Life on Mars? 40 Years Later, Viking Lander Scientist Still Says 'Yes'

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

In 1976, NASA's twin Viking landers touched down on Mars in an attempt to answer a weighty question: Is there life on the Red Planet?

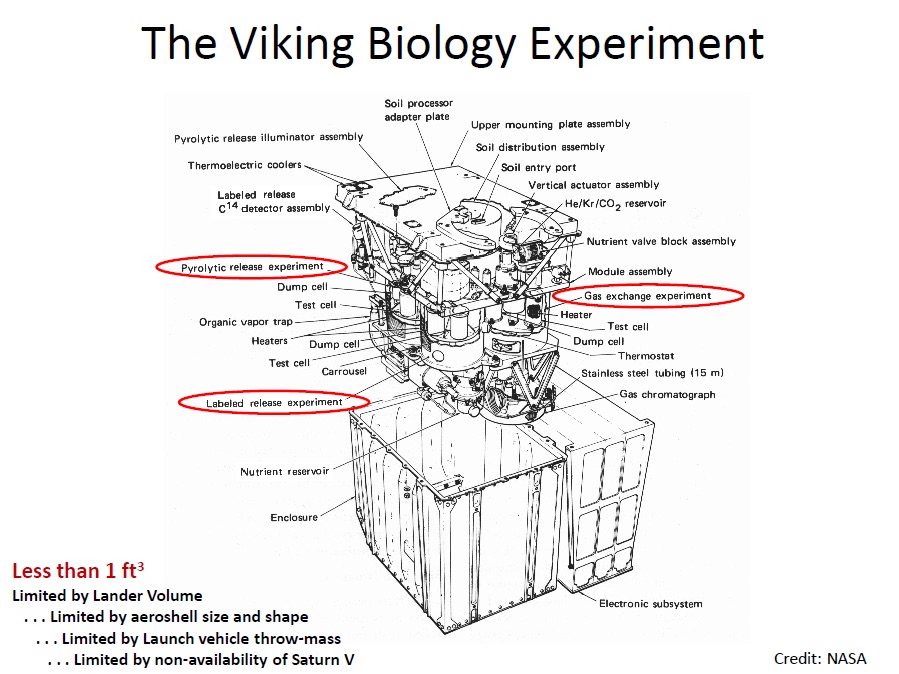

Gilbert Levin was the principal investigator of the Vikings' Labeled Release (LR) life-detection experiment. The instrument got positive responses at both landing locales. However, scientists did not reach a consensus on whether his results were proof of life.

In 1997, Levin concluded that the experiment had, indeed, detected life on Mars — and he has championed that viewpoint ever since. [The Search for Life on Mars: A Photo Timeline]

Article continues belowCall for follow-up

Now, more than four decades after the Viking landings — and with a lot more information about Mars in hand — Levin believes that NASA hasn't properly followed up on the Viking landers' results.

"I am certain that NASA knows there is life on Mars," he said this past July on David Livingston's popular online program "The Space Show."

Levin called for a re-examination of Viking LR data by an objective panel. But there's more.

Over the past 40 years, a succession of orbiters, landers and rovers has gathered evidence that life exists on Mars today, Levin said.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

There is "substantial and circumstantial evidence for extant microbial life on Mars," he said on "The Space Show."

Methane spikes

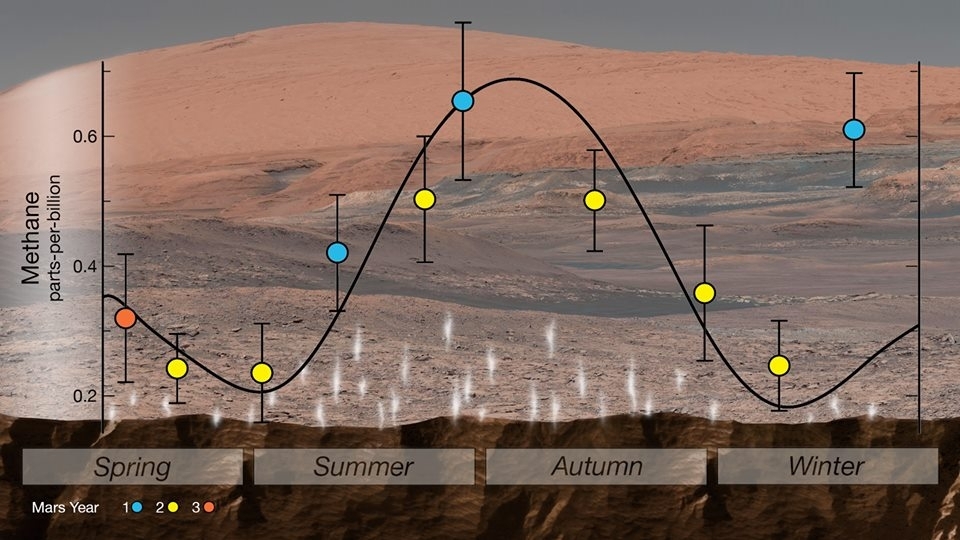

As an example, Levin noted that NASA's Curiosity rover has found cyclical and seasonal spikes in Mars methane. More than 90 percent of the methane in Earth's atmosphere is generated by microbes and other organisms.

"This is really hard to ignore as evidence for life," Levin said.

However, water-rock chemistry can also produce methane, so it's not persuasive evidence of life, Curiosity mission team members and other scientists have said.

Curiosity has also discovered organic molecules in 3-billion-year-old sedimentary rocks near the surface. Organics are the carbon-containing building blocks of life as we know it. But again, they're not convincing evidence of life by themselves; naturally occurring organics have also been spotted on asteroids, for example.

Water, water and more water

Then there's the July 2018 news from the European Space Agency's Mars Express mission: The orbiter apparently spotted an underground lake beneath a mile of ice near the Red Planet's south pole.

Various spacecraft have found evidence of water on Mars over the years, Levin said, and now "we are deluged with an underground lake … so water is no longer the problem."

Levin also pointed to Curiosity imagery that can be interpreted as depicting fossilized stromatolites, structures that are built by colonial microbes here on Earth. There are intriguing similarities between ancient sedimentary rocks on Mars and structures shaped by microbes on Earth, he said.

Everything that we have learned about environmental conditions on Mars, Levin said, would permit terrestrial microorganisms to survive — and that includes the harsh radiation, the low pressure and the frigid temperatures.

As for present-day life on the Red Planet, "it's getting to the point where the shoe is on the other foot," Levin said. "It's very hard to image a sterile Mars." [Ancient Mars Could Have Supported Life (Photos)]

More knowledge

Viking veteran Ben Clark, now a senior research scientist at the Space Science Institute in Boulder, Colorado, said "it's about time to start earnestly searching for signs of [Mars] life again."

Clark developed a Viking-carried instrument that measured the composition of Martian soils.

"From what we have learned since Viking about the past history of Mars, it was even more eminently suited for the origin of life than we knew when the search began," Clark said. "A Viking lesson learned is that you had better understand the environment well before designing tests for biological activity."

Astrobiologist Dirk Schulze-Makuch, a professor at the Technical University Berliny, also said the Viking life-detection experiments were conducted before scientists really understood the Red Planet.

"Life is intrinsically linked to its environment," Schulze-Makuch told Space.com. Not having that information in hand, we cannot home in on optimal search and life-detection strategies, and "that, of course, also applies to the icy moons," he added, referring to ocean-harboring worlds such as the Jupiter moon Europa and the Saturn satellite Enceladus.

"If it would have been known at the time of the Viking mission about Mars what is known today, they probably would have come up with the conclusion that microbial life likely exists on Mars," Schulze-Makuch said.

"I think the consensus is shifting more into the direction that the extraordinary claim would be that 'Mars is and was always lifeless,'" he added, referring to astronomer Carl Sagan's famous saying that "extraordinary claims need extraordinary evidence."

Nevertheless, Schulze-Makuch said that any declaration of life on Mars still requires overwhelming evidence before being scientifically saluted. "Just think about how long it took before it was accepted that there was and still is liquid water on Mars!" he said.

Better-informed instruments

John Rummel is familiar with Levin's steadfast life-on-Mars position.

"The Mars science community would have benefited greatly if Gil Levin had aspired to a leadership position in science after the Viking lander missions had completed their life-detection experiments," said Rummel, who twice served as NASA's planetary protection officer and is a former chair on planetary protection for the agency's Committee on Space Research.

New missions with better-informed instruments looking for life were possible then, Rummel said, but they needed a strong advocate who had the sort of data that Levin possessed.

"Fundamentally, there is nothing new about Mars that wasn't possible with Viking, but it is a long way from Chryse or Utopia [the two Viking landing spots on Mars in 1976] to the sub-polar-cap lake now claimed by the Italians," Rummel, who's now based at the SETI (Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence) Institute, told Space.com. "If Levin had stayed fully engaged, we might have already tried to go there."

Beyond the science debate

Astrobiologist Chris McKay, of NASA's Ames Research Center in Silicon Valley, is a longtime Mars investigator.

The science community is in general agreement, McKay said, that the Viking LR experiment did not detect life. The reactions noted by that instrument and the other results from Viking can be explained by reactive chemicals called perchlorates, he said.

Perchlorates were first detected in Martian soil by NASA's Phoenix lander in 2008, nearth the Red Planet's north pole. Further observations by other spacecraft strongly suggest that perchlorates are widespread throughout Mars.

That perchlorate explanation, however, is tentative, McKay said. "We cannot rule out that Gil Levin is correct and that there are dormant life-forms in the Martian soil," he said.

If so, that finding has implications beyond the science debated. "Are we confident enough that the Martian soil is lifeless to send astronauts … and then to bring those astronauts back to Earth? I say no," McKay said. "It seems to me that the standard of proof must be higher for these activities, and we have not reached that standard yet."

But McKay thinks Levin is right in continuing to insist that the possibility of life be considered.

"Life may not be the scientifically preferred explanation, but it cannot yet be disproven," McKay concluded.

Leonard David is author of "Mars: Our Future on the Red Planet," published by National Geographic. The book is a companion to the National Geographic Channel series "Mars." A longtime writer for Space.com, David has been reporting on the space industry for more than five decades. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. This version of the story published on Space.com.

Leonard David is an award-winning space journalist who has been reporting on space activities for more than 50 years. Currently writing as Space.com's Space Insider Columnist among his other projects, Leonard has authored numerous books on space exploration, Mars missions and more, with his latest being "Moon Rush: The New Space Race" published in 2019 by National Geographic. He also wrote "Mars: Our Future on the Red Planet" released in 2016 by National Geographic. Leonard has served as a correspondent for SpaceNews, Scientific American and Aerospace America for the AIAA. He has received many awards, including the first Ordway Award for Sustained Excellence in Spaceflight History in 2015 at the AAS Wernher von Braun Memorial Symposium. You can find out Leonard's latest project at his website and on Twitter.