dioxide from Mars' atmosphere, and then to 630 degrees C (1,166 degrees F) in order to vaporize any organics present in the dirt so that they could be analyzed by the mass spectrometer.

Puzzlingly, all that the mass spectrometer detected was an unexpected second burst of carbon dioxide and a small quantity of methyl chloride and methylene chloride, when instead there should have been some organic molecules present, if only from meteoritic debris that had built up over billions of years. For there to be none at all, argued the Viking team, required an unknown oxidant. Meanwhile, the carbon dioxide was assumed to have been left over from being observed by the container holding the sample, while methyl chloride was thought to be terrestrial contamination from cleaning solvents originating from the clean room on Earth where the instrument was assembled. This conclusion was bolstered by the fact that, during in-flight tests on the way to Mars, freons such as chlorofluorocarbons that had come from the clean room had been detected.

The problem with that interpretation, according to Benner, is that "methyl chloride is not a cleaning solvent — it's a gas that boils at minus 24 degrees Celsius [minus 191 F]."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Nevertheless, the Viking team claimed that, not only had an oxidant destroyed the organics, but that it could also explain away the other three supposedly positive life detection tests, which measured the apparent metabolization of radioactive carbon, the emission of oxygen and "carbon fixing" (the process by which life turns inorganic carbon into organic compounds). The complication is that, to explain the apparent metabolization of radioactive carbon in the so-called Label Release experiment, the oxidant would have to be very strong. The Viking team concluded that this mystery oxidant was some kind of peroxide, even though peroxides have never been detected on the Red Planet.

This explanation never sat well with some scientists, particularly Gil Levin, who was the lead investigator on the Label Release experiment and who never accepted that his experiment hadn't found life.

But if there is microbial life on Mars, where are the organic molecules? While organic molecules have been found on Mars since by the Curiosity and Perseverance rovers, most of them are believed to originate from abiotic sources, like meteorites, and although Viking had less sensitive mass spectrometers than the modern rovers, it still doesn't explain why Viking saw no organics at all. Benner said that the answer to these puzzling results came in 2008, when NASA's Phoenix lander discovered perchlorate on the Martian surface. Perchlorate is also an oxidant, strong enough to destroy organics from meteorites over the course of millennia, but not strong enough to be the oxidant that the Viking team were looking for to explain the Label Release results.

This misses the point, according to Benner and his colleagues.

"In 2010, Rafael Navarro-González [a NASA astrobiologist who worked on the Curiosity rover mission] showed that organics plus perchlorate produces methyl chloride and carbon dioxide," said Benner.

In fact, the reaction produces 99% carbon dioxide and 1% methyl chloride, which would explain the extra burst of carbon dioxide and the "cleaning solvent" seen when the sample was heated to 630 degrees C.

"So now we know that the GC-MS didn't fail to discover organics — it did discover them, through their degradation products," said Benner.

The detection of organic molecules by GC-MS then strengthens the argument that the three life-detection experiments on the two Viking landers — the Label Release, the Pyrolytic Release and the Gas Exchange experiment — perhaps found life after all, which would remove the need for a strong and undiscovered oxidant.

To this end, Benner and his colleagues have even developed a model for what these purported Martian microbes might be like. They call it the BARSOOM model: Bacterial Autotrophs that Respire with Stored Oxygen On Mars (Barsoom is what the natives of Mars referred to their planet as in the novels of Edgar Rice Burroughs).

Autotrophic bacteria use photosynthesis to produce their own food, only to go dormant at night, storing oxygen that they have created to use when they reawaken. This would explain the emission of oxygen detected by Viking's Gas Exchange experiment.

Benner thinks that the initial misinterpretation of the GC-MS results has set astrobiological research on Mars back 50 years. Instead of a healthy debate about the merits of the Viking evidence for life on Mars, discussion was shut down and the official line ever since, repeated in textbooks, is that the Viking missions found no evidence for life.

To make up for lost time, Benner is now calling for that back-and-forth debate — the very nature of the scientific method — to begin in earnest now, the 50th anniversary year of the Viking 1 and 2 Mars landings.

The conclusions of Benner's team, which also includes Dirk Schulze-Makuch of Technische Universität Berlin and Jan Spacek and Clay Abraham, also of the Foundation for Applied Molecular Evolution, was published last month in the journal Astrobiology.

Keith Cooper is a freelance science journalist and editor in the United Kingdom, and has a degree in physics and astrophysics from the University of Manchester. He's the author of "The Contact Paradox: Challenging Our Assumptions in the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence" (Bloomsbury Sigma, 2020) and has written articles on astronomy, space, physics and astrobiology for a multitude of magazines and websites.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

![Viking Lander animation (1970s) [HD source] - YouTube](https://img.youtube.com/vi/1dCWCJ7XbuM/maxresdefault.jpg)