A city on the moon: Why SpaceX shifted its focus away from Mars

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Elon Musk has always been locked in on Mars.

The world's richest man has repeatedly said that he founded SpaceX back in 2002 primarily to help settle the Red Planet. Indeed, the company's website places Mars front and center, explaining why the fourth rock from the sun is the best target for human exploration and expansion.

Musk has generally been dismissive of our other off-Earth option, the moon. Just 13 months ago, for example, he stressed that SpaceX will go "straight to Mars," declaring Earth's natural satellite "a distraction."

Article continues belowBut over the weekend, Musk threw us a curveball, announcing that SpaceX is now centering its settlement plans on the moon — at least in the short term.

"For those unaware, SpaceX has already shifted focus to building a self-growing city on the moon, as we can potentially achieve that in less than 10 years, whereas Mars would take 20+ years," the billionaire wrote on Sunday afternoon (Feb. 8) via X, the social media platform he bought in 2022.

"The mission of SpaceX remains the same: extend consciousness and life as we know it to the stars," he added. "It is only possible to travel to Mars when the planets align every 26 months (six month trip time), whereas we can launch to the moon every 10 days (2 day trip time). This means we can iterate much faster to complete a moon city than a Mars city."

Must hinted at this shift last week, in a lengthy update detailing SpaceX's plans to operate a million-strong constellation of data-center satellites in Earth orbit.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

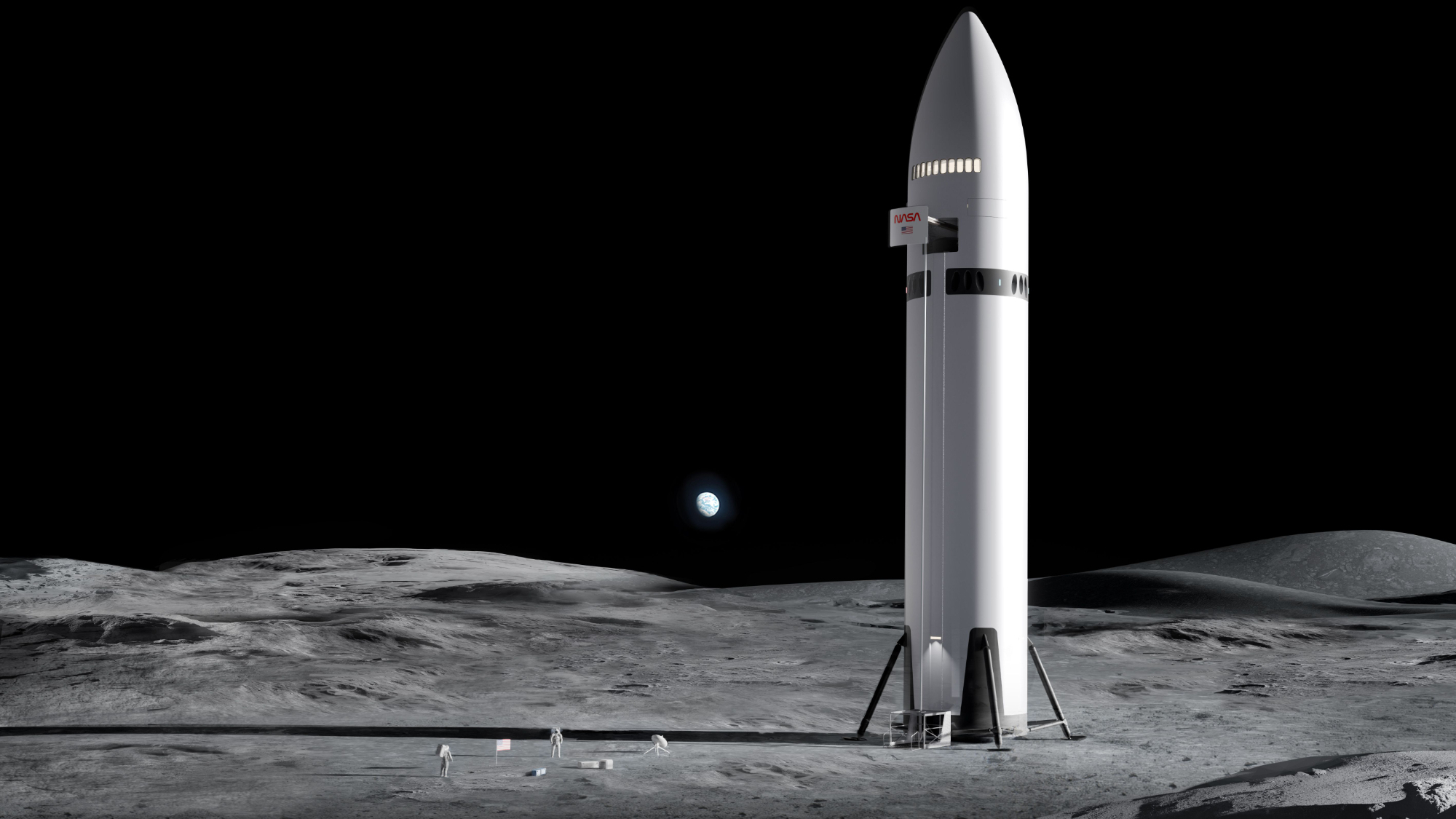

The vehicle that will launch all of these satellites is Starship, the fully reusable megarocket that SpaceX has been developing to achieve its off-Earth settlement goals. In that Feb. 2 update, Musk stressed Starship's lunar potential.

"Thanks to advancements like in-space propellant transfer, Starship will be capable of landing massive amounts of cargo on the moon," he wrote.

"Once there, it will be possible to establish a permanent presence for scientific and manufacturing pursuits," Musk added. "Factories on the moon can take advantage of lunar resources to manufacture satellites and deploy them further into space. By using an electromagnetic mass driver and lunar manufacturing, it is possible to put 500 to 1000 [terawatts]/year of AI satellites into deep space, meaningfully ascend the Kardashev scale and harness a non-trivial percentage of the sun's power."

(The Kardashev scale, named after the Soviet scientist who came up with it in 1964, classifies civilizations based on the amount of energy they can control. A Type I civilization can harness all of its home planet's power; a Type II can exploit the entirety of its star's energy, via a Dyson sphere or other such structure; and a Type III has its entire galaxy's output at its fingertips. Humanity has not even made it to Type I yet.)

But the off-Earth data-center aspect is a mere "bonus element" of the new moon-focused strategy, Elon Musk stressed in an X post on Monday (Feb. 9).

"The priority shift is because I'm worried that a natural or manmade catastrophe stops the resupply ships coming from Earth, causing the colony to die out," he wrote. "We can make the moon city self-growing in less than 10 years, but Mars will take 20+ years due to the 26-month iteration cycle. That is what matters most."

And SpaceX hasn't given up on Mars settlement. In other X posts over the past few days, Musk has emphasized that the new plan just pushes the timeline back a bit.

"Mars will start in 5 or 6 years, so will be done in parallel with the moon, but the moon will be the initial focus," he wrote on Monday morning. In another recent post, he said that a crewed Mars flight could happen in 2031.

Starship Die Cast Rocket Model Now $47.99 on Amazon.

If you can't see SpaceX's Starship in person, you can score a model of your own. Standing at 13.77 inches (35 cm), this is a 1:375 ratio of SpaceX's Starship as a desktop model. The materials here are alloy steel and it weighs just 225g.

While the settlement focus on the moon is new, SpaceX has been working toward a crewed lunar mission for about five years now. In April 2021, NASA announced that it had selected Starship to be the first crewed lander for its Artemis program, which aims to establish a permanent, sustained human presence on and around the moon by 2030 or so.

If all goes according to plan, Starship will deliver astronauts to the lunar surface for the first time on the Artemis 3 mission, which is currently expected to launch in 2028. But that timeline assumes success on Artemis 2, which will launch four people around the moon and back to Earth as soon as next month.

It also assumes that Starship will be ready, which certainly cannot be taken for granted. The giant rocket has flown 11 test flights to date, all of them suborbital, so there are a lot of development boxes left to check.

Starship still needs to ace an orbital mission, for example, and show that it can be refueled off Earth. (Each Starship lunar mission will require multiple "tanker" flights — perhaps 10 or 12 of them — to fill the vehicle with propellant for the long journey to the moon.)

Last fall, then-NASA Acting Administrator Sean Duffy voiced concern with the pace of Starship's development, announcing that he planned to open SpaceX's moon-landing contract up to competition from other companies, such as Jeff Bezos' Blue Origin.

That threat may have died down, given that Duffy no longer leads NASA; billionaire tech entrepreneur Jared Isaacman, who has flown to Earth orbit twice with SpaceX, is now the agency's chief. But competition is still very much in the air; Blue Origin recently announced that it's pausing its suborbital space tourism flights for at least two years to work on getting humans to the moon.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.