Bad news for alien life? Earth-size planets may be less common than we thought

"It raises the question: Just how common are Earth-sized planets?"

As many as 200 worlds beyond our solar system discovered by astronomers may be larger than estimated, which could influence the search for extraterrestrial life.

That's the theory of a team of researchers who looked at hundreds of extrasolar planets, or exoplanets, observed by NASA's Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS).

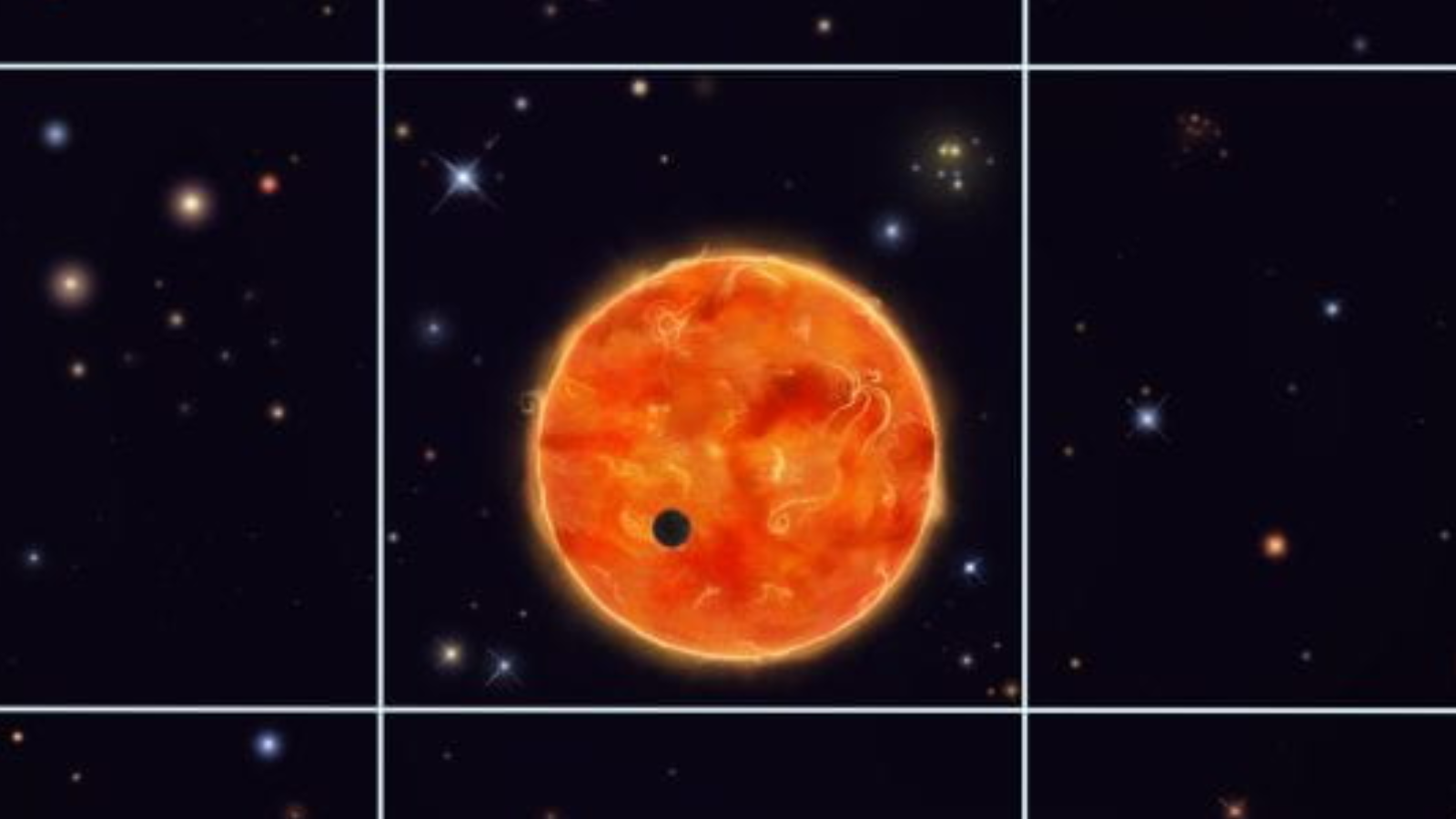

TESS hunts exoplanets by catching them as they cross the face of, or "transit," their parent star, which causes a tiny drop in light from that star. The study team discovered that light from stars neighboring the one being transited could "contaminate" TESS' data, making it look like the transiting planet is blocking less light than it actually is. And that would make the planet look smaller than it is.

"We found that hundreds of exoplanets are larger than they appear, and that shifts our understanding of exoplanets on a large scale," University of California, Irvine researcher and team leader Te Han said in a statement. "This means we may have actually found fewer Earth-like planets so far than we thought."

Exoplanets throw shade

Exoplanets are so distant and faint that it is only on rare occasions that astronomers can image them directly.

That means the transit method has become the most successful way of detecting worlds beyond the solar system. It requires the planet and its star to be at the right angle in relation to Earth, and for astronomers to wait for the planet to make two transits to confirm its existence.

The transit method is best at spotting short-period planets orbiting close to their host stars, because they make more frequent transits. The method also favors larger planets, which block more light.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"We’re basically measuring the shadow of the planet," said team member and UC Irvine astronomer Paul Robertson.

The team gathered hundreds of TESS observations of exoplanets, sorting them by the width of the exoplanets in question.

They then used computer modeling and data from the European Space Agency's (ESA) star-tracking mission Gaia to estimate how much light contamination TESS is experiencing during its observations.

"TESS data are contaminated, which Te's custom model corrects better than anyone else in the field," said Robertson. "What we find in this study is that these planets may systematically be larger than we initially thought. It raises the question: Just how common are Earth-sized planets?"

Move over Earth-like worlds: ocean planets could be more common

Because of the biases of the transit method mentioned above, the number of exoplanets detected with TESS having sizes and compositions similar to those of Earth was already low.

"Of the single-planet systems discovered by TESS so far, only three were thought to be similar to Earth in their composition," Han explained. "With this new finding, all of them are actually bigger than we thought."

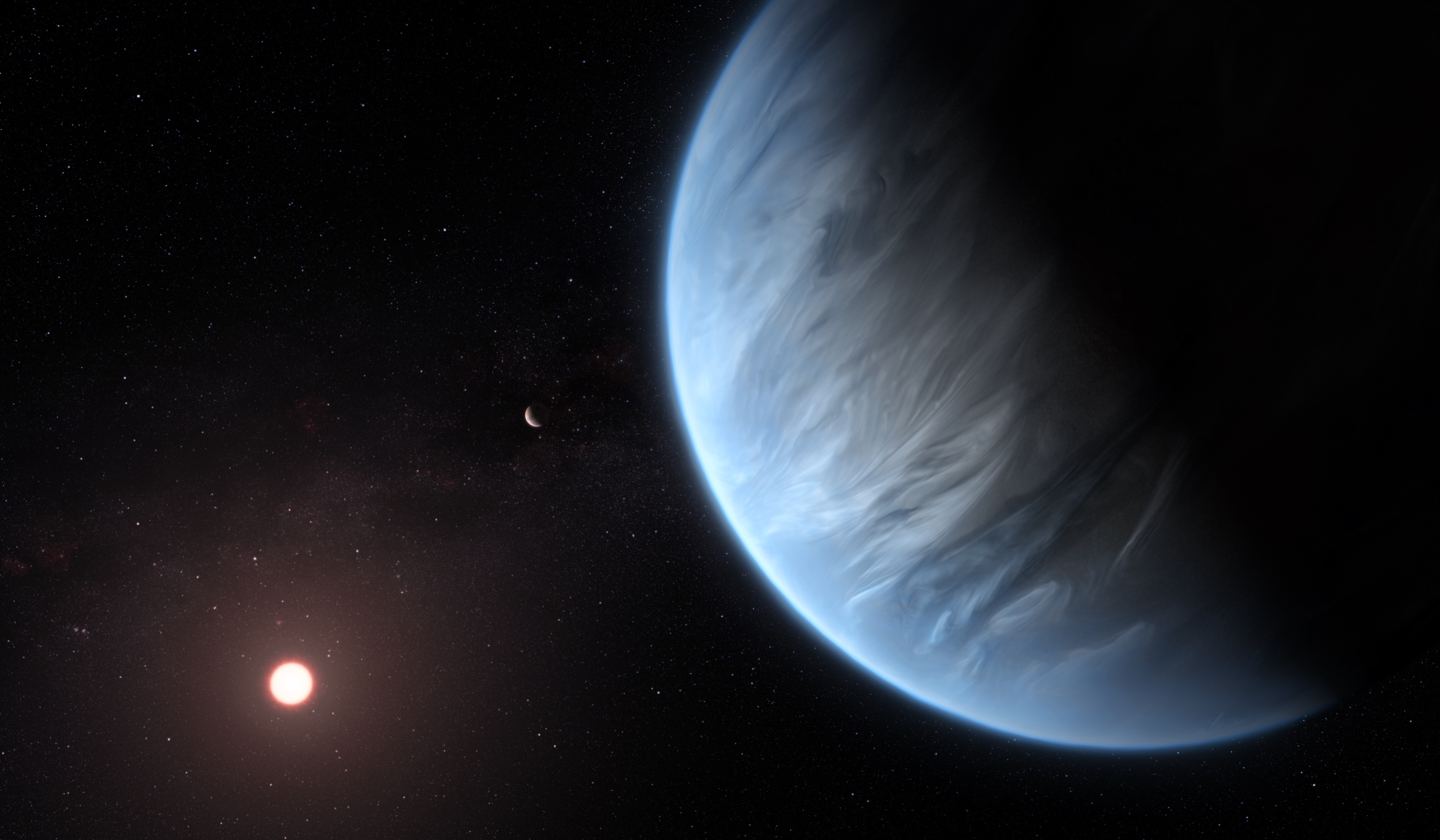

The likely outcome of this is that those exoplanets are larger ocean planets or "hycean worlds" covered by a large single ocean. Those worlds could also be gas giants smaller than Jupiter, like Neptune and Uranus.

That impacts the search for life because, though hycean worlds are packed with water, they could be lacking other ingredients needed for life to arise.

"This has important implications for our understanding of exoplanets, including, among other things, prioritization for follow-up observations with the James Webb Space Telescope, and the controversial existence of a galactic population of water worlds," Roberston added.

The next step for Han, Roberston, and colleagues is to re-examine planets previously deemed uninhabitable due to their size, to see if they are larger than previously thought.

In the meantime, the research is a reminder to astronomers to be cautious when assessing TESS data.

The team's research was published on Monday (July 14) in the Astrophysical Journal Letters.

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. whose articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space, Newsweek and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University. Follow him on Twitter @sciencef1rst.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.