How to make a super-Earth: The universe's most common planets are whittled down by stellar radiation

"What's so exciting is that we're seeing a preview of what will become a very normal planetary system."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

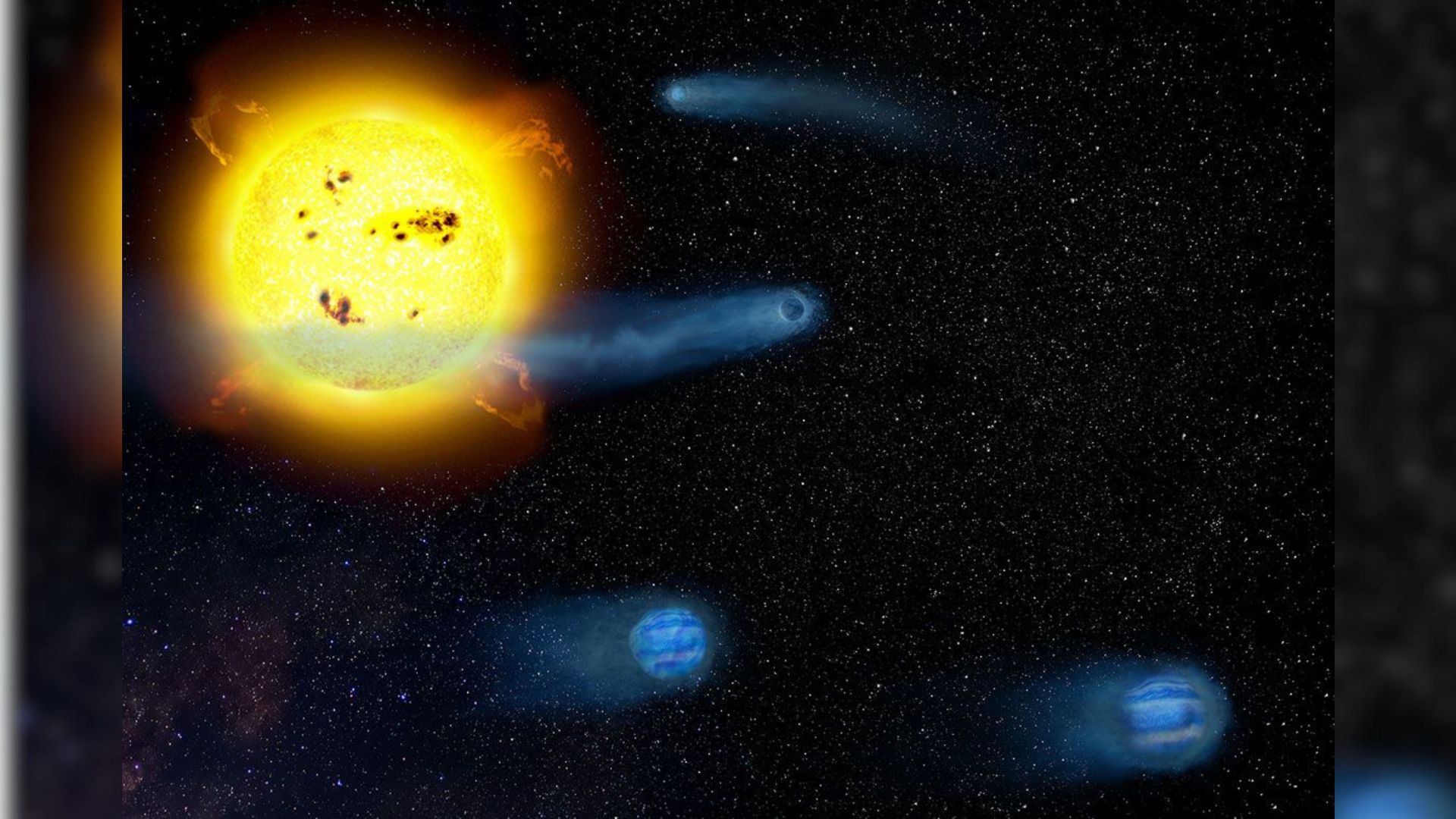

The secret behind the formation of super-Earth and sub-Neptune exoplanets has been revealed, thanks to a study of four young planets that are evaporating.

Some 350 light-years away, the V1298 Tau system features an infant sun-like star, just 23 million years old, orbited by four planets on compact orbits close to their star, and all of which are seen to transit. Discovered in 2019 by astronomers Erik Petigura of the University of California, Los Angeles and Trevor David of the Flatiron Institute in New York, using data from the Kepler space telescope's K2 mission, the four planets are huge, with radii between five and 10 times that of Earth.

Now, a team of astronomers led by John Livingston from the Astrobiology Center in Tokyo and including Petigura and David, have used "transit timing variations" to measure the mass of each of the four planets. This has allowed the researchers to determine that the planets are very low density and that the atmosphere of each world is photoevaporating into space. This, says Livingston's team, is the key to the formation of super-Earths and sub-Neptunes.

Super-Earths are rocky planets larger and more massive than our own planet. Sub-Neptunes are partially gaseous worlds smaller than Neptune. Together, the two types of planet are the most common classes of world discovered by exoplanet hunters so far. (Planets smaller than Earth may indeed be more common, but they are harder to detect, so we haven't found as many.) What's curious is that our solar system contains neither a super-Earth nor a sub-Neptune, and astronomers don't know why our solar system lacks one of these common planets, or how such worlds form.

This is why the observations of V1298 Tau are such a big step forward. When a planet transits, or passes in front of, its host star, it blocks some of the star's light. The amount of light it blocks tells us the planet's radius. The frequency with which we see that planet transit then tells us its orbital period. The four planets have orbital periods of 8.2, 12.4, 24.1 and 48.7 Earth days, respectively. This is a very compact system — all four planets could easily fit inside the orbit of our solar system's innermost planet, Mercury.

Because the planets are all fairly close, their gravity tugs on each other, sometimes pulling a planet along its orbit a little faster, and sometimes causing it to go a little slower, depending on the respective planets' relative locations. This results in the planets sometimes being a little late or a little early for their scheduled transit. These transit timing variations, or TTVs, can tell researchers the mass of the planets: The greater the variation in the timing of a transit, the more massive the mass of the planet pulling on the transiting world.

With the radii and the masses of the planets known, Livingston's team could then calculate the densities of the planets, and found them to be extremely light.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"The unusually large radii of the young planets led to the hypothesis that they have very low densities, but this had never been measured," said Trevor David in a statement. "By weighing these planets for the first time, we have provided the first observational proof. They are indeed exceptionally puffy, which gives us a crucial, long-awaited benchmark for theories of planet evolution."

Indeed, the planets are some of the least dense known. They all formed with an extended atmosphere, like Neptune, but because they are so close to their star, extreme ultraviolet light and X-rays are heating their atmospheres. This causes the atmosphere of each world to expand and become bloated — so bloated, in fact, that the planets only have a loose grip on their atmosphere. Consequently, the atmosphere on each world is inevitably being stripped into space by the stellar wind of radiation. This process is known as photoevaporation. Livingston's team even looked for the spectral features of these outflows from the planets, but their signal is overpowered by the strong stellar winds.

The photoevaporation will continue for another 100 million years, by which time the planets will have been whittled down. The measurements suggest that all four worlds have a similar-size rocky core. The inner two worlds appear on course to lose their atmospheres altogether and become rocky super-Earths. The outer two planets are currently twice as massive, as their greater distance from their star offers them a little protection, but they too are on track to either lose their atmospheres entirely, or to keep some of it and evolve into mini-Neptunes.

The compact nature of their orbits suggests that this is how peas-in-a-pod systems, such as the worlds of TRAPPIST-1, form — planets of similar size and mass all on regularly spaced, circular orbits.

"What's so exciting is that we're seeing a preview of what will become a very normal planetary system," said Livingston. "The four planets we studied will likely contract into super-Earths and sub-Neptunes — the most common types of planets in our galaxy, but we've never had such a clear picture of them in their formative years."

The findings were reported on Jan. 7 in the journal Nature.

Keith Cooper is a freelance science journalist and editor in the United Kingdom, and has a degree in physics and astrophysics from the University of Manchester. He's the author of "The Contact Paradox: Challenging Our Assumptions in the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence" (Bloomsbury Sigma, 2020) and has written articles on astronomy, space, physics and astrobiology for a multitude of magazines and websites.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.