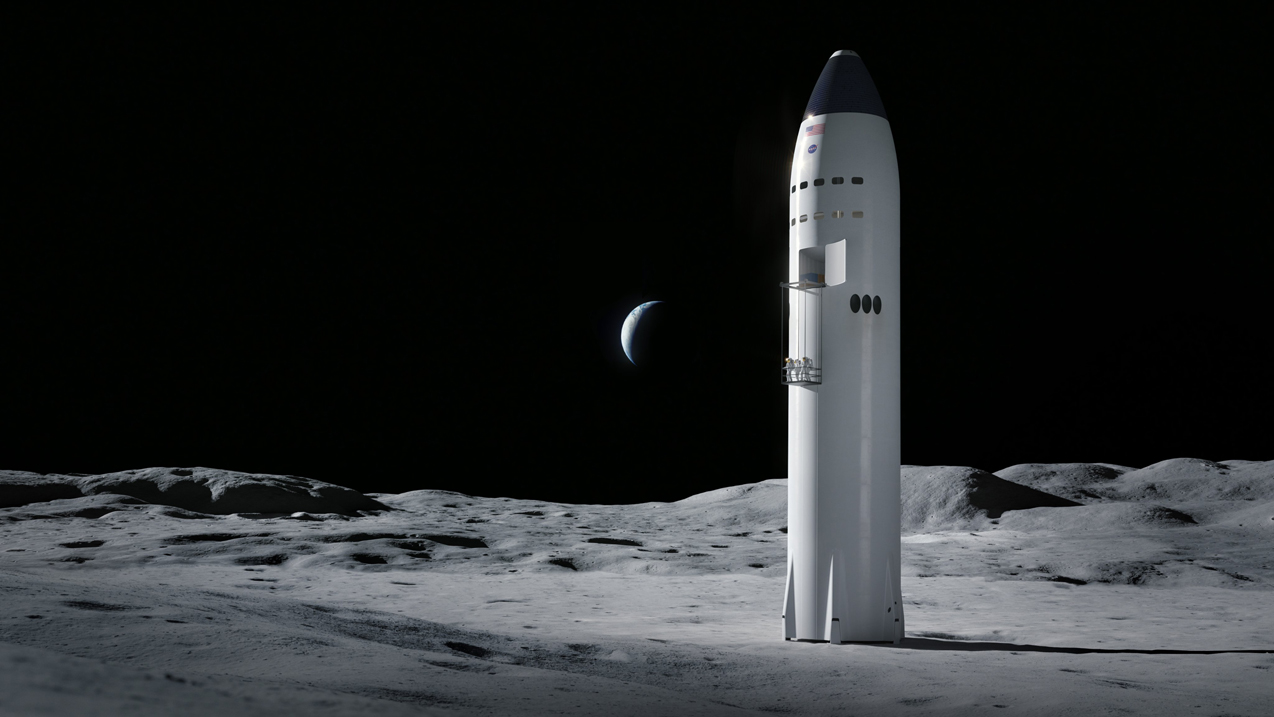

Starship and Super Heavy: SpaceX's deep-space transportation for the moon and Mars

SpaceX and Super Heavy are tasked with landing astronauts on the moon and flying paying customers around it.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

Starship and Super Heavy are the biggest, most important pieces of Elon Musk's grand plan for SpaceX, his private spaceflight company. SpaceX's short-term aims are to supply cargo and astronauts for the International Space Station; provide transportation and seats for private customers, like Axiom Space or billionaire Jared Isaacman's Inspiration4; and fly Starlink satellites and payloads for other customers aboard its Falcon 9 or Falcon Heavy rockets. But the revenues flowing in from these projects are raising funds for Musk's larger goal of moving deep into space.

Musk has repeatedly stressed that he founded SpaceX back in 2002 primarily to help humanity colonize Mars. It's vital that we become a multiplanet species, the billionaire entrepreneur has said, citing both a much-reduced probability of extinction and the thrill that meaningful space exploration will deliver to billions of people around the world. Critics say we should instead be focusing on climate change and other issues on Earth.

In photos: SpaceX's Starship and Super Heavy rocket

SpaceX is now actively trying to turn this sci-fi dream into reality. The company is developing a 100-passenger spaceship called Starship and a giant rocket known as Super Heavy, which together constitutes the transportation system that Musk thinks will bring Mars settlement within reach at long last.

"This is the fastest path to a self-sustaining city on Mars," Musk said in September 2019 during a webcast update about the Starship-Super Heavy architecture.

While the spaceship has yet to achieve orbit, it has already attracted lucrative contracts from Isaacman's Polaris Program, Japanese venture dearMoon to fly eight artists and a billionaire around the moon, seats for billionaire Dennis Tito and wife Akiko on another moon mission, and at least two landing missions for NASA's Artemis moon program.

The original vision

Starship first came to light, under another moniker, during a 2016 presentation by Musk, in which he laid out the basic idea for this so-called Interplanetary Transport System: a large spacecraft and a huge rocket, both of which would be completely and rapidly reusable.

The rocket would launch the spacecraft into Earth orbit and then come back down to Earth for a vertical, propulsive landing. (The name was new; Musk previously referred to his envisioned concept, though much more vaguely, as the Mars Colonial Transporter. He also referred to this system as the Big Falcon Rocket, although now it's more simply called Starship.)

The spaceship, meanwhile, would make its own way from Earth orbit to Mars (or the moon, or any other desired destination). Musk said the craft will eventually touch down on such alien worlds and take off from them as well, without the need for any additional landing craft or ascent vehicles. (The separate rocket is needed just to get out of Earth's substantial gravity well.)

Off-Earth refueling of the ship is, therefore, key to Musk's vision. For example, spacecraft coming home from Mars or the moon will need to be topped up on those worlds, using locally produced propellant.

Both vehicles will be powered by SpaceX's next-generation Raptor engine, which is more powerful than the Merlin engine that propels the company's Falcon 9 and Falcon Heavy rockets.

Related: See stunning photos of SpaceX Falcon Heavy's first night launch

The ultimate plan involves sending 1,000 or more people-packed spaceships to Mars every 26 months, helping to establish a million-person city on the Red Planet within 50 to 100 years, Musk said. (Earth and Mars align favorably for interplanetary missions just once every 26 months.)

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Related: How long does it take to get to Mars?

Musk did not lay out plans for building this city. That will happen organically as more and more people arrive on Mars, he said, like the transcontinental railroad that helped open the American West to settlement from the East and Midwest in the 19th century.

And these pioneers won't just be the super-rich if all goes according to plan. The system's reusability could eventually bring the price of a Mars trip down enough to make it affordable for large numbers of people, Musk said.

Starship development

The system is now called Starship and the huge rocket is now called Super Heavy.

At first, SpaceX still planned to build the Starship vehicle out of carbon fiber. But in January 2019, Musk announced that he was switching to stainless steel. Steel is a bit heavier than carbon fiber but has great thermal properties and is far, far cheaper, Musk said. He has since called the material switch the best design decision yet made on the project.

In May 2019, Musk said the current plan calls for six Raptors on the Starship vehicle rather than seven. And a few months later, he tweeted that Super Heavy will now sport 35 Raptors instead of 31.

That brings us to the last substantial design update before test flights, which Musk presented on Sept. 28, 2019, from SpaceX's South Texas facility, near the tiny village of Boca Chica. The billionaire didn't announce any huge changes, though there was some more engine news: Super Heavy will now have space for 37 Raptors, though not all of those slots will be filled on every flight. Each mission will probably require at least 24 Raptors on the booster, Musk said, and prototypes these days typically fly 33.

Musk had previously estimated the total development cost of the Starship project to be between $2 billion and $10 billion. On Sept. 28, 2019, he said the price tag for SpaceX would be toward the lower end of that range — "probably closer to two or three [billion] than it is to 10 [billion]," Musk told CNN Business during an interview shortly after the design update.

Test flights underway

Starship has flown half a dozen times in hops or high-altitude flights, while a small test system called Starhopper to examine the Starship concept achieved two brief, untethered test flights at Boca Chica before being retired in late August 2019. Starship's next major milestone is a flight in Earth orbit, but SpaceX is awaiting approval on its plan to manage environmental concerns at Starbase, the facility in south Texas where Starship is launched.

The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) has been reviewing public feedback, speaking with other government agencies and then assessing SpaceX's progress on 75 action items of a programmatic environmental assessment. All told, SpaceX has not made any flights of Starship since May 2021, although it does do engine firings frequently on Starship and Super Heavy at Starbase.

Musk's first version of Starship was an eye-catching, 165-foot-tall (50 m) Starship prototype called the Mk1. It was supposed to be used for a test flight but exploded during pressure testing in November 2019.

Version Mk2 was worked on but never completed, while Mk3 was renamed to SN1 in December 2019. SpaceX then did a series of ambitious ground tests to assess how much punishment its versions could stand up to, which, in part, led to a series of Starship versions blowing up during testing. SN1 was destroyed during pressurization tests in February 2020. Version SN2 has been tested and decommissioned (still intact), although both SN3 and SN4 were destroyed in other tests in April and May 2020, respectively.

SN5 was the first to fly, achieving a brief hop to about 500 feet (150 m) on Aug. 4, 2020; SN6 finished its own similar hop on Sept. 3. Both prototypes were decommissioned in early 2021.

Then came the high-altitude test flights, often involving a series of flips, twists and other aerial maneuvers that sometimes tested the vehicles beyond their limits. SN8 was destroyed after impact during a 7.7-mile (12.5 km) altitude test on Dec. 9, 2020. Next, SN9 flew to more than 6 miles (10 km) before crashing into the landing pad on Feb. 2, 2021. SN10 did make a soft landing after its own 6-mile flight on March 3, 2021, but exploded eight minutes later, likely due to helium being ingested unexpectedly.

Skipping a few serial numbers in terms of flights (SN12 through SN14 never flew), SN15 was next to take to the air. SN15 was armed with improvements in avionics, Raptor engines and overall structure. It even sported a Starlink antenna on the side, a first for Starship. This version was the first to achieve a soft touchdown, which it did on May 5, 2021, following a 6-mile flight, and it even survived a small fire post-landing.

Starship's first orbital launch on April 20, 2023, ended with a dramatic explosion. The first-ever integrated Starship rocket lifted off from SpaceX's Starbase facility at Boca Chica Beach on South Texas' Gulf Coast at 9:33 a.m. EDT (1333 GMT; 8:33 a.m. local Texas time), powered by its 33 first-stage Raptor engines. But approximately three minutes after liftoff the upper stage failed to separate from the Super Heavy First Stage. The two vehicles remained connected, and the stack began to tumble, ultimately exploding — or experiencing a "rapid unscheduled disassembly," as SpaceX terms it — just under four minutes after launch.

Related: Every SpaceX Starship explosion and what Elon Musk and his team learned from them (video)

As for flying people, presumably, the first to fly on Starship would be the astronauts for NASA's Artemis 3 mission, which the agency aims to launch for a touchdown on the moon in 2025. SpaceX received a sole-source contract for the Artemis Human Landing System in April 2021, but following protests and a lawsuit from other contenders, all of which were overturned, the U.S. Senate directed NASA to find a second company. A second vendor will likely be chosen in 2023.

Other flights using Starship with Isaacman, Tito and dearMoon do not have firm dates at this time. There's a fair amount of work to do in the interim, of course. For example, there's the issue of keeping Starship's passengers happy and healthy during their flights to the moon, Mars and beyond.

We know little about Starship's life-support system. But Musk said during the September 2019 update that he envisions a "regenerative" system, which recycles water vapor and carbon dioxide, processing this latter gas to provide oxygen. And he doesn't think implementing this tech will be all that difficult.

"I don't think it's actually superhard to do that," he said. "Relative to the spacecraft itself, the life-support system is pretty straightforward."

Musk is famous for his "aspirational" timelines, so the above target dates are far from set in stone and will depend upon regulation, testing and other matters. Testing big spacecraft takes time and patience, but revenues are flowing in now for future flights, which indicates at least some community confidence in Starship flying people in the mid-2020s or early 2030s.

Additional resources

Go up the rocket-catching tower for Starship with Everyday Astronaut. Watch the operations of Starbase 24 hours a day, seven days a week with NASA Spaceflight. Follow the latest Starship updates at SpaceX.

Bibliograhy

dearMoon Project. (2022.) https://dearmoon.earth/

NASA. (2021, April 16). As Artemis moves forward, NASA picks SpaceX to land next Americans on moon. https://www.nasa.gov/press-release/as-artemis-moves-forward-nasa-picks-spacex-to-land-next-americans-on-moon

NASA. (2022, Nov. 15.) https://www.nasa.gov/press-release/nasa-awards-spacex-second-contract-option-for-artemis-moon-landing-0

SpaceX. (2022.) Starship. https://www.spacex.com/vehicles/starship/

SpaceX. (2022, Oct. 12.) "First crewmembers of Starship's second commercial spaceflight around the moon." https://www.spacex.com/updates/#starship-second-moon-flight

Mike Wall's book about the search for alien life, "Out There" (Grand Central Publishing, 2018; illustrated by Karl Tate), is out now. Follow him on Twitter @michaeldwall.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.

- Elizabeth HowellContributing Writer