Could the remains of a 'dead' comet still be in the solar system? Astronomers are still searching 6 years later

"How many presumably disrupted comets have really completely disrupted, and could any of them have actually survived with a reduced, inactive nucleus?"

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

The fate of a comet that was predicted to pass close to Earth remains a mystery five years after its dramatic breakup in the inner solar system — but some astronomers think a part of it might still be out there.

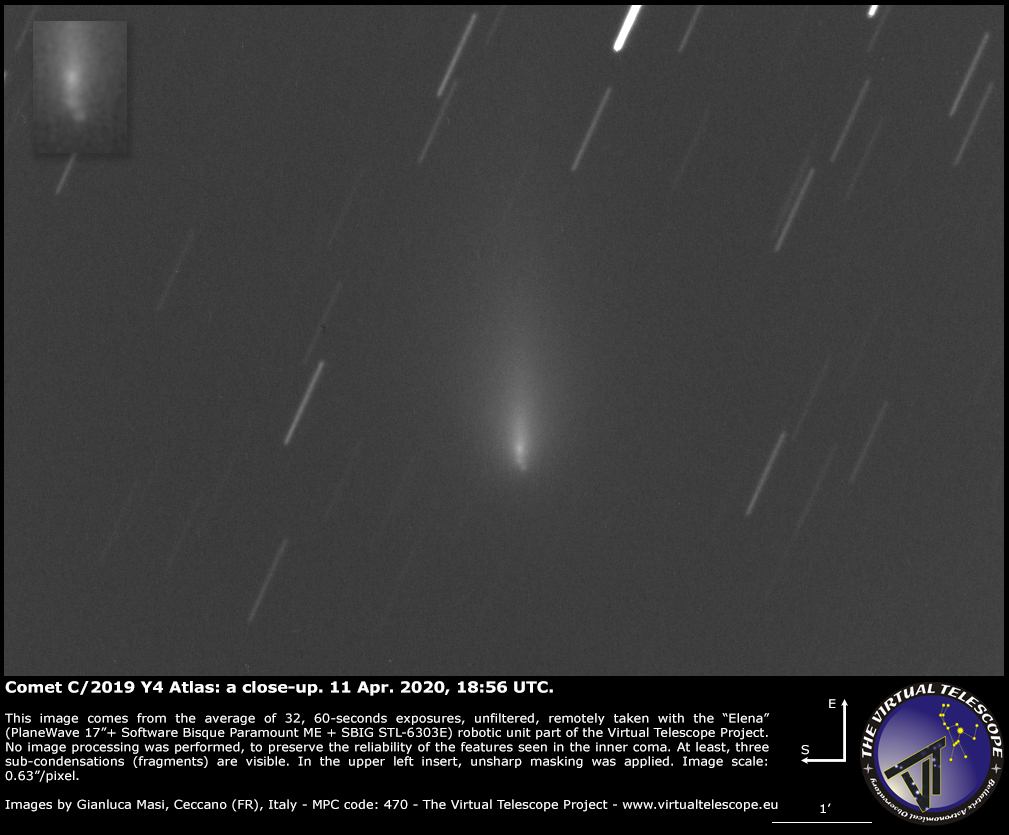

In early 2020, astronomers discovered the icy traveler, known as C/2019 Y4 ATLAS, and predicted it might provide a night-sky spectacle that would liven up everyone's COVID-19 pandemic lockdown: a comet visible with the unaided eye as it passed within 23 million miles (37.5 million kilometers) of the sun, or about one quarter of the distance at which Earth orbits our star. But then the comet broke into dozens of pieces, leaving would-be observers hanging — and leaving astronomers wondering whether there could still be anything substantial left of our ill-fated icy visitor.

A team of astronomers led by Salvatore A. Cordova Quijano of Boston University hoped to answer that question by scanning the autumn 2020 skies. And according to their recent paper in The Astronomical Journal, there may be a half-kilometer-wide chunk of the comet still in orbit, swinging back outward toward the cold darkness of the outer solar system.

The lost comet's remains could still be out there

Cordova Quijano and co-authors Quanzhi Ye and Michael S. P. Kelley scanned the skies in August and October of 2020, searching for any sign of the comet's remnants, to no avail. Observations with the Lowell Discovery Telescope (a 4.3-meter telescope in Arizona) and nightly images from the Zwicky Transient Facility (which makes a wide-view scan of the northern sky every two nights, looking for changing or short-lived objects like comets and supernovas) turned up nothing. But that doesn't mean there's nothing left of C/2019 Y4; it might just mean that what's left is smaller than the smallest fragment these telescopes would have been able to see, which comes out to about half a kilometer wide.

Besides solving an intriguing astronomical mystery, this new study of C/2019 Y4 offers some clues about what happens when comets break apart in the intense heat near the sun, as well as a chance to study the millennia-long decline of an ancient comet family (C/2019 Y4 might be a fragment of a larger comet which broke up thousands of years ago, according to a 2021 study).

"The uncertain fate of C/2019 Y4 raises an intriguing question," the astronomers wrote in the study. "How many presumably disrupted comets have really completely disrupted, and could any of them have actually survived with a reduced, inactive nucleus?"

In the case of C/2019 Y4, the answer to that second question may be yes: it's possible that a fragment of comet, less than half a kilometer wide, could still be tracing its larger parent's long path around the sun.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

A dramatic backstory

Comet C/2019 Y4 ATLAS was just a faint smudge of light in the distance when astronomers with the Asteroid Terrestrial-impact Last Alert System first spotted it in December 2019. The comet started getting brighter very quickly in early 2020 as it flew toward the inner solar system, and astronomers excitedly predicted that it could be visible with the unaided eye by the time it made its closest pass to Earth in late May.

And then, like the rest of us, C/2019 Y4 suddenly fell apart in late April 2020.

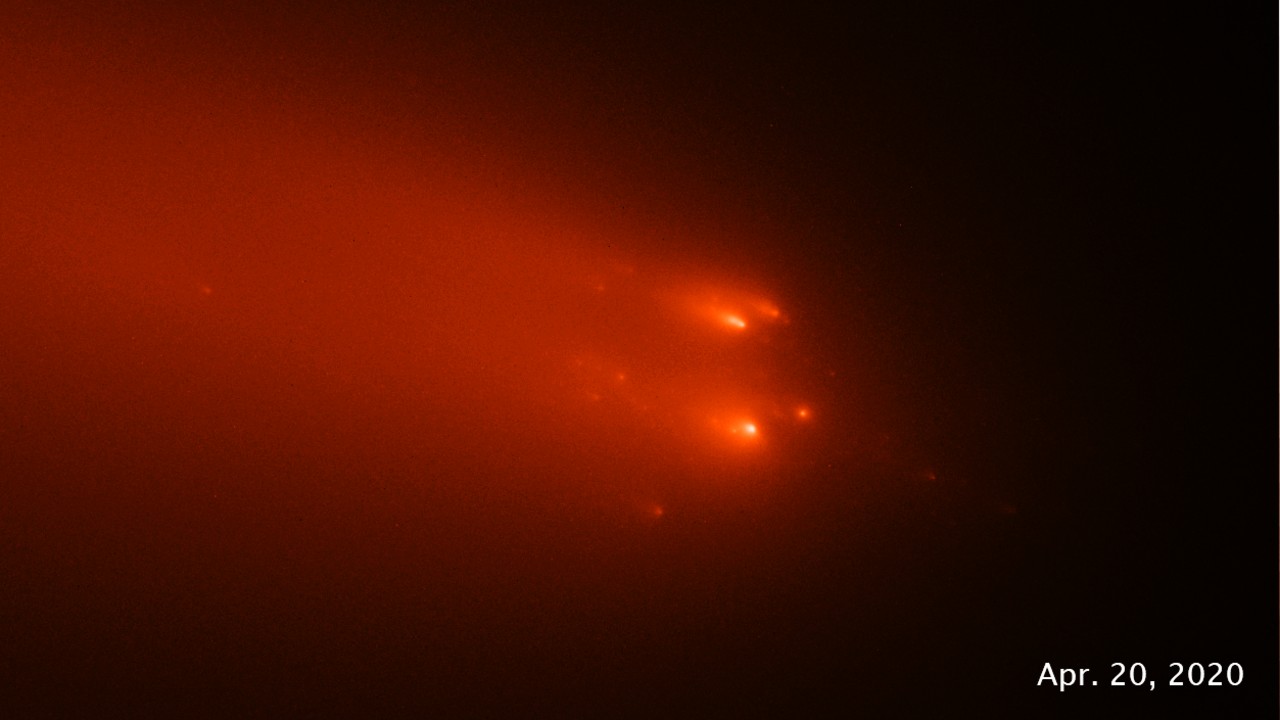

In the aftermath, astronomers used the Hubble Space Telescope and other observatories around the world to track a couple of dozen pieces of the shattered comet, in what appeared to be grouped in four main clusters of icy debris. But one of those clusters later turned out to be a glitch in the data, and another only lasted for a few days before completely dissipating. That left two more debris clusters, dubbed fragment A and fragment B.

Astronomers' last glimpse of any piece of C/2019 Y4's icy debris was on June 8, 2020, in images from NASA's STEREO spacecraft, nine days after the comet's closest approach to the sun. At the time, the comet's nucleus definitely looked "completely disrupted," Cordova Quijano and colleagues wrote. The lingering question is what happened to the nucleus after those observations.

By now, Fragment A is probably nothing but a slowly-spreading cloud of gas and maybe some dust grains. Within the first three days after the breakup, the chunks of former comet nucleus that made up fragment A seemed to lose about 70% of their mass (because, again, ice sublimates, and smaller chunks tend to sublimate faster than big ones).

Just before perihelion, in late May 2020, the biggest chunk of fragment B was about 0.75 miles, or 1.2 kilometers wide. By the time of Cordova Quijano and colleagues' observations in late August and mid-October 2020, it was clear that "fragment B had undergone further major disintegration," but it's still not clear exactly how much. Cordova Quijano and co-authors couldn't spot any trace of fragment B in their Lowell or Zwicky data, which could mean there's nothing left — or that the remaining fragment is less than half a kilometer wide.

"We cannot conclude from the available data whether any sizable fragments still exist," they wrote. "Observed disintegration events have produced long-lasting fragments as small as 0.3 kilometers diameter, which is smaller than our detection limit."

How to catch the next one

For astronomers, C/2019 Y4's dramatic breakup offered a rare chance to watch a comet disintegrate. So far, they've only gotten to observe this dramatic phenomenon a handful of times: three confirmed and four only suspected. Of those four, astronomers have no real idea what happened after the breakup — like whether any large chunks survived long enough to make it out of the hot inner solar system — and according to Cordova Quijano and his colleagues, that's mostly because of a lack of follow-up observations to confirm the comets' fates.

The researchers wrote that about two or three months after each comet passed "behind" the sun from our viewpoint, then emerged again, it should have been easier for telescopes to see. This would have been a perfect time to look for surviving fragments — or their absence. Such observations would have confirmed the comets' demise and also shed light on whether smaller pieces of their shattered nuclei would keep orbiting the sun as mini-comets.

"For C/2019 Y4, a deep search right after the solar conjunction (such as immediately following the initial shallower search in early August of 2020) could have conclusively determined the state of the remnant," they wrote in their recent paper. "Similarly, dedicated deep searches would be helpful in closing cases like the other three comets and would provide insights into comet disruption dynamics."

It's a little too late to do that for C/20129 Y4, but the study offers a heads-up to astronomers to be prepared for these kinds of observations the next time a comet falls apart on its way through the inner solar system.

Kiona Smith is a science writer based in the Midwest, where they write about space and archaeology. They've written for Inverse, Ars Technica, Forbes and authored the book, Peeing and Pooping in Space: A 100% Factual Illustrated History. They attended Texas A&M University and have a degree in anthropology.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.