Is the bar higher for scientific claims of alien life?

The skepticism and debate around the question of "are we alone in the universe" makes the field of astrobiology more cautious

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

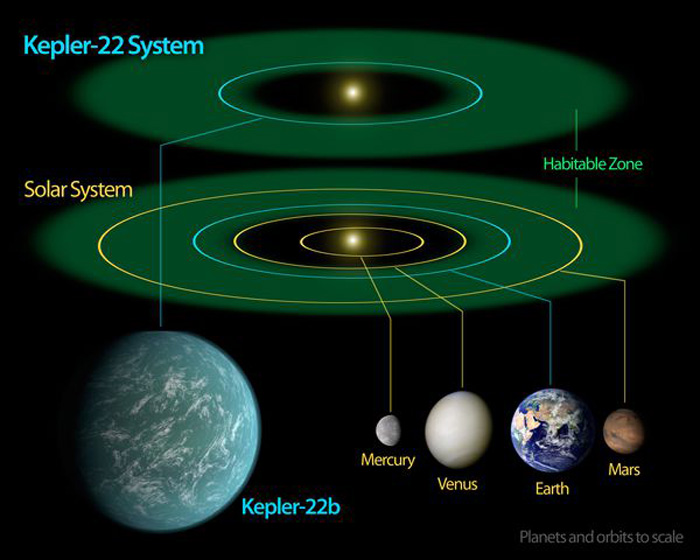

The search for extraterrestrial life has long gone back and forth between scientific curiosity, public fascination and outright skepticism. Recently, scientists claimed the “strongest evidence” of life on a distant exoplanet – a world outside our solar system.

Grandiose headlines often promise proof that we are not alone, but scientists remain cautious. Is this caution unique to the field of astrobiology? In truth, major scientific breakthroughs are rarely accepted quickly.

Newton’s laws of motion and gravity, Wegener’s theory of plate tectonics, and human-made climate change all faced prolonged scrutiny before achieving consensus.

But does the nature of the search for extraterrestrial life mean that extraordinary claims require even more extraordinary evidence? We’ve seen groundbreaking evidence in this search beforehand, from claims of biosignatures (potential signs of life) in Venus’s atmosphere to NASA rovers finding “leopard spots” – a potential sign of past microbial activity – in a Martian rock.

Both stories generated a public buzz around the idea that we might be one step closer to finding alien life. But on further inspection, abiotic (non-biological) processes or false detection became more likely explanations.

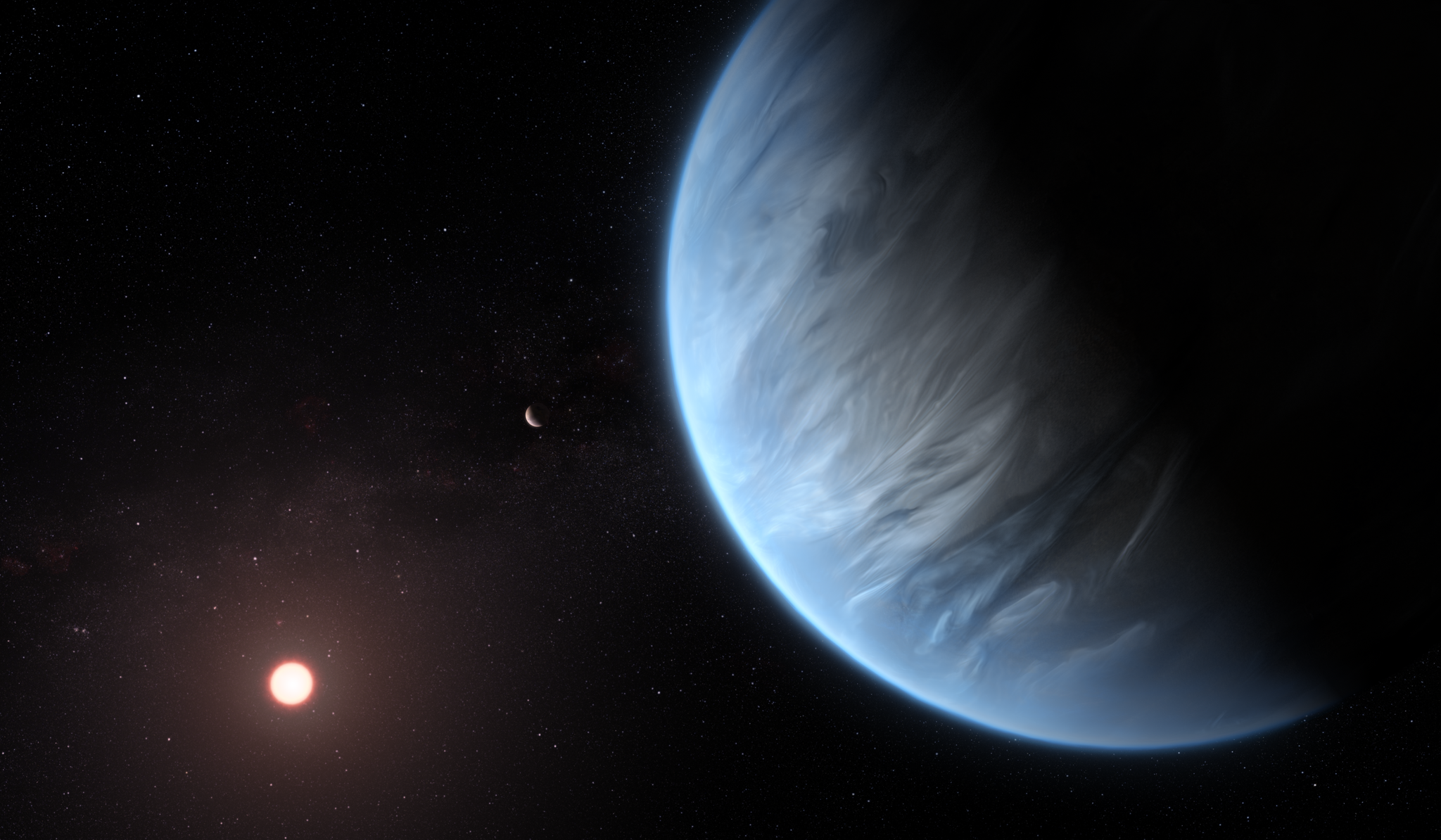

In the case of the exoplanet, K2-18 b, scientists working with data from the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) announced the detection of gases in the planet’s atmosphere – methane, carbon dioxide, and more importantly, two compounds called dimethyl sulphide (DMS) and dimethyl disulphide (DMDS). As far as we know, on Earth, DMS/DMDS are produced exclusively by living organisms.

Their presence, if accurately confirmed in abundance, would suggest microbial life. The researchers even suggest there’s a 99.4% probability that the detection of these compounds wasn’t a fluke – a figure that, with repeat observations, could reach the gold standard for statistical certainty in the sciences. This is a figure known as five sigma, which equates to about a one in a million chance that the findings are a fluke.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

So why hasn’t the scientific community declared this the discovery of alien life? The answer lies in the difference between detection and attribution, and in the nature of evidence itself.

JWST doesn’t directly “see” molecules. Instead, it measures the way that light passes through or bounces off a planet’s atmosphere. Different molecules absorb light in different ways, and by analysing these absorption patterns – called spectra – scientists infer what chemicals are likely to be present. This is an impressive and sophisticated method – but also an imperfect one.

It relies on complex models that assume we understand the biological reactions and atmospheric conditions of a planet 120 light years away. The spectra suggesting the existence of DMS/DMDS may be detected because you cannot explain the spectrum without the molecule you’ve predicted, but it could also result from an undiscovered or misunderstood molecule instead.

Climate comparison

Given how momentous the conclusive discovery of extraterrestrial life would be, these assumptions mean that many scientists err on the side of caution. But is this the same for other kinds of science? Let’s compare with another scientific breakthrough: the detection and attribution of human-made climate change.

The relationship between temperature and increases in CO₂ was first observed by the Swedish scientist Svante Arrhenius in 1927. It was only taken seriously once we began to routinely measure temperature increases. But our atmosphere has many processes that feed CO₂ in and out, many of which are natural.

So the relationship between atmospheric CO₂ and temperature may have been validated, but the attribution still needed to follow.

Carbon has three so-called flavors, known as isotopes. One of these isotopes, carbon-14, is radioactive and decays slowly. When scientists observed an increase in atmospheric carbon dioxide but a low volume of carbon-14, they could deduce that the carbon was very old – too old to have any carbon-14. Fossil fuels – coal, oil and natural gas – are composed of ancient carbon and thus are devoid of carbon-14.

So the attribution of anthropogenic climate change was proven beyond reasonable doubt, with 97% acceptance among scientists. In the search for extraterrestrial life, much like climate change, there is a detection and attribution phase, which requires the robust testing of hypotheses and also rigorous scrutiny.

In the case of climate change, we had in situ observations from many sources. This means roughly that we could observe these sources close up. The search for extraterrestrial life relies on repeated observations from the same sensors that are far away. In such situations, systematic errors are more costly.

Further to this, both the chemistry of atmospheric climate change and fossil fuel emissions were validated with atmospheric tests under lab conditions from 1927 onwards. Much of the data we see touted as evidence for extraterrestrial life comes from light years away, via one instrument, and without any in situ samples.

The search for extraterrestrial life is not held to a higher standard of scientific rigor but it is constrained by an inability to independently detect and attribute multiple lines of evidence.

For now, the claims about K2-18 b remain compelling but inconclusive.

That doesn’t mean we aren’t making progress. Each new observation adds to a growing body of knowledge about the universe and our place in it. The search continues – not because we’re too cautious, but because we are rightly so.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Oliver "Ollie" Swainston (He/Him) is a research assistant at RAND Europe in the Science and Emerging Technologies team. His primary focus is civil space policy, with interests in both defense and energy & environment. Swainston specializes in earth observation technologies, geospatial visualization, and quantitative data analysis. His background is highly interdisciplinary with a Master of Space Studies degree from the International Space University alongside an M.Sc. in climate change and international development.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.