Astronomers may have spotted the 1st known 'superkilonova' double star explosion

"We do not know with certainty that we found a superkilonova, but the event nevertheless is eye-opening."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Astronomers may have discovered the first example of an explosive cosmic event called a "superkilonova," in the form of a gravitational wave signal detected on Aug. 18, 2025.

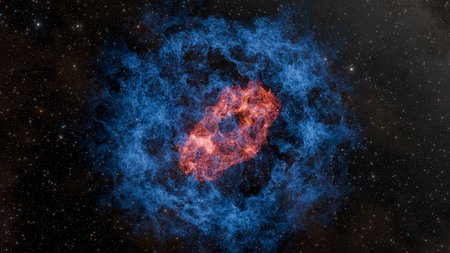

A kilonova describes the explosion generated when two neutron stars — stellar remnants left behind when massive stars die — slam together, creating the only environment in the known universe violent enough to forge elements heavier than iron, such as the gold and silver in your jewelry box.

Superkilonovas differ because they begin with the supernova explosion that marks the death of a star and the birth of two neutron stars, not one. These extreme dead stars then spiral together and merge, creating a scream of gravitational waves and a blast of electromagnetic radiation.

Article continues belowThus far, astronomers have made the unambiguous detection of just one kilonova when, in 2017, the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-wave Observatory (LIGO) and its European partner, Virgo, detected the gravitational wave signal known as GW170817. This event was then seen in electromagnetic radiation by a host of space and ground-based telescopes, instruments of "traditional astronomy."

Thus, scientists were already excited when LIGO and Virgo "heard" a signal designated AT2025ulz, which seemed to be the second detection of a neutron star merger. However, the situation soon seemed to take on added complexity. After the detection, an alert was sent out to astronomers across the globe, with the Zwicky Transient Facility (ZTF), a survey camera at Palomar Observatory in California, the first to spot a rapidly fading red object 1.3 billion light-years away. That's around the same location as the source of the gravitational waves.

"At first, for about three days, the eruption looked just like the first kilonova in 2017," study lead author Mansi Kasliwal, an astronomy professor at the California Institute of Technology, said in a statement. "Everybody was intensely trying to observe and analyze it, but then it started to look more like a supernova, and some astronomers lost interest. Not us."

Kasliwal and colleagues began to realize that what this event seemed to be was a kilonova stemming from a supernova explosion that's obscuring the view of astronomers. That would make AT2025ulz the result of a superkilonova, a type of powerful cosmic event long hypothesized but never before detected.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

A very strange signal

Following the detection of gravitational waves from this event, further investigation by several other telescopes, including the W. M. Keck Observatory in Hawai'i and the Fraunhofer telescope in Germany, revealed that the burst of light associated with AT2025ulz faded rapidly, leaving a glow in red wavelengths of light.

That was exactly the same pattern the electromagnetic signal associated with GW170817 had followed in 2017. This red glow is the result of heavy elements like gold around the kilonova blocking short-wavelength blue light but allowing longer-wavelength red light through. So far, so kilonova.

However, days after the explosion, AT2025ulz began to brighten and turn blue with evidence of hydrogen emissions appearing. These are characteristics of supernovas, not kilonovas. The problem is, while supernovas do generate gravitational waves, unlike a kilonova, a supernova 1.3 billion light-years away shouldn't be able to generate gravitational waves strong enough to be detected by LIGO.

While several astronomers were ready to conclude that AT2025ulz was just a run-of-the-mill supernova (if there is such a thing as a run-of-the-mill exploding star!), Kasliwal and team had noticed clues that indicated this was a very special event indeed. Specifically, the gravitational wave signal indicated that one of the neutron stars involved in the merger was less massive than the sun. Neutron stars are generally between 1.2 and two times the mass of the sun. This implied to the team that one or two small neutron stars might have merged to produce a kilonova.

Not all neutron stars are created equal

When stars with around 10 times the mass of the sun exhaust their fuel for nuclear fusion, their cores collapse under their own gravity, sending shockwaves rippling out that trigger a supernova explosion and blow away the outer layers of that star.

The result is a stellar core with a mass between 1.2 and 2 times the mass of the sun crammed into a diameter of around 12 miles (20 kilometers), packed with the densest matter in the known universe. However, scientists have theorized two ways in which some neutron stars could be created that are smaller than 1.2 solar masses.

The first scenario of undermassive neutron star creation suggests that, if a star that is spinning rapidly undergoes a supernova explosion, it could split into two sub-solar-mass neutron stars, a process called fission. In the second scenario, a rapidly spinning star undergoes a supernova explosion, but the resulting neutron star is surrounded by a disk of material that then gathers to form another neutron star, in a way similar to how planets form around infant stars.

In both cases, these neutron stars emit gravitational waves as they swirl around each other, carrying angular momentum away from the system. This causes the neutron stars to spiral together, collide and merge, churning out heavy elements. This would result in the red glow seen by the telescopes chasing AT2025ulz.However, the view of the kilonova was eventually obscured by the expanding shell of debris ejected by the supernova as it created the twin neutron stars.

"The only way theorists have come up with to birth sub-solar neutron stars is during the collapse of a very rapidly spinning star," team member Brian Metzger of Columbia University said in the same statement. "If these 'forbidden' stars pair up and merge by emitting gravitational waves, it is possible that such an event would be accompanied by a supernova rather than be seen as a bare kilonova."

Unfortunately, there currently isn't enough data to confirm that this is a superkilonova. The only way to do this is to gather more information.

"Future kilonovae events may not look like GW170817 and may be mistaken for supernovae," Kasliwal said. "We can look for new possibilities in data like this from ZTF as well as the Vera Rubin Observatory, and upcoming projects such as NASA's Nancy Roman Space Telescope, NASA's UVEX, Caltech's Deep Synoptic Array-2000, and Caltech's Cryoscope in the Antarctic. We do not know with certainty that we found a superkilonova, but the event is nevertheless eye-opening."

The team's research was published Dec. 15 in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. whose articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space, Newsweek and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University. Follow him on Twitter @sciencef1rst.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.