Mysterious radio pulses detected high above Antarctica may be evidence of an exotic new particle, scientists say

"We still don't have an explanation for what those anomalies are."

A cosmic particle detector has spotted a burst of strange radio signals from the ice of Antarctica that currently defy explanation. The results could hint at the existence of new particles, or interactions between particles currently unknown to physics, scientists say.

The mystery radio pulses were picked up about 25 miles (40 kilometers) above Earth by the Antarctic Impulsive Transient Antenna (ANITA) experiment. ANITA is a series of instruments that float over Antarctica, carried by balloons with the aim of detecting ultra-high-energy (UHE) cosmic neutrinos and other cosmic rays as they pelt Earth from space.

ANITA usually picks up signals when they are reflected off the ice of Antarctica, but these pulses were different, coming from below the horizon at an orientation that currently can't be explained by particle physics.

"It's an interesting problem, because we still don't actually have an explanation for what those anomalies are," ANITA team member and Penn State University researcher Stephanie Wissel said in a statement. "What we do know is that they're most likely not representing neutrinos."

The radio waves detected by ANITA were oriented at very steep angles, 30 degrees below the surface of the ice.

This means that the signal had to pass through thousands of miles of rock before reaching ANITA. This should have led to interactions that left the radio pulses too faint to be detectable, but clearly that didn't happen here.

ANITA gets a hint of a new cosmic ghost

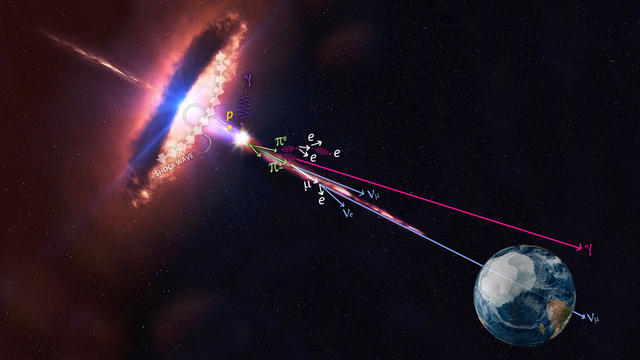

The immediately obvious suspect for this signal is neutrinos. After all, it is the signature of these particles that ANITA is designed to pick up. Neutrinos are unofficially known as "ghost particles" due to the fact that they carry no charge and are virtually massless.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Thus, as neutrinos — also the most abundant particles in the universe — stream through the cosmos at near-light speeds after being launched by powerful cosmic events, they can "phase" through matter, barely interacting.

That means they remain unchanged after traversing many light-years, making them incredible "messengers" that can teach scientists about the events that launched them. However, this ghostly nature also makes neutrinos incredibly tough to detect.

"You have a billion neutrinos passing through your thumbnail at any moment, but neutrinos don't really interact," Wissel said. "So, this is the double-edged sword problem. If we detect them, it means they have traveled all this way without interacting with anything else. We could be detecting a neutrino coming from the edge of the observable universe."

Fortunately, even catching one neutrino as it passes through Earth can reveal a wealth of information.

So, designing sophisticated experiments and taking them to remote regions of Earth or placing them deep underground in the hope of busting a cosmic ghost is well worth the effort for scientists like Wissel.

"We use radio detectors to try to build really, really large neutrino telescopes so that we can go after a pretty low expected event rate," Wissel said.

Just such an instrument, ANITA floats 25 miles over the ice of Antarctica, away from the possibility of other interfering signals, hunting for so-called "ice showers."

"We point our antennas down at the ice and look for neutrinos that interact in the ice, producing radio emissions that we can then sense on our detectors," Wissel continued.

These ice showers are caused by a particular "flavor" of neutrino called tau neutrinos, which strike the ice and interact to create a daughter particle called a tau lepton. This rapidly decays into an "air shower" containing even smaller constituent particles.

Distinguishing between air showers and ice showers reveals the characteristics of the initial interacting particle and the origin of this particle. Wissel compares the strategy to using the angle of a bounced ball to trace it back to its initial path.

However, because the angle of these newly detected signals is sharper than current models of physics allow, the backtracking process isn't possible in this case.

Even more confusingly, other neutrino detectors like the IceCube Experiment and the Pierre Auger Observatory didn't detect anything that could explain these signals and the upward-oriented air shower.

Thus, the ANITA researchers have declared the signals as "anomalous," determining they weren't the result of neutrinos. The signals could therefore be indicative of something new, perhaps even a hint of dark matter, the mysterious cosmic "stuff" that accounts for around 85% of the universe's matter content.

Further answers may have to wait for the "next big thing" in neutrino detection, the larger and more sensitive Payload for Ultrahigh Energy Observations (PUEO) instrument, currently being developed by Penn State.

"My guess is that some interesting radio propagation effect occurs near ice and also near the horizon that I don't fully understand, but we certainly explored several of those, and we haven't been able to find any of those yet either,” Wissel said. "So, right now, it's one of these long-standing mysteries, and I'm excited that when we fly PUEO, we'll have better sensitivity.

"In principle, we should pick up more anomalies, and maybe we'll actually understand what they are. We also might detect neutrinos, which would in some ways be a lot more exciting."

The team's research was published online in March in the journal Physical Review Letters.

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. whose articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space, Newsweek and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University. Follow him on Twitter @sciencef1rst.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.