James Webb Space Telescope discovers young galaxies age rapidly: 'It's like seeing 2-year-old children act like teenagers'

"The knowledge of these will ultimately help us understand the formation of the first stars and planets and how our own Milky Way came into being."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

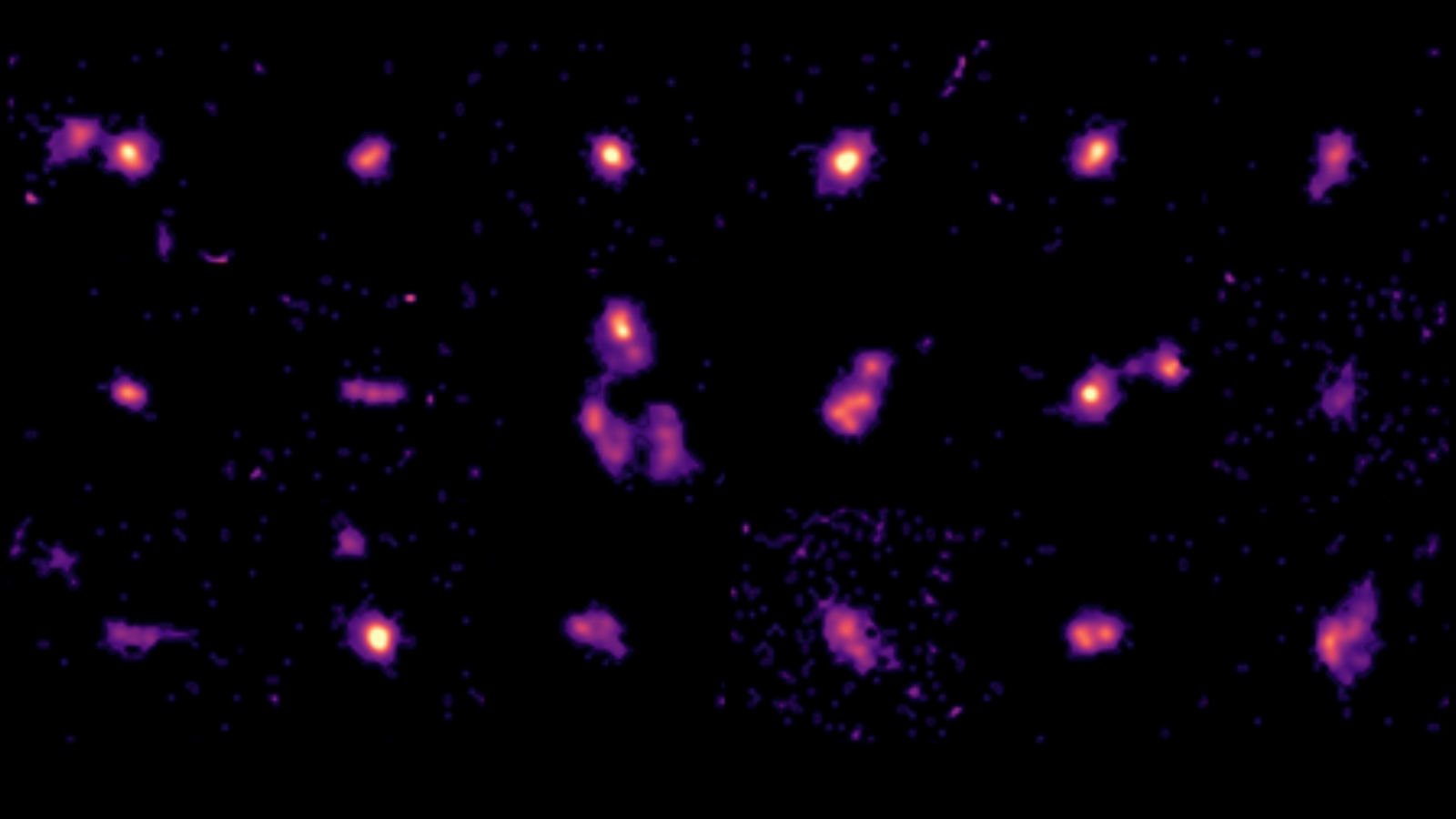

Astronomers have obtained their most detailed look yet at young galaxies in the early universe using the James Webb Space Telescope, Hubble Space Telescope and Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array. The conclusion? These cosmic adolescents grew up incredibly fast.

The team behind this research observed 18 galaxies located around 12.5 billion light-years away over a range of wavelengths of light. Existing just over 1 billion years after the Big Bang, these galaxies were in the midst of rapid star formation and were therefore undergoing explosive growth.

The team's most important discovery was the fact that these galaxies seem to have matured faster than previously expected in more than one way — but most strikingly, the galaxies are richer in elements heavier than hydrogen and helium, or "metals," as astronomers call them, particularly carbon and oxygen.

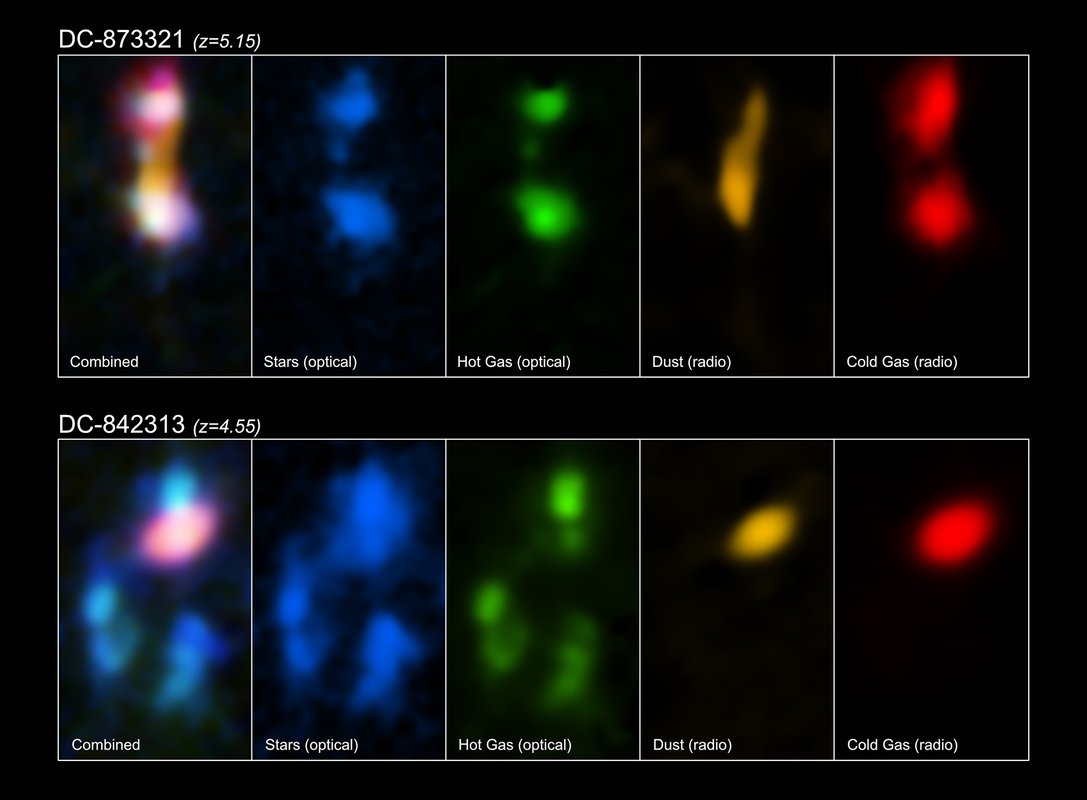

"With this sample, we are uniquely poised to study galaxy evolution during a key epoch in the universe that has been hard to image until now," team member Andreas Faisst of the California Institute of Technology (Caltech) said in a statement. "Thanks to these exceptional telescopes, we have spatially resolved these galaxies and can observe the stages of star formation as they were happening and their chemical properties when our universe was less than a billion years old."

Galaxies grow up too fast

When the first galaxies in the universe formed, the cosmos was filled with hydrogen and helium and just a smattering of heavier elements. The first stars and their home galaxies were correspondingly metal-poor. These stars forged metals during their lives and then dispersed them throughout their galactic homes in supernova explosions that marked their deaths. These heavy elements became the building blocks of the next generation of stars, which were more metal-rich than their predecessors.

However, this process of enrichment should take longer than 1 billion years, meaning the prematurely mature state of these early galaxies is curious, to say the least.

"It was a surprise to see such chemically mature galaxies," Faisst added. "It's like seeing 2-year-old children act like teenagers. How do metals form in less than 1 billion years?"

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Anyone living with human teenagers will tell you they have quite the appetites, and that is also true of these premature cosmic teens. The team found that the supermassive black holes in these galaxies are rapidly feeding, or accreting, surrounding matter. That means these black holes are also growing rapidly.

In addition to their anachronistically metal-rich nature, Faisst and colleagues discovered that many of the galaxies they studied had rotating stellar disks, similar to the spiral arms of our much more mature galaxy, the Milky Way. These features had also developed much earlier than previous models had predicted.

"Now, with this new survey, we can show that some of these galaxies were both structurally and chemically evolved," Faisst said.

It wasn't just the galaxies studied by these scientists that were unexpectedly metal-rich. The surrounding gas, the circumgalactic medium, was also similarly enriched.

"The galaxies show very flat gradients in their metal abundances, reaching out to more than 30,000 light-years," team member Wuji Wang of Caltech's Infrared Processing & Analysis Center said in the statement.

The team now intends to match their observations of these galaxies using simulations of galactic growth and metal enrichment.

"The combination of observations and simulations provides a powerful synergy to understand the details of star formation, and dust and metal production mechanisms," Faisst said. "The knowledge of these will ultimately help us understand the formation of the first stars and planets and how our own Milky Way came into being."

The team's research was presented at the 247th meeting of the American Astronomical Society in Phoenix on Tuesday (Jan.6), and was published in The Astrophysical Journal Supplement.

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. whose articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space, Newsweek and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University. Follow him on Twitter @sciencef1rst.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.