Scientists behind controversial 2010 arsenic-based life study clap back as paper gets pulled: 'We do not support this retraction'

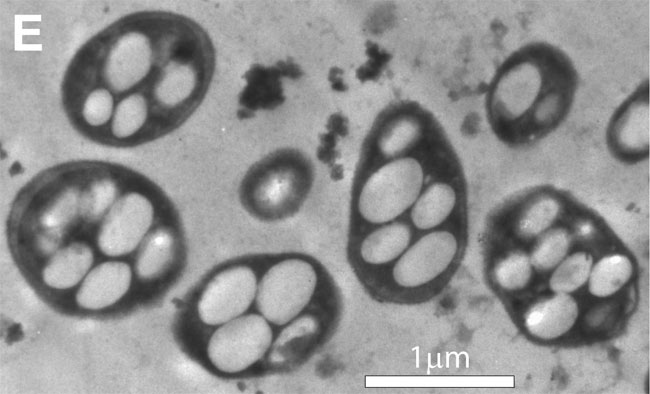

If the results had held up, the discovery of microbes that use arsenic instead of phosphorus in their biochemistry would have forever changed astrobiology.

The controversial claim of microbes that exhibit arsenic rather than phosphorus in their biochemistry has been retracted by the journal Science 15 years after it was first published — but while most in the research community are pleased by the decision, the retraction has angered the authors of the original study.

Arsenic, as we know from its use as a poison, is a toxic substance. Thus, life as we know it of course would not include arsenic in its biochemistry. Yet, because the search for alien life is, by its very definition, a search for life as we don't know it, astrobiologists like to consider the possibility of organisms that have a different biochemistry to the one we're familiar with.

This, in fact, led to NASA, — and with great razzamatazz, one might add — holding a press conference in 2010 that declared the supposed discovery of arsenic-based microbial life in Mono Lake, which is a heavily salt-rich body of water in California.

NASA claimed this discovery would forever change the search for life beyond Earth.

Life's chemical details

Consider that all life as we know it, including human life, exclusively uses six key elements in its biochemistry: carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, phosphorus, oxygen and sulfur.

Take phosphorus as an example. In our biochemistry, phosphorus, in the form of phosphate, is crucial for forming the sugar-phosphate backbone of molecules of RNA and DNA, as well as storing and delivering metabolic energy through adenosine triphosphate (ATP).

Astronomical observations, however, suggest phosphorus might not be evenly distributed across the Milky Way galaxy. And it has been posited that life in those phosphorus-depleted regions of space might survive by substituting phosphorus with another element, such as arsenic. It was this possibility that, 15 years ago, prompted a team led by Felisa Wolfe–Simon of NASA's Astrobiology Institute to search for possible arsenic-based life in the extreme alkaline conditions within Mono Lake.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Then, in that 2010 press conference, the discovery team revealed they had found it in the form of a bacterium known as GFAJ-1 present in supposedly phosphorus-free samples from Mono Lake. The discovery was hailed as a revolutionary development in astrobiology — for all of about five minutes.

Despite all the hullaballoo of the press conference, when Wolfe–Simon and her team's work was published online by the journal Science, other biochemists quickly came out to argue there were serious flaws in the research. Specifically, they argued that swapping out phosphorus for arsenic would cause DNA to dissolve within a second when exposed to water. More damning was the claim from the critics that the samples used by Wolfe–Simon's team were contaminated by phosphorus from the lake. The life in those samples, the critics argued, was probably still just using the phosphorus within those samples.

When Science finally published the research paper in print a year later, it was appended by eight technical comments from other researchers highly critical of the findings, plus two extra papers from independent teams who tried to replicate the results but failed to find any evidence for arsenic-based life in Mono Lake. Wolfe–Simon and her colleague also published a response to the criticisms, in which they wrote that "we maintain that our interpretation of As [arsenic] substitution, based on multiple congruent lines of evidence, is viable."

Not many people believed them, and Wolfe–Simon's team have never published the results of any follow-up experiments that try to address some of the points in the criticism; they also declined to respond to any criticism other than through the medium of peer-reviewed letters. The blowback against Wolfe–Simon's team was fierce and, at times, unsightly, with some abusive comments being leveled directly at Wolfe–Simon, who was still a young researcher. As a consequence, Wolfe–Simon opted to drop out of active research.

Now, 15 years later, Science's Editor-in-Chief Holden Thorp and the journal’s Executive Editor Valda Vinson have reopened the can of worms by deciding to retract the paper. Why has it taken so long for them to do so?

"Science did not retract the paper in 2012 because at that time, Retractions were reserved for the Editor-in-Chief to alert readers about data manipulation or for authors to provide information about post-publication issues," Science’s editors wrote in their official retraction notification. "Our decision then was based on the editors' view that there was no deliberate fraud or misconduct on the part of the authors. We maintain this view, but Science’s standards for retracting papers have expanded. If the editors determine that a paper's reported experiments do not support its key conclusions, even if no fraud or manipulation occurred, a Retraction is considered appropriate."

The other side of the story

Traditionally, papers were only retracted if evidence of fraud or misconduct came to light, or if a paper's authors requested that it be retracted, perhaps if new evidence disproved their results. However, the Retraction Watch website reports that, since 2019, Science has retracted 20 papers from its various publications, mostly on the basis of what the journal believes to be innocent errors.

Suffice to say, Wolfe–Simon and her team-members do not agree with Science's decision. In their response, published in the interests of fairness along with the retraction by Science, the team stated their disappointment.

"We do not support this retraction," they wrote. "While our work could have been written and discussed more carefully, we stand by the data as reported. These data were peer-reviewed, openly debated in the literature, and stimulated productive research."

Moreover, the team argues that Science's decision-making process was flawed and that it contravenes the guidelines of the Committee on Publication Ethics, or COPE. Those guidelines state that retraction is only warranted when there is clear evidence of major errors, the fabrication of data, or falsification that damages the reliability of a paper's findings.

"In going beyond COPE, the editors of Science explain that 'standards for retracting papers have expanded'," the team wrote. "We disagree with this standard, which extends beyond matters of research integrity. Disputes about the conclusions of papers, including how well they are supported by the available evidence, are a normal part of the process of science. Scientific understanding evolves through that process, often unexpectedly, sometimes over decades. Claims should be made, tested, challenged, and ultimately judged on the scientific merits by the scientific community itself."

Thorp and Vinson went further in a blog post on Science's website, where they were clearer on the reason for the retraction and arguing that COPE's guidelines allow them to retract the paper. "Given the evidence that the results were based on contamination, Science believes that the key conclusion of the paper is based on flawed data," they said.

The Retraction Watch website reports that Wolfe–Simon's team said that when they had been told about the retraction, they were not told that it was because of the claimed contamination. In fact, they only heard that from a second-hand source who had seen the blog post. Even so, contamination had been the number one criticism going all the way back to 2010, and was not a new or surprising accusation.

Thorp and Vinson ended their blog post by saying "we hope this decision brings the story to a close."

It remains to be seen whether this will be the case. However, what is clear is that there are serious lessons to be learned by both sides about how to present controversial results and how to both give and receive scientific criticism — Thorp and Vinson made a point in saying they condemn verbal abuse and ad hominem attacks that had been directed towards Wolfe–Simon and her team by other researchers. It also sheds light on the intricacies of when and how papers should be retracted.

In recent years, we have seen how claims of phosphine in the atmosphere of Venus and dimethyl sulphide, which is a potential biosignature, in the atmosphere of the exoplanet K2-18b have sparked debate and argument. It is to be hoped that scientists in the research community can remember to not take disagreements too far when debating these and other claimed discoveries in the future.

Keith Cooper is a freelance science journalist and editor in the United Kingdom, and has a degree in physics and astrophysics from the University of Manchester. He's the author of "The Contact Paradox: Challenging Our Assumptions in the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence" (Bloomsbury Sigma, 2020) and has written articles on astronomy, space, physics and astrobiology for a multitude of magazines and websites.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.