Astronomers discover the 'growing pains' of teenage exoplanets

"We've often seen the 'baby pictures' of planets forming, but until now, the 'teenage years' have been a missing link."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

When the Undertones sang about "Teenage Kicks," they could well have been inadvertently referring to the chaotic and violent "teenage" periods of planetary systems that are shaped by collisions between bodies of various sizes, such as the impact upon Earth by a massive body that created the moon.

Now, using the world's largest radio telescope project, the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA), astronomers have captured snapshots representing the chaotic "teenage years" of planets forming around infant stars.

The breakthrough, made as part of the Resolve exoKuiper belt Substructures (ARKS) survey being conducted by ALMA, could not only help scientists better understand the processes that drive the evolution of planetary systems, but it could also help us better understand a turbulent period of our own solar system's history that has, until now, been shrouded in mystery.

"We've often seen the 'baby pictures' of planets forming, but until now, the ‘teenage years’ have been a missing link," team co-leader Meredith Hughes of Wesleyan University, Connecticut, said in a statement. "This project gives us a new lens for interpreting the craters on the moon, the dynamics of the Kuiper Belt, and the growth of planets big and small. It’s like adding the missing pages to the Solar System's family album."

Teenage kicks

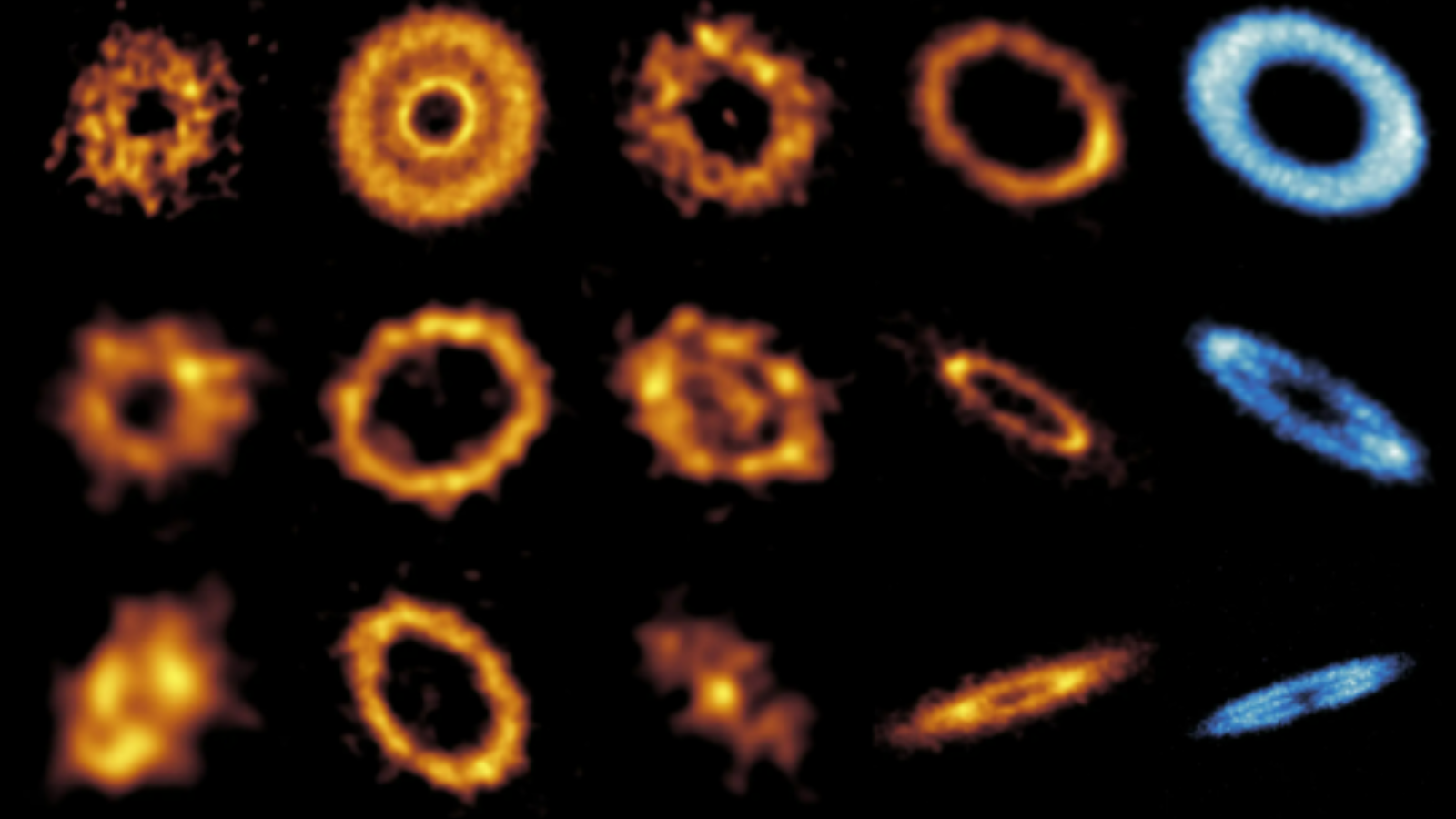

Hughes and colleagues used the 66 radio telescopes located in the Atacama desert region of northern Chile that make up ALMA to observe 24 disks of dusty debris around infant stars, the detritus that remains after planets have formed.

"Debris discs represent the collision-dominated phase of the planet formation process," ARKS team member Thomas Henning of the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy (MPIA) said. "With ALMA, we are able to characterise the disc structures pointing to the presence of planets. In parallel, with direct imaging and radial velocity studies, we are searching for young planets in these systems."

Evidence of this period of the solar system's history can be seen in the icy ring of comets beyond the orbit of Neptune known as the Kuiper Belt. These objects were created through massive collisions and planetary migrations that occurred around the sun billions of years ago, around the same time as Earth's moon was forming.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Planet baby pictures are fairly easy to obtain because the gas-rich disks in which they form, protoplanetary disks, are bright. Debris disks like the 24 seen by ALMA are thousands of times fainter, which is why they have proved so elusive for many years.

ALMA collected the radio wavelength emissions from dust particles and other molecules in these disks to build a picture of their complex structures, revealing multiple rings, wide and smooth outer halos, and unexpected arcs and clumps.

"We're seeing real diversity – not just simple rings, but multi-ringed belts, halos, and strong asymmetries, revealing a dynamic and violent chapter in planetary histories," ARKS team member and University of Exeter researcher Sebastián Marino said.

The key to this level of detail is the fact that with its 66 antennas, ALMA and its radio interferometry technique provide a wider view than any single telescope. This has confirmed that the teenage phase of planetary systems is a time of great upheaval.

"These discs record a period when planetary orbits were being scrambled and huge impacts, like the one that forged Earth's moon, were shaping young solar systems," team member Luca Matrà, of Trinity College Dublin, Ireland, added.

The team's research was published on Tuesday (Jan. 20) in the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics.

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. whose articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space, Newsweek and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University. Follow him on Twitter @sciencef1rst.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.