I watched scientists track interstellar comet 3I/ATLAS leaving the solar system in real-time: 'This is some prime-time science'

"These images are not just pretty."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

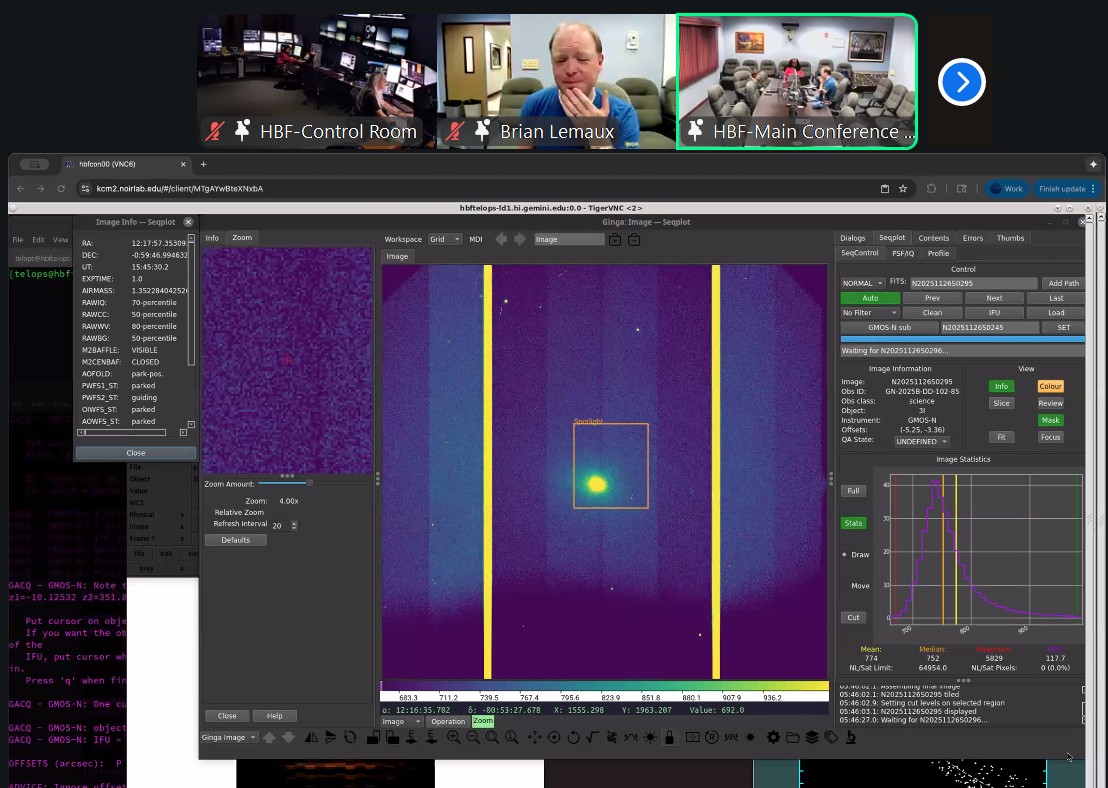

It was 4 a.m. on Nov. 25 at the top of Hawaii's dormant Maunakea volcano. The process to view the comet took less time than expected.

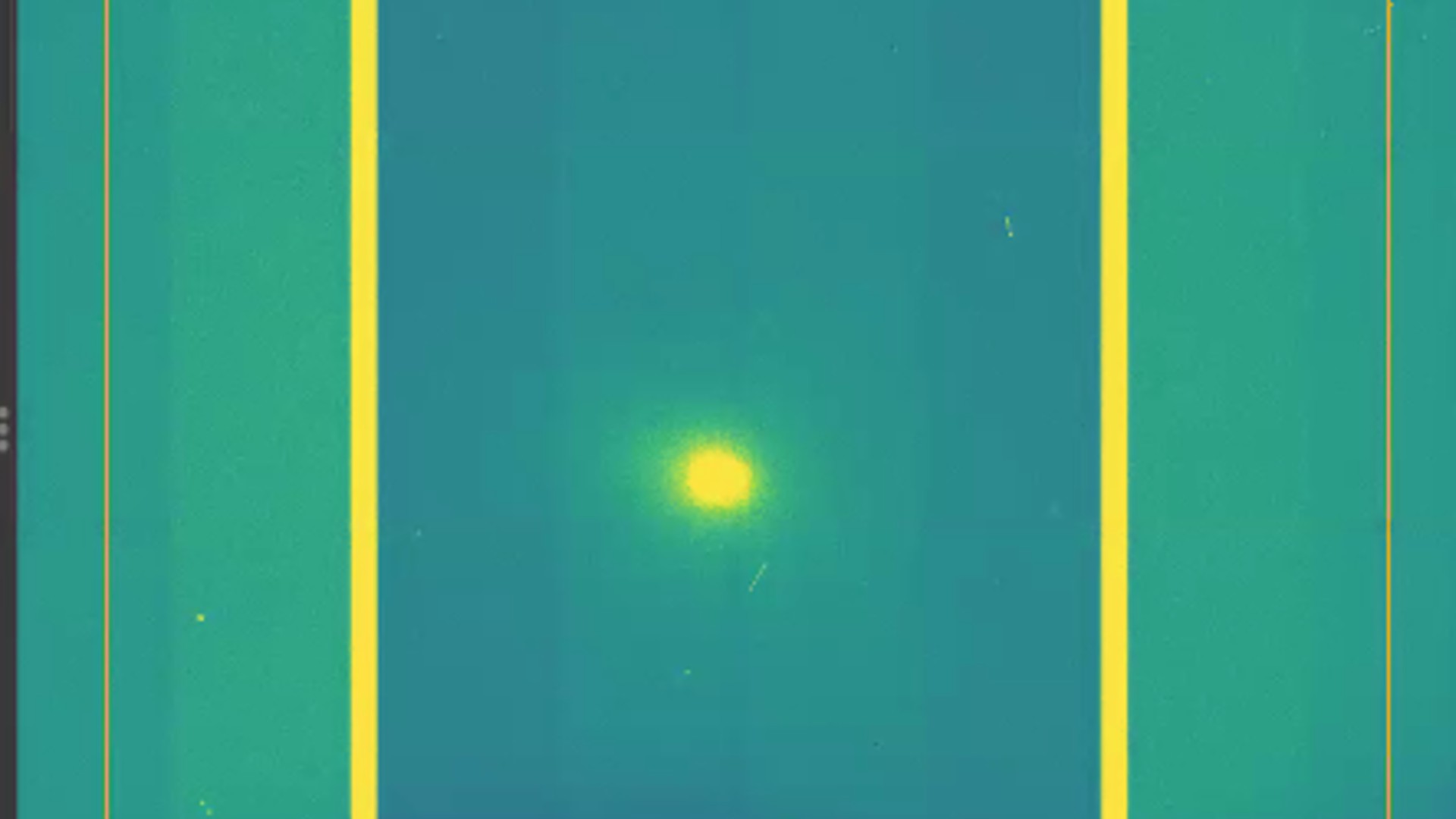

On the main screen, the subject at hand, interstellar comet 3I/ATLAS was a small, fuzzy blob drifting through a crowded field of stars. On another, its light had been stretched into a barcode of rainbow lines, some brighter than others, each corresponding to a different gas boiling off the object's nucleus.

"This is some prime-time science happening in real-time right now," said Bryce Bolin, principal investigator of a study on the interstellar comet, as he greeted a global audience logged into the online skywatching session. The session was hosted by Shadow the Scientists, an organization that directly connects experts and non-experts through virtual seminars like this recent one, and the Gemini North Telescope, one half of the international Gemini Observatory.

If you're hoping to see a comet through a telescope, you may want to consider this Celestron Astro Fi 130mm, which made our list for the top telescopes for viewing comets.

What we were really watching on the control room's screen, though, wasn't just a comet. It was a time capsule: a chunk of ice and rock that may be older than the sun, now on its out of our solar system after accidentally passing by on its cosmic voyage through the universe. It even managed to get a close pass by our star, the sparkling orb it has spent most of its existence watching from afar.

And this wasn't the International Gemini Observatory's first date with 3I/ATLAS.

Back in August, while the comet was still diving toward the sun, Chile's Gemini South telescope, the other half of the international observatory, captured pre-perihelion spectra and images as its tail "switched on" and began to grow. Those data showed a distinctly comet-like object with a bright coma and jets of gas dominated by carbon dioxide and cyanogen — a contrast to the water-rich behavior seen in most solar system comets.

By late October, 3I/ATLAS had whipped through perihelion, or its closest spot to our solar system's sun, at about 130,000 miles per hour (roughly 209,000 kilometers per hour), then disappeared behind the sun from Earth's point of view. This journey was captured by many telescopes and spacecraft, from the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter to even the Perseverance rover. Unfortunately, though, with the Gemini Observatory being on Earth, it didn't catch the show.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

But now, in November, I watched from my laptop as 3I/ATLAS climbed into northern skies as Hawaii's Gemini North Telescope took over.

"This is our first observation from Gemini since it reappeared behind the sun," explained scientist Brian Lemaux. "We're under active observations right now, which is what Shadow the Scientists is all about. this is not a show. We're actually trying to analyze and understand the data. The comet is very dynamic," he added. In other words, its brightness and spectral features had changed since the Gemini South run.

Before Gemini North ever pointed at 3I/ATLAS, we watched the calibration dance.

On screen, Lemaux showed a spectrum: bright, vertical lines corresponding to known elements used to nail down the wavelength scale to see the interstellar comet more accurately. "All these vertical lines are different chemical species of known origin that we can use to calibrate the observation," he said.

They followed that with flat fields — uniformly illuminated frames to correct for imperfections in the instrument — and a carefully chosen "solar analog" star. Because the comet mostly reflects sunlight, they needed to divide that sunlight out to isolate the comet's own emissions.

"The telescope optics are imperfect. The atmosphere is a problem from the ground. Our instruments, despite being very awesome, are not perfect either," Lemaux said. "We want to not care about any of that. We want to get to the intrinsic nature of any source that we observe."

Only once those pieces were in place did they move to the main act: a long-slit spectrum across the coma, followed by an integral field unit (IFU) observation — essentially a tiny 3D data cube giving a spectrum at every point in a small image of the comet.

Last time, at Gemini South, that combination of data delivered a surprise. "We saw this big plume of what turned out to be cyanogen gas," Bolin recalled, "and it extended out from the comet to very large scales."

Now, post-perihelion, the team was looking for how that structure had changed, how the aging of the coma after closest approach could show up in its chemistry and shape.

How old is 3I/ATLAS?

During a lull between exposures, someone in the webinar chat asked a deceptively simple question: How long does it take this comet to go around the galaxy?

"The galactic orbital period of 3I/ATLAS is about 250 million years," Bolin replied. (That's roughly the time it takes the sun to complete one lap around the Milky Way.) "It's probably not its first rodeo," he added. In extragalactic astronomy, he joked, 100 million years is considered "instantaneous" by experts.

That throwaway answer anchors a much deeper story about 3I/ATLAS's age.

Two groups of researchers tackled the problem by treating 3I/ATLAS the way we treat stars: comparing its velocity to the known relationship between age and random motion in the galaxy.

A study by scientists Aster Taylor of the University of Michigan and Darryl Seligman of Michigan State University calculated a "kinematic age" from 3I/ATLAS's excess speed of about 36 miles per second (58 kilometers per second) relative to the sun. Their result: the interstellar comet is likely 3 billion to 11 billion years old, assuming interstellar objects and stars follow the same age–velocity relation.

A different study by scientist Matthew Hopkins at the University of Oxford and colleagues, used a model that focused on the Milky Way's thick disk, a population of older, dynamically "hotter" stars, to infer a likely age of the interstellar comet at between about 7.6 billion and 14 billion years.

Both lines of evidence point the same way: 3I/ATLAS is almost certainly older than our 4.6-billion-year-old sun, and may be among the oldest comets we've ever seen.

In our seminar, Bolin later showed a visualization of 3I/ATLAS's orbit around the galaxy — no neat ellipse, but rather a looping, spiraling path distorted by encounters with gas clouds, spiral arms and dark matter.

"These aren't simple ellipses anymore," he said.

An asteroid around the sun has a closed elliptical orbit; an interstellar comet in the Milky Way doesn't. The galaxy's "very inhomogeneous clumps of matter," as Bolin described, constantly tug on the interstellar comet, making it nearly impossible to back-trace 3I/ATLAS to a specific parent star.

In other words, 3I/ATLAS has been wandering so long that it has lost its return address.

Imaging this ancient comet

As the Hawaiian sky crept toward dawn, the spectral work wound down. The Gemini North team cycled through four filters to look at the interstellar comet.

The comet brightened and faded slightly from image to image as different parts of its spectrum came into view.

"These images are not just pretty," Bolin emphasized. They're being used to pin down 3I/ATLAS's exact position on the sky with exquisite precision.

When the last images came in, Shadow the Scientists staffer Jameeka Marshall reminded the audience that all the data would be public immediately: "There's zero 'proprietary time' associated with the data … anybody that's interested can take these data, reduce the data and make them in a scientifically viable form using the tools that we have here at the Gemini Observatory."

Outside the control room, sunrise threatened the image quality. Inside, the comet on the screen looked unchanged: a fuzzy blot of light with a tail barely hinted at against the brightening sky.

Hidden in those frames and spectra is the biography of a traveler that has been aging in interstellar space since long before Earth formed; a relic from an early, metal-poor corner of the galaxy, briefly caught in our telescopes on its way past.

For a few hours on Maunakea — and for a few months in 2025 through 2026 as observatories worldwide tracked it — comet 3I/ATLAS has given us something astonishingly rare: a direct look at the debris of someone (or something) else's planetary system, eroded by billions of years.

But not erased.

Kenna Hughes-Castleberry is the Content Manager at Space.com. Formerly, she was the Science Communicator at JILA, a physics research institute. Kenna is also a freelance science journalist. Her beats include quantum technology, AI, animal intelligence, corvids, and cephalopods.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.