Scientists capture 51 images showing exoplanets coming together around other stars: 'This data set is an astronomical treasure'

The Very Large Telescope's SPHERE instrument captured unprecedented images of 51 dusty rings shaping young planetary systems.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Astronomers have unveiled a stunning new gallery of dusty rings encircling young stars, revealing the intricate architecture of developing planetary systems.

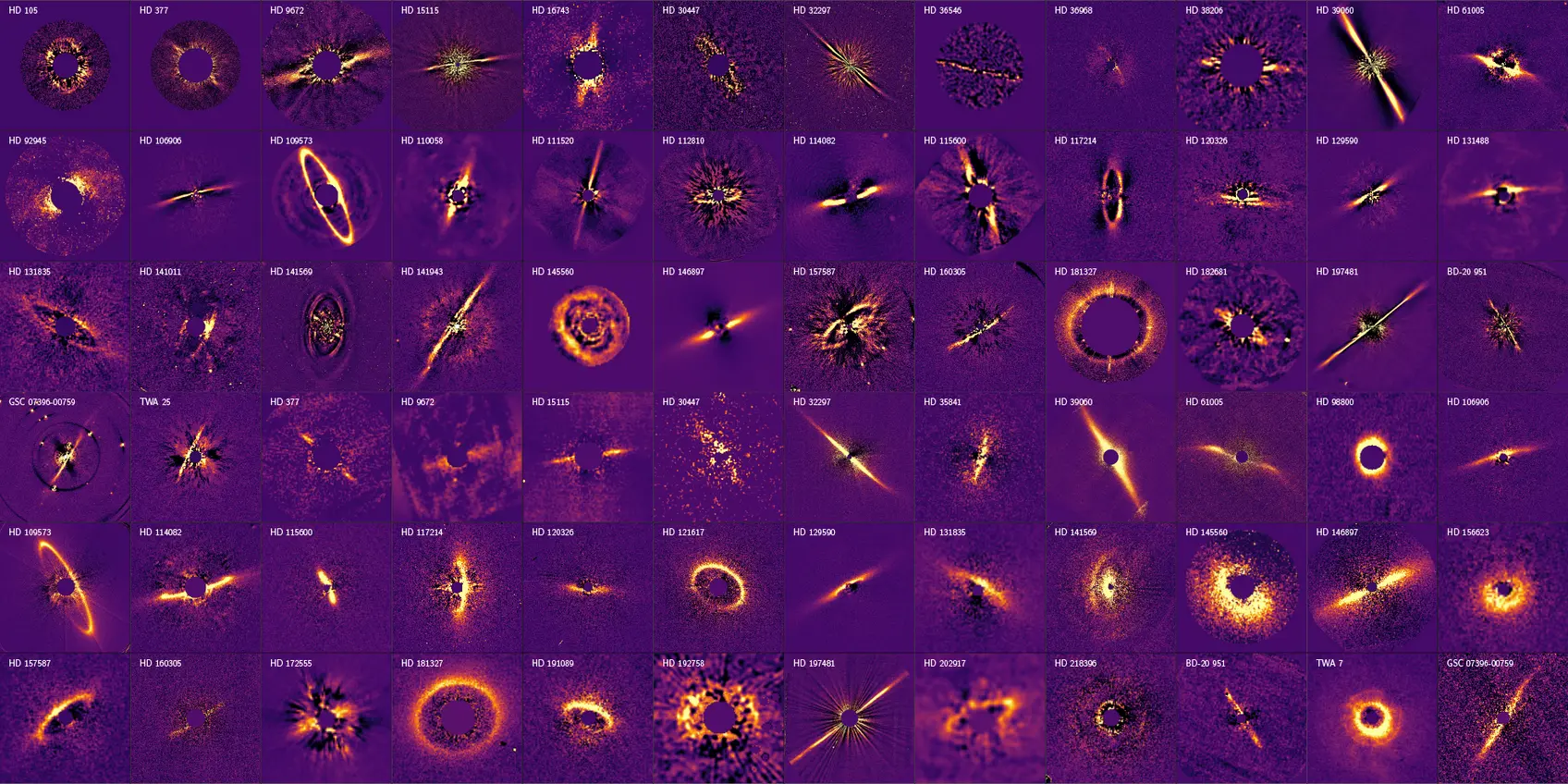

Using observations from the European Southern Observatory's (ESO) Very Large Telescope, astronomers documented 51 budding exoplanetary systems after studying 161 nearby stars, offering an unprecedented glimpse at debris disks around stars beyond our solar system. These debris disks are formed by collisions between asteroids or comets that generate large amounts of dust and resemble our own solar system where asteroids collect in the inner belt and comets populate the distant Kuiper Belt, according to a statement.

"This data set is an astronomical treasure," Gaël Chauvin, co-author of the study and SPHERE project scientist, said in the statement. "It provides exceptional insights into the properties of debris disks, and allows for deductions of smaller bodies like asteroids and comets in these systems, which are impossible to observe directly."

Scientists study debris disks because they offer a snapshot of what young solar systems look like after planets begin to form. Young stars form within collapsing clouds of gas and dust, which flatten into broad protoplanetary disks where material gradually clumps into larger bodies. As these systems mature, collisions between leftover asteroids and comets produce fine dust creating the debris disks we see today. By examining how this dust reflects starlight, astronomers can piece together how planets grow and how systems like our own take shape over time.

However, debris disks fade as collisions become less frequent and dust is gradually removed — either because it's blown out by stellar radiation, swept up by planets or remaining planetesimals or has fallen into the central star. Our solar system is an example of the end state of this process, with just the asteroid belt, the Kuiper Belt and faint zodiacal dust remaining.

Using advanced instruments like SPHERE allows astronomers to study the dust in younger systems — roughly the first 50 million years — that can still be detected. Most importantly, SPHERE blocks starlight using a coronagraph, a small disk that physically masks the star to reveal faint surrounding objects. The telescope's adaptive optics system corrects for atmospheric distortions in real time, and optional polarization filters enhance sensitivity to light reflected by dust, making debris disks easier to detect.

The new survey reveals remarkable variety, from narrow rings to wide diffuse belts, lopsided disks and disks viewed both edge-on and face-on. In fact, four of the disks were imaged in this detail for the first time, the researchers said.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Striking views of HD 197481 and HD 39060 capture sharp streams of material darting out from either side of its central star (representing an edge-on view), while incredible views of systems like HD 109573 and 181327 capture a nearly perfect circular debris ring (representing a face-on view).

In many systems, dust congregates in sharply defined rings, hinting at unseen planets shaping the debris, much like Neptune molds the Kuiper Belt in our solar system. On the other hand, the dust distribution in younger systems like HD 145560 and HD 156623 is more chaotic and billowy, where less defined structures suggest material hasn't yet been fully sculpted by planets or cleared by collisions.

Comparing the different structures within the disks revealed clear trends, like more massive stars tend to host more massive disks, and disks with material concentrated farther from the star also generally contain more mass, according to the statement.

"All of these belt structures appear to be associated with the presence of planets, specifically of giant planets, clearing their neighborhoods of smaller bodies," researchers said in the statement. "In some of the SPHERE images, features like sharp inner edges or disk asymmetries give tantalizing hints of as-yet unobserved planets."

While some giant exoplanets have already been detected in these systems, the SPHERE survey offers a guide post for new targets to be studied in greater detail by instruments like the James Webb Space Telescope and ESO's Extremely Large Telescope, which could reveal the exoplanets responsible for sculpting these spectacular disks.

Their findings were published Dec. 3 in the journal Astronomy and Astrophysics.

Samantha Mathewson joined Space.com as an intern in the summer of 2016. She received a B.A. in Journalism and Environmental Science at the University of New Haven, in Connecticut. Previously, her work has been published in Nature World News. When not writing or reading about science, Samantha enjoys traveling to new places and taking photos! You can follow her on Twitter @Sam_Ashley13.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.