Bleached Martian rocks offer fresh evidence of a wetter and warmer Mars: 'But where did they come from?

"You need so much water that we think these could be evidence of an ancient warmer and wetter climate where there was rain falling for millions of years."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

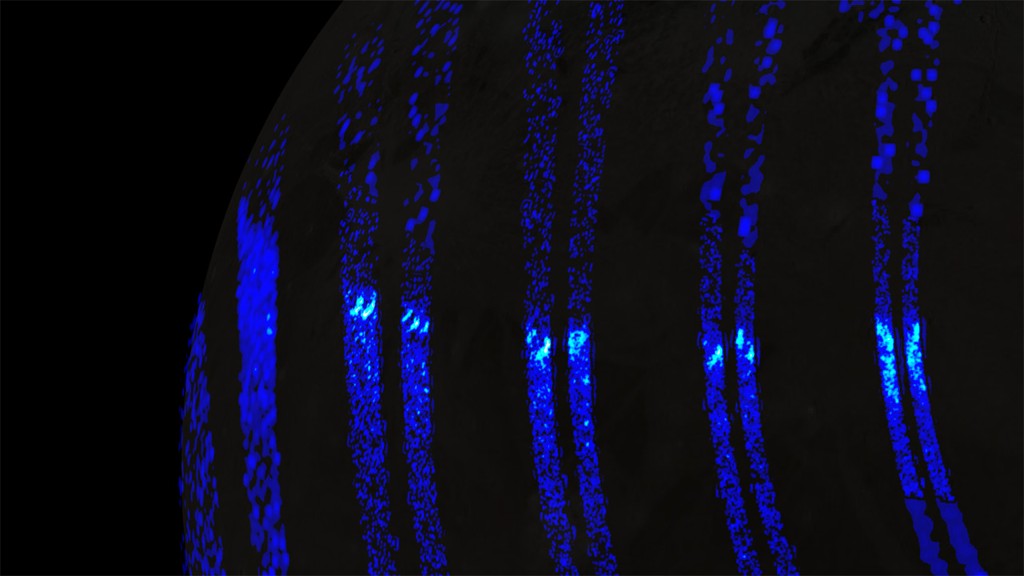

NASA's Perseverance rover has discovered thousands of strangely bleached rocks on Mars that are rich in a mineral difficult to form without long-term exposure to water, adding fresh evidence that the Red Planet was warmer, wetter and possibly rain-soaked billions of years ago.

The newfound Mars rocks are rich in kaolinite, a soft, white, clay mineral that, on Earth, typically forms when water slowly leaches other elements from rock over thousands to millions of years, a new study reports. On Earth, it is most commonly found in warm, humid environments such as rainforests, where frequent rainfall drives intense chemical weathering.

"All life uses water," Adrian Broz, a postdoctoral researcher at Purdue University who led the new study, said in a statement. "So when we think about the possibility of these rocks on Mars representing a rainfall-driven environment, that is a really incredible, habitable place where life could have thrived if it were ever on Mars."

"You need so much water that we think these could be evidence of an ancient warmer and wetter climate where there was rain falling for millions of years," added study co-author Briony Horgan, who is a professor of planetary science in the Department of Earth, Atmospheric and Planetary Sciences at Purdue University and a long-term planner on the Perseverance mission.

Perseverance identified several thousand of these kaolinite-rich rocks — ranging from small pebbles to large boulders — scattered across the surface of Jezero crater, the dry, bowl-shaped depression just north of Mars' equator that likely held a lake billions of years ago.

Since landing on Mars in 2021, the car-sized robot has explored the crater floor searching for evidence of past microbial life. Late last year, it climbed up the crater's inner wall and onto the rim, exploring new terrain. Scientists are trying to understand how that wetter era ended, when Mars lost its global magnetic field and particles from the sun began stripping away its thick atmosphere, transforming the planet into the cold, barren world seen today.

While kaolinite-bearing terrains on Mars had previously been identified from orbit, Perseverance's discoveries allow scientists to study such materials directly on the planet's surface, the study notes.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

To better understand how the Martian rocks formed, Broz and his team compared Perseverance data with kaolinite deposits on Earth, including published data from Southern California and South Africa. The chemical signatures closely matched, strengthening the case that the Martian rocks formed through rainfall-driven weathering rather than volcanic or hydrothermal processes, according to the new study.

One lingering mystery the team is still trying to solve is where the rocks came from.

There is no obvious nearby bedrock source, according to the study. The closest potential origin lies about 1.2 miles (2 kilometers) away, where orbital data shows signatures consistent with kaolinite in large chunks of fractured rock created by ancient impacts. Researchers also point to areas along the stretches of Neretva Vallis, a river channel that once flowed into Jezero crater.

"They're clearly recording an incredible water event, but where did they come from?" Horgan said in the statement. The rocks may have been carried into the crater by ancient rivers or blasted there by meteorite impacts, he added. "We're not totally sure."

These findings are described in a paper published in December of 2025 in the journal Nature Communications Earth & Environment.

Sharmila Kuthunur is an independent space journalist based in Bengaluru, India. Her work has also appeared in Scientific American, Science, Astronomy and Live Science, among other publications. She holds a master's degree in journalism from Northeastern University in Boston.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.