One of the most promising Earth-like worlds may not have an atmosphere after all

"We reported hints of methane, but the question is, 'is the methane attributable to molecules in the atmosphere of the planet or in the host star?'"

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

New observations of one of the famous TRAPPIST-1 planets are once again teasing scientists with tantalizing clues about a world that may — or may not — harbor an atmosphere capable of sustaining life-friendly liquid water.

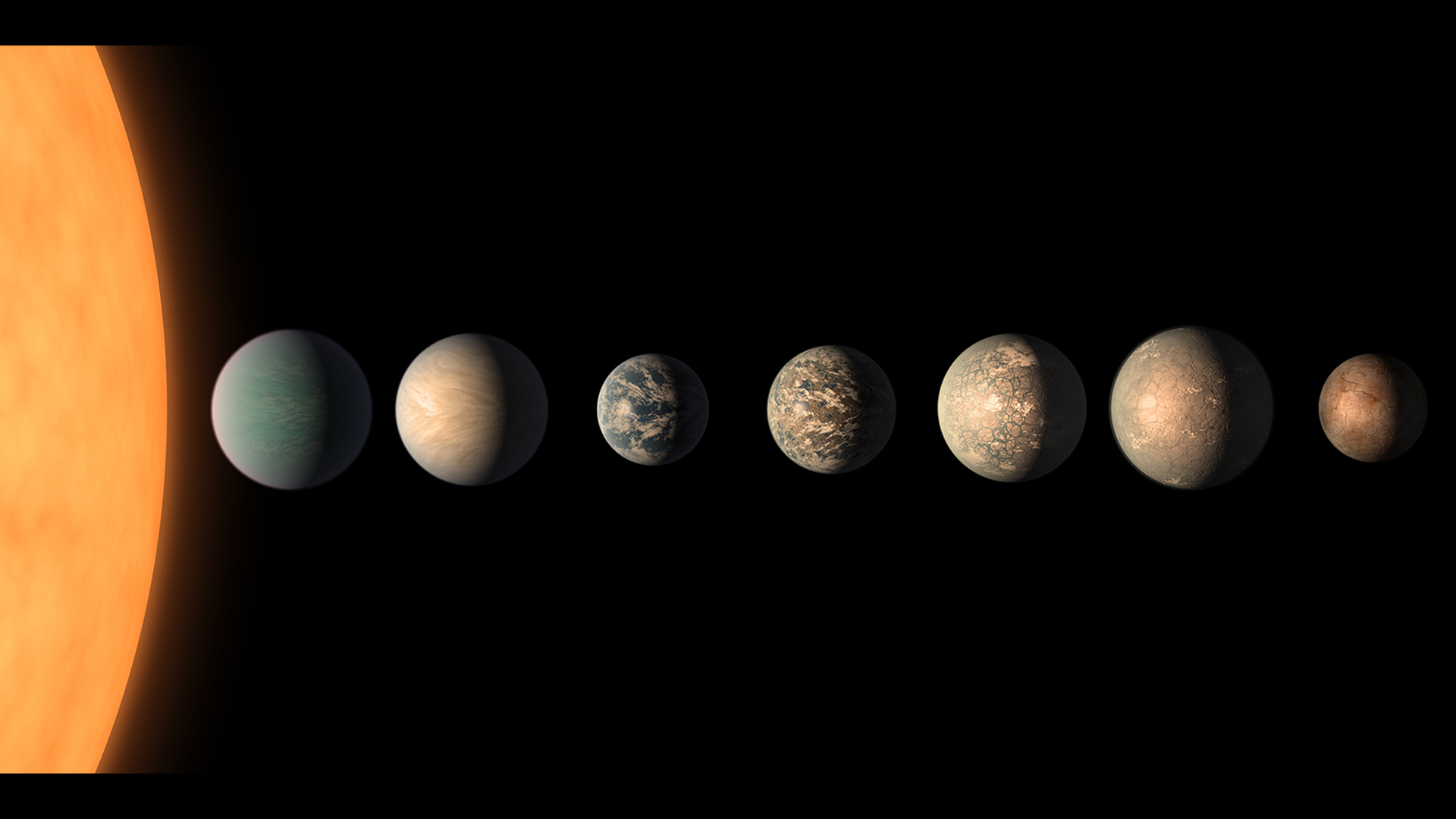

TRAPPIST-1e is one of seven Earth-size exoplanets tightly packed around a cool red dwarf star smaller and dimmer than our sun that's about 40 light-years away. It orbits in the system's "habitable zone," where temperatures could allow liquid water to exist — but that's only if the planet has an atmosphere. Early James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) observations even hinted at a possible atmosphere, revealing faint signatures of methane, which, on Earth, results from living organisms and is tied to complex chemistry on Saturn's haze-shrouded moon Titan.

But those first glimmers, scientists now say, were likely misleading.

"Based on our most recent work, we suggest that the previously reported tentative hint of an atmosphere is more likely to be 'noise' from the host star," Sukrit Ranjan, an assistant professor at the University of Arizona Lunar and Planetary Laboratory, said in a statement. "However, this does not mean that TRAPPIST-1e does not have an atmosphere — we just need more data."

The new paper uses detailed computer simulations to test whether TRAPPIST-1e could realistically maintain a methane-rich, Titan-like atmosphere. The results suggest methane on a world orbiting a small, active red dwarf star like TRAPPIST-1 would be destroyed much faster than on Titan — too quickly for any plausible geological process to replenish it.

The latest findings build on two papers published in September that analyzed the JWST's 2023 observations of TRAPPIST-1e. During four separate transits when the planet crossed the face of its star, the JWST's Near-Infrared Spectrograph (NIRSpec) instrument recorded subtle changes in starlight that could, in principle, reveal atmospheric chemicals. The data were consistent with an atmosphere dominated by nitrogen and methane and lacking carbon dioxide, effectively ruling out a Venus- or Mars-like atmosphere.

But the signals varied significantly from transit to transit, hinting that the measurements were being contaminated by the star itself. TRAPPIST-1 is smaller, cooler and far dimmer than our sun, cool enough that gas molecules, including methane, can form in the star's own atmosphere.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"We reported hints of methane, but the question is, 'is the methane attributable to molecules in the atmosphere of the planet or in the host star?'" Ranjan said in the statement.

In the paper, Ranjan and his team modeled how long methane could realistically survive in TRAPPIST-1e's environment. They found that while Titan's methane can persist for 10 million to 100 million years, methane on TRAPPIST-1e would last only about 200,000 years. The planet receives far more ultraviolet radiation than Titan, causing methane to be broken apart thousands of times faster, the study notes.

That makes it extraordinarily unlikely that scientists would catch the planet during a methane-rich phase unless methane were being replenished at extreme, continuous rates, the researchers say. Maintaining Titan-like levels would require TRAPPIST-1e to outproduce Titan in methane generation, an implausible scenario that would demand nonstop global volcanism, catastrophic methane release from an icy interior, or constant planetary resurfacing. Even under generous assumptions, these processes cannot fully account for the required methane supply, the study notes.

As a result, the team concludes that more rigorous analysis and additional observations are needed to determine whether TRAPPIST-1e has any atmosphere at all, and whether the JWST's tentative methane hints originate from the planet or are simply artifacts of the star.

"The basic thesis for TRAPPIST-1e is this: If it has an atmosphere, it's habitable," Ranjan said in the statement. "But right now, the first-order question must be, 'Does an atmosphere even exist?'"

Despite the challenges, TRAPPIST-1e remains one of the most promising potentially habitable worlds beyond our solar system. However, JWST, designed before the first exoplanet was discovered, is operating at the limits of its sensitivity when probing the atmospheres of Earth-sized planets.

Future instruments may help disentangle the confusing signals. NASA's upcoming Pandora mission, scheduled for launch in 2026, will observe stars and planets simultaneously to better separate stellar and atmospheric features.

The researchers are also planning a rare dual-transit observation in which TRAPPIST-1e and the innermost planet TRAPPIST-1b cross the star together. TRAPPIST-1b is known to lack an atmosphere, so comparing its "clean" signal to TRAPPIST-1e's could reveal which features belong to the star and which — if any — arise from TRAPPIST-1e's atmosphere, scientists say.

"These observations will allow us to separate what the star is doing from what is going on in the planet's atmosphere — should it have one," said Ranjan.

The paper about these results was published on Nov. 3 in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

Sharmila Kuthunur is an independent space journalist based in Bengaluru, India. Her work has also appeared in Scientific American, Science, Astronomy and Live Science, among other publications. She holds a master's degree in journalism from Northeastern University in Boston.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.