How are gas giant exoplanets born? James Webb Space Telescope provides new clues

Relatedly, astronomers may have just pushed the upper size limit of what counts as a planet.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Astronomers may have just pushed the upper size limit of what counts as a planet, thanks to new insights into how giant worlds form.

New observations from NASA's James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) suggest that even extremely massive gas giants — once thought too large to form like ordinary planets — may grow through the same basic process, shifting how scientists differentiate massive planets from brown dwarfs.

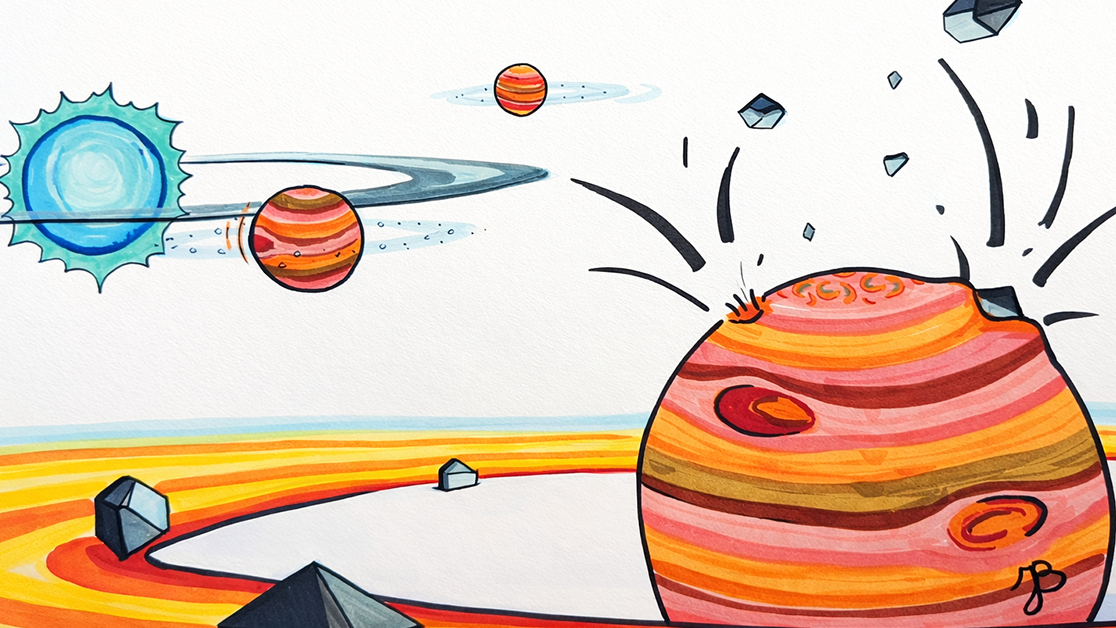

The findings come from a close look at the HR 8799 system, a young, sun-like star about 133 light-years from Earth that hosts four enormous gas giants orbiting far from their parent star. Each world is between five and ten times the mass of Jupiter — the largest planet in our own solar system — placing them near the fuzzy boundary between planets and brown dwarfs, which are substellar objects that fuse deuterium, rather than hydrogen like stars, earning them the nickname "failed stars," according to a statement from the University of California, San Diego.

Article continues belowFor years, astronomers have debated whether planets this massive could form through core accretion, the slow, bottom-up process in which solid material clumps together into a dense core that then pulls in vast amounts of gas. At extreme orbital distances, where material is sparse and protoplanetary disks fade quickly, many researchers thought this mechanism simply wouldn't allow enough time for these planets to grow so large.

To test that assumption, the research team used the JWST's powerful infrared spectrographs to analyze the chemical makeup of the planets' atmospheres. Instead of focusing on common gases like water vapor or carbon monoxide, the scientists searched for sulfur-bearing molecules — elements that typically begin as solid grains in a young protoplanetary disk and thus suggest the planet formed through core accretion, according to the statement.

The spectral data provided by the JWST revealed hydrogen sulfide in the atmosphere of HR 8799 c, one of the system's inner giants, providing strong evidence that the planet formed by first assembling a solid core before rapidly accreting gas. That chemical fingerprint is otherwise difficult to explain if the planet instead formed through a rapid, star-like collapse of gas. The team also found that the planets were more enriched in heavy elements, like carbon and oxygen, than their star, further supporting that they formed as planets.

"With the detection of sulfur, we are able to infer that the HR 8799 planets likely formed in a similar way to Jupiter despite being five to ten times more massive, which was unexpected," Jean-Baptiste Ruffio, lead author of the study, said in the statement.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Therefore, the study suggests that core accretion can operate efficiently even at extreme masses and distances, expanding the known limits of the planet-building process. If confirmed in other systems, the finding could force astronomers to rethink where — and how — the line between giant planets and brown dwarfs is drawn.

Their findings were published Feb. 9 in the journal Nature Astronomy.

Samantha Mathewson joined Space.com as an intern in the summer of 2016. She received a B.A. in Journalism and Environmental Science at the University of New Haven, in Connecticut. Previously, her work has been published in Nature World News. When not writing or reading about science, Samantha enjoys traveling to new places and taking photos! You can follow her on Twitter @Sam_Ashley13.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.