Scientists just made the 1st antimatter 'qubit.' Here's why it could be a big deal

Although the antimatter qubit won't find use in quantum computing, it will be used to test the differences between matter and antimatter.

Physicists at CERN — home of the Large Hadron Collider — have for the first time made a qubit from antimatter, holding an antiproton in a state of quantum superposition for almost a minute.

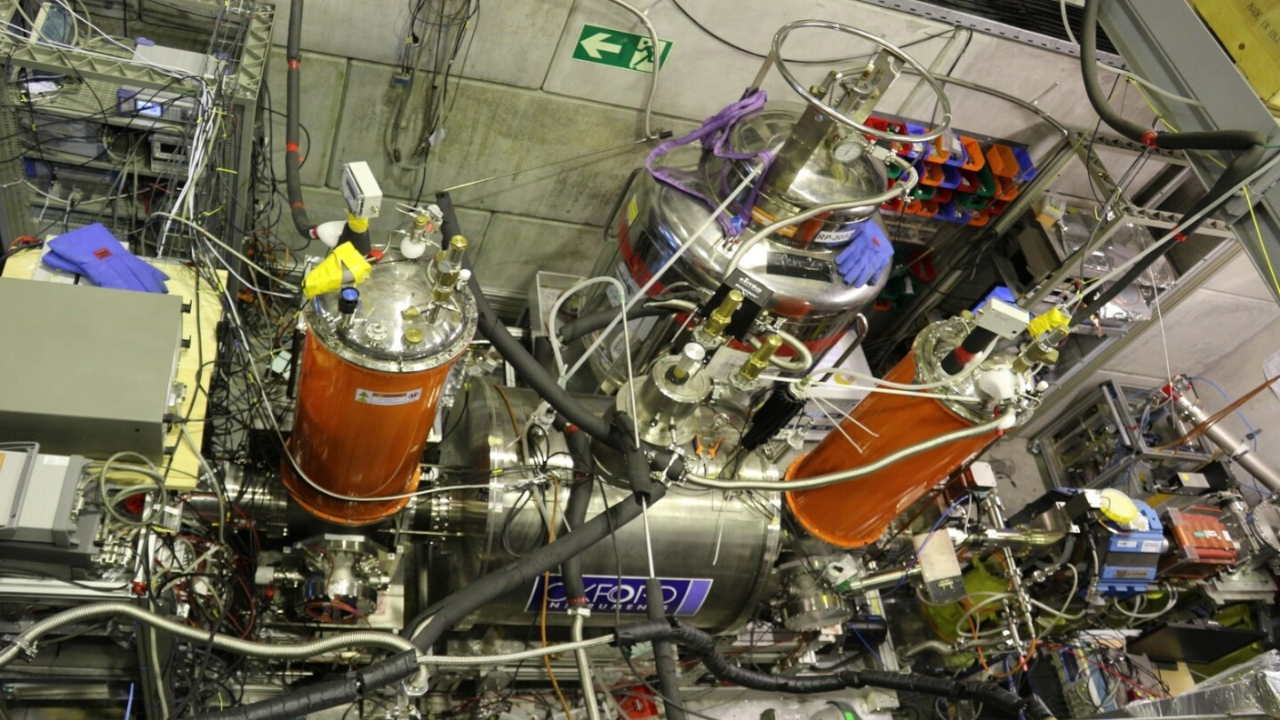

This landmark achievement has been performed by scientists working as part of the BASE collaboration at CERN. BASE is the Baryon Antibaryon Symmetry Experiment, which is designed to measure the magnetic moment of antiprotons – in essence, how strongly they interact with magnetic fields.

However, while qubits are commonly associated with quantum computing, in this case the antiproton qubit will be used to test for differences between ordinary matter and antimatter. It will specifically help probe the question of why we live in a universe so dominated by ordinary matter when matter and antimatter should have been created in equal quantities during the Big Bang.

They're opposites of one another, right?

A proton and antiproton have the same mass but opposite charges, for example. In physics, the mirror-image properties between matter and antimatter is referred to as charge-parity-time (CPT) symmetry. CPT symmetry also says that a particle and its antiparticle should experience the laws of physics in the same way, meaning that they should feel gravity or electromagnetism with the same strength, for example (that first one has actually been tested, and indeed an antiprotons falls at the same rate as a proton).

So, theoretically, when the universe came into existence, there should have been a 50-50 chance of antimatter or regular matter particles being created. But for some reason, that didn't happen. It's very weird. Even the BASE project found that, to a precision of parts per billion, protons and antiprotons do have the same magnetic moment. Alas, more symmetry.

However, the BASE apparatus has enabled physicists to take things one step further.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Antiproton antics

When matter and antimatter come into contact, they annihilate one another in a burst of gamma-ray photons, so BASE has to keep them apart. To do so, it uses something called Penning traps, which can hold charged particles in position thanks to the careful deployment of electric and magnetic fields. BASE has two primary Penning traps. One is called the analysis trap, which measures the precession of the magnetic moment around a magnetic field, and the other is the precision trap, which is able to flip the quantum spin of a particle and measure that particle's oscillation in a magnetic field.

Quantum physics tells us that particles are born in a state of superposition. Take, for instance, the property of quantum spin, which is just one example of the weirdness of the quantum universe. Despite the name, spin does not describe the actual rotation of a particle; rather, it describes a property that mimics the rotation. How do we know that it isn't a real rotation? If it were, then the properties of quantum spin would mean particles would be spinning many times faster than the speed of light — which is impossible.

So, fundamental particles like electrons, protons and antiprotons have quantum spin values, even if they are not really spinning, and these values can be expressed either as a whole number or a fraction. The quantum spin of a proton and antiproton can be 1/2 or –1/2, and it is the quantum spin that generates the particle's magnetic moment.

Because of the magic of quantum superposition, which describes how all the possible quantum states exist synchronously in a particle's quantum wave-function, a proton or antiproton can have a spin of both 1/2 or –1/2 at the same time. That is, at least until they are measured and the quantum wave-function that describes the quantum state of the particle collapses onto one value. That's another bit of weirdness of the quantum world — particles have all possible properties at once until they are observed, like Schrödinger's cat being alive and dead at the same time in a box, until someone opens the box. In fact, any kind of interaction with the outside world causes the wave function to collapse in a process known as decoherence.

Why this happens is a subject of great debate between the various interpretations of quantum physics.

Regardless, by giving an antiproton that is held firmly in the precision trap just the right amount of energy, BASE scientists have been able to hold an antiproton in a state of superposition without decohering for about 50 seconds — a record for antimatter (this has previously been achieved with ordinary matter particles for much longer durations). In doing so, they formed a qubit out of the antiproton.

Keep the qubits away!

A qubit is a quantum version of a byte used in computer processing. A typical, binary byte can have a value of either 1 or 0. A qubit can be both 1 and 0 at the same time (or, have a spin of 1/2 and –1/2 at the same time), and a quantum computer using qubits could therefore, in principle, vastly accelerate information processing times.

However, the antiproton qubit is unlikely to find work in quantum computing because ordinary matter can be used for that more easily without the risk of the antimatter annihilating. Instead, the antiproton qubit could be used to further test for differences between matter and antimatter, and whether CPT symmetry is violated at any stage.

"This represents the first antimatter qubit and opens up the prospect of applying the entire set of coherent spectroscopy methods to single matter and antimatter systems in precision experiments," said BASE spokesperson Stefan Ulmer, of the RIKEN Advanced Science Institute in Japan, in a statement. "Most importantly, it will help BASE to perform antiproton moment measurements in future experiments with 10- to 100-fold improved precision."

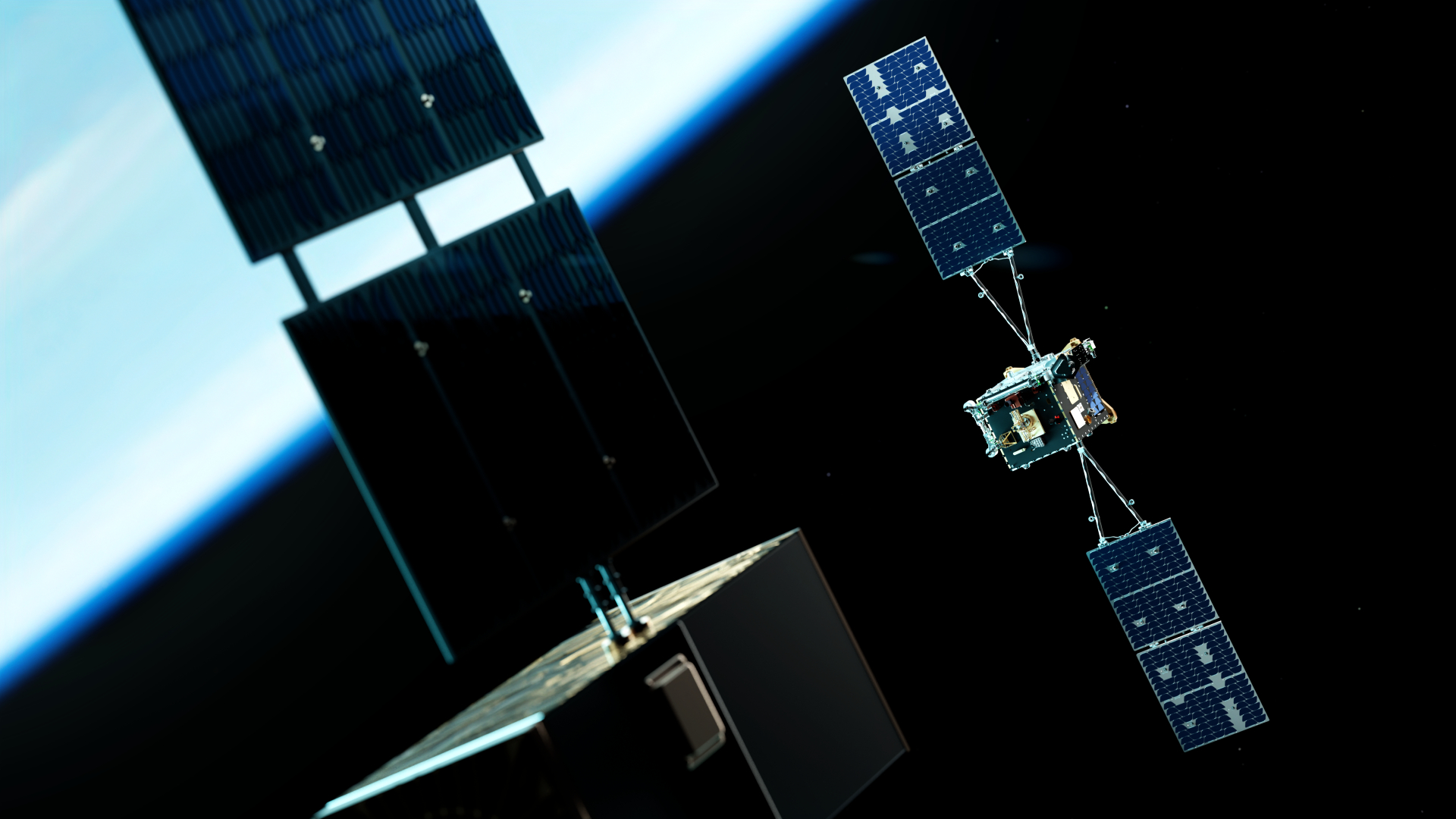

Currently, BASE's experiments have to take place at CERN, where the antimatter is created in the Large Hadron Collider. However, the next phase of antimatter research will be BASE-STEP (Symmetry Tests in Experiments with Portable Antiprotons), which is a device that contains a portable Penning trap, allowing researchers to move antiprotons securely away from CERN to laboratories with quieter, purpose-built facilities that can reduce exterior magnetic field fluctuations that might interfere with magnetic moment experiments.

"Once it is fully operational, our new offline precision Penning trap system, which will be supplied with antiprotons transported by BASE-STEP, could allow us to achieve spin coherence times maybe even ten times longer than in current experiments, which will be a game-changer for baryonic antimatter research," said RIKEN's Barbara Latacz, who is the lead author of the new study.

The results are described in a paper that was published on July 23 in the journal Nature.

Keith Cooper is a freelance science journalist and editor in the United Kingdom, and has a degree in physics and astrophysics from the University of Manchester. He's the author of "The Contact Paradox: Challenging Our Assumptions in the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence" (Bloomsbury Sigma, 2020) and has written articles on astronomy, space, physics and astrobiology for a multitude of magazines and websites.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.