Super-Earth exoplanets may have built-in magnetic protection from churning magma — and that's good news for life

"A strong magnetic field is very important for life on a planet."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

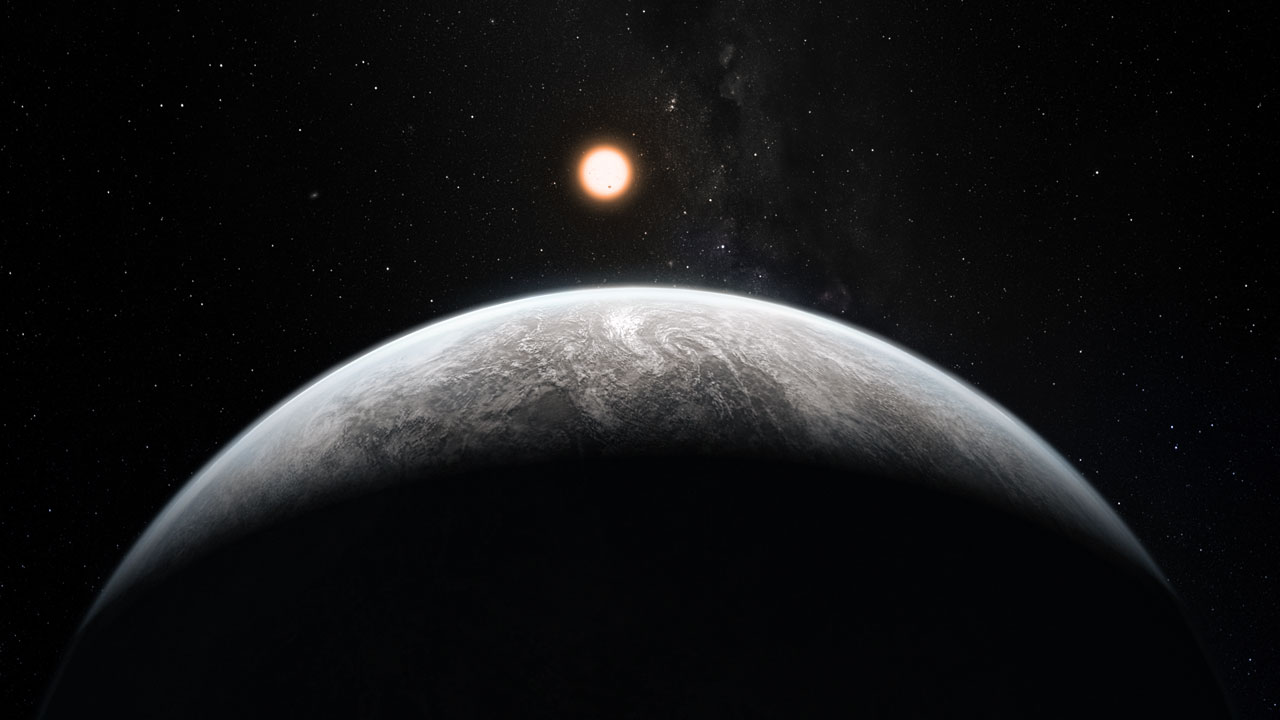

"Super-Earth" exoplanets may have an in-built way to protect themselves from harmful radiation, giving any potential life on such worlds a better chance of surviving, according to recent research.

Super-Earths, worlds larger than Earth but smaller than Neptune, are among the most commonly detected types of extrasolar planets, or exoplanets, in the Milky Way. Because many have been found within their stars' habitable zones — regions where liquid water could exist and, thus, potentially support life — scientists have increasingly focused on whether these planets can sustain life-friendly conditions over billions of years.

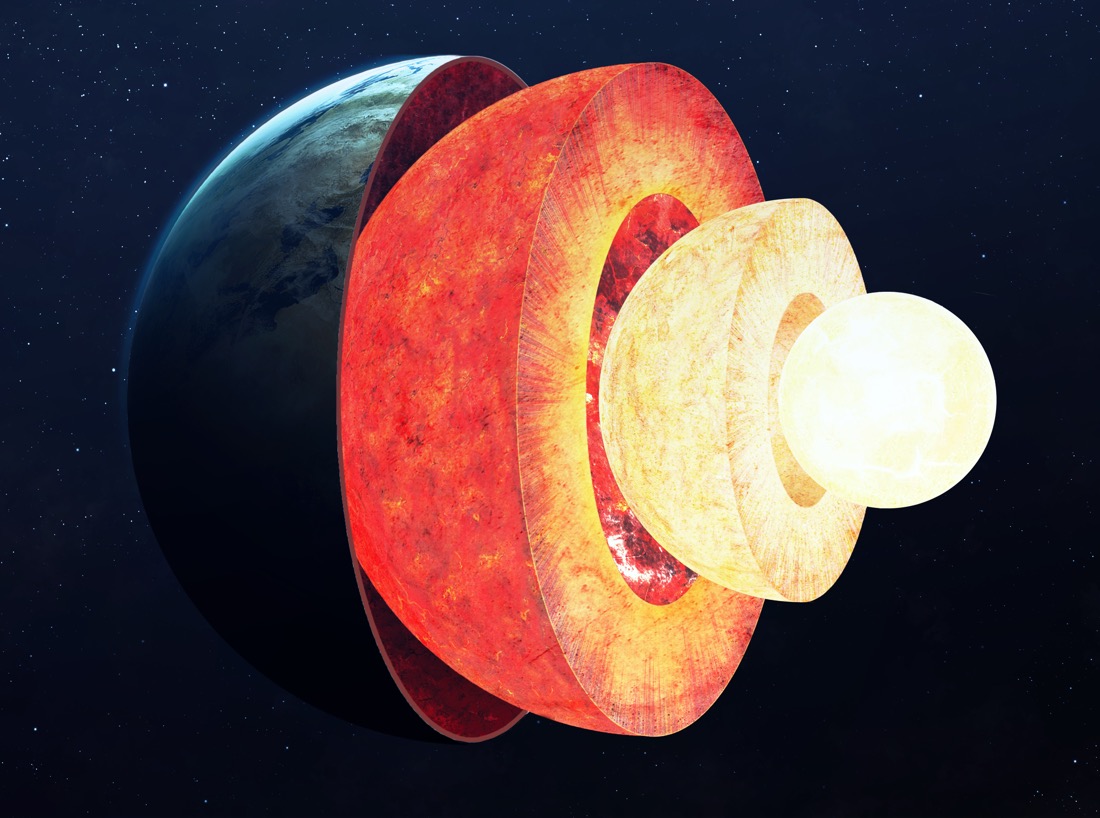

The new study suggests that many super-Earths may be able to generate powerful magnetic fields from molten rock not in their cores, like Earth does, but in a layer sandwiched between the core and mantle.

"A strong magnetic field is very important for life on a planet," study lead Miki Nakajima, an associate professor in the department of Earth and environmental sciences at the University of Rochester in New York, said in a statement. "Super-earths can produce dynamos in their core and/or magma, which can increase their planetary habitability."

The findings, published Jan. 15 in the journal Nature Astronomy, help resolve a long-standing puzzle about how super-Earths might maintain magnetic fields despite interiors whose structures differ from Earth's, the researchers say.

"This paper suggests that, like in many other things, exoplanets might not necessarily follow the solar system paradigm concerning magnetic field generation," Luca Maltagliati, a senior editor at Nature Astronomy, who was not involved with the new study, wrote in a brief piece summarizing the findings. "Planets with masses 3-6 times that of Earth might have their main magnetic field engine not in the core like the Earth but in a layer between the core and mantle."

Long-lived magnetic shields are considered essential for habitability because they help prevent planetary atmospheres from being stripped away by stellar winds and protect surfaces from harmful cosmic and stellar radiation.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Without such protection, even planets located in otherwise favorable habitable zones may struggle to maintain the conditions needed for life, meaning such magma-driven magnetic fields could play a crucial role in making super-Earths habitable across the galaxy.

Earth's magnetic field, which has operated for more than 3 billion years, is generated by the movement of liquid iron in the outer core surrounding a solid inner core. That inner core is critical because it releases heat and lighter elements that keep the molten outer core moving, allowing our planet to sustain its magnetic field.

But larger rocky worlds such as super-Earths are thought to have cores that are either fully solid or fully liquid, which typically limit the operation of a conventional, Earth-like core dynamo.

Nakajima and her team point to an alternative mechanism known as a basal magma ocean (BMO), a layer of molten rock that forms between the core and the mantle. Such layers are thought to arise during planet formation, according to the new study, when repeated large impacts generate global magma oceans that partially crystallize and concentrate iron-rich melt at depth.

The idea of a BMO-driven dynamo was first proposed as a way to explain how Earth may have generated a magnetic field early in its history, before its inner core had formed. Such a layer would have formed following the moon-forming impact, but it likely solidified after roughly 1 billion years, the new study notes.

Super-Earths, by contrast, are larger and experience much higher internal pressures, conditions that could allow basal magma oceans to persist for far longer and sustain magnetic fields over billions of years, the researchers say.

To test whether these deep magma layers could generate magnetic fields, Nakajima and her team conducted shock experiments that compressed rock-forming materials to the extreme pressures expected inside planets several times more massive than Earth. The researchers then combined the lab results with planetary models to determine how massive a super-Earth must be to generate a magnetic field.

They found that under such crushing pressures, iron-rich magma becomes metallic and electrically conductive, suggesting that super-Earths roughly three to six times Earth's mass could maintain BMO-driven magnetic fields for several billion years, longer, and potentially stronger than magnetic fields generated by Earth-like metallic cores alone.

In some cases, the resulting magnetic field at the planet's surface could rival or even exceed Earth's, according to the statement.

"Although detecting the magnetic fields of exoplanets remains challenging," the researchers wrote in the briefing, "it might be possible to observe such strong BMO-driven dynamos in future observations."

Sharmila Kuthunur is an independent space journalist based in Bengaluru, India. Her work has also appeared in Scientific American, Science, Astronomy and Live Science, among other publications. She holds a master's degree in journalism from Northeastern University in Boston.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.