James Webb Space Telescope discovers what remains after two stars collide and explode as a red nova

"Until now, it was unknown what type of star would remain after the merger."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Astronomers have discovered what kind of stellar body is left after two stars collide and merge to generate an explosion called a "luminous red nova." Using the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), the scientists discovered that the result of this merger event, which triggers a bright burst of light, is a supermassive star similar to a red supergiant star, and also found that these stellar mergers could have provided the raw materials needed for life.

Though many astronomical events occur over cosmic timescales of thousands or even millions of years, transient events like supernova explosions, the merger of black holes, and the collision and fusion of stars, as in the case of luminous red novas, occur over much shorter periods, from fractions of a second to decades. That gives astronomers the opportunity to study these events in "real time" as they develop.

"We don't normally witness the evolution of a system over millions of years, but these pairs of stars are experiencing the final moments before their collision, which instead occurs much more rapidly," research team leader Andrea Reguitti of the Istituto Nazionale Di Astrofisica (INAF) said in a statement. "The resulting transient, in fact, has evolutionary times comparable to those of a supernova — that is, a few months."

Reguitti set about answering the question of what remains after the luminous red nova fades away and the two stars have merged into a single object by studying nine different luminous red novas found in archival data. These transients have brightnesses in between that of classical novas, triggered when a white dwarf hoards material from a companion star thus sparking a runaway nuclear explosion, and supernovas that mark the death of a massive star and the birth of a black hole or a neutron star. The masses of stars involved in the mergers that trigger the formation of a luminous red nova can range from less than that of the sun to up to 50 times that of our star.

Of the nine luminous red novas examined, the team found that only two told the entire story of these powerful merger events. These were AT 2011kp, which was spotted in 2011 in a galaxy located around 25 million light-years away, and AT 1997bs, which erupted in a galaxy located 31 million light-years from Earth.

"In some cases, analyzing archival images from major space telescopes taken years before the event has allowed us to identify the progenitor, that is, study the system as it was before the merger, and therefore understand what types of stars were involved," Reguitti said. "However, until now, it was unknown what type of star would remain after the merger."

To determine the nature of the stellar body left behind by these merger events, the team had to observe them several years after the initial event. That is because when stars merge to create a luminous red nova, they eject a vast amount of stellar material. That gives rise to the brightest phase of these transients (changes in brightness), but the bright and dense shell of matter also obscures the view of the created stellar body. As every luminous red nova can eject dust equivalent to 300 times the mass of Earth, it is easy to see how the initial stages of these events would be difficult to observe through all of that material.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

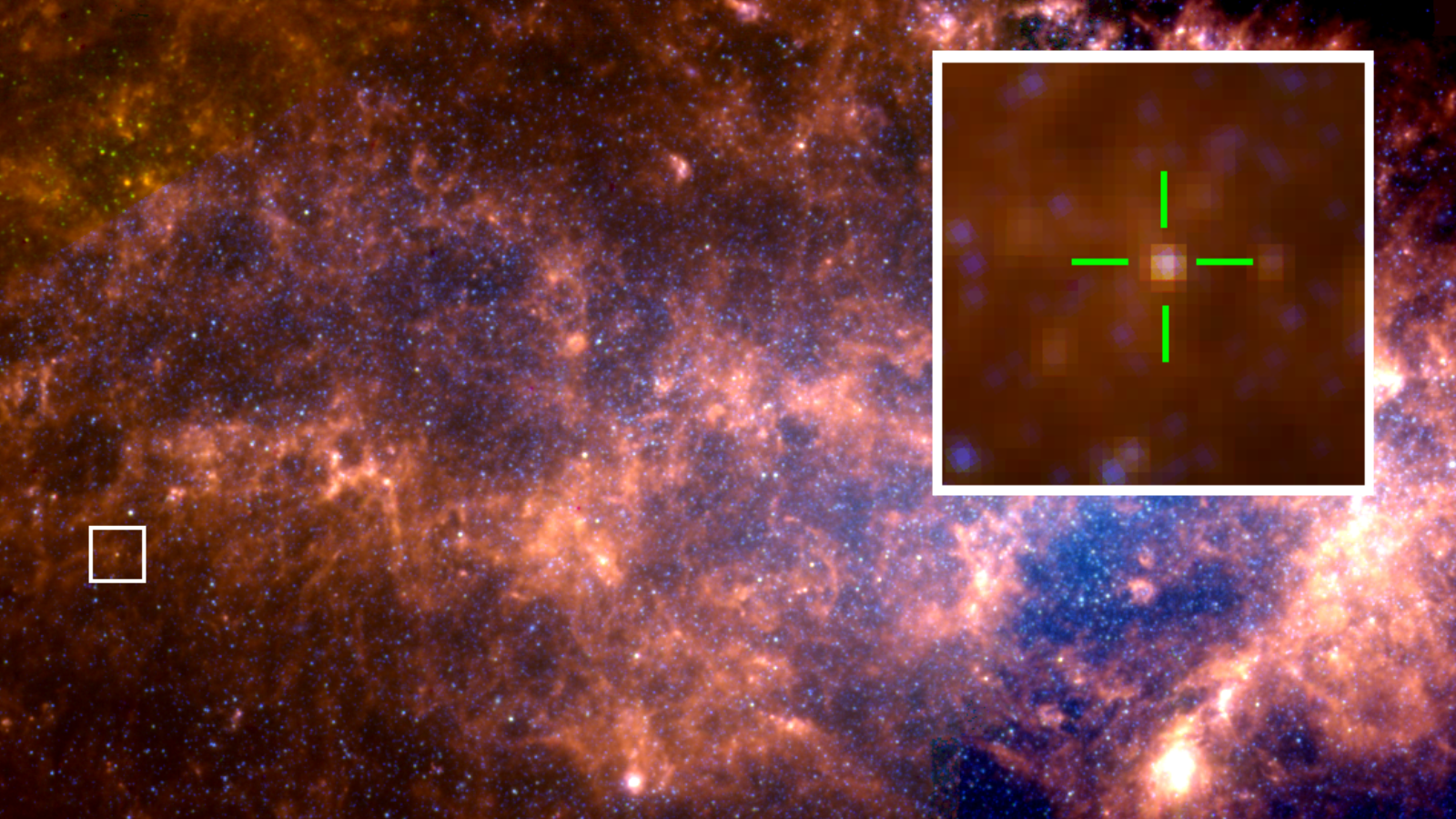

This investigation also required a space telescope powerful enough to observe distant galaxies and distinguish individual stars. That is where the JWST came in. Using infrared data gathered by the JWST in 2023 and 2024, in addition to visible light images collected by Hubble and the Spitzer Space Telescope, the team took another look at their selected luminous red novas, observing AT 2011kp as it was 12 years after the stellar merger event took place, while AT 1997bs was seen as it was after 27 years of evolution.

This revealed a stellar object very similar to a red supergiant star, a body hundreds of times the size of the sun, which, if placed at the heart of our solar system, would engulf the rocky inner planets and graze the orbit of Jupiter. Despite their immense size, the created stars were much cooler than the sun, with surface temperatures of between 5,840 degrees Fahrenheit and 6,740 degrees Fahrenheit (3,200 and 3,700 degrees Celsius) compared to the sun's surface temperature of around 10,300 degrees Fahrenheit (5,700 degrees Celsius).

"We didn't expect to find this type of object as a result of the merger," team member Andrea Pastorello, also of the INAF, said. "Rather, we would have expected that the system, going from two stars of a certain mass to a single one with a mass almost equal to the sum of the two (net of the material expelled by the collision), would have stabilized on a hotter and more compact source."

The impressive observing power of the JWST also allowed the researchers to study the chemicals that comprise the dust surrounding this newborn superstar. They found that this dust was made up of mostly carbon compounds like graphite. These compounds are important building blocks for living things, and with luminous red novas making such a significant contribution to interstellar dust, these events could have also played a key role in supplying the raw materials needed for life on Earth.

"We are made of carbon compounds, the same carbon that this dust is rich in," Reguitti concluded. "It's a different way of telling the old story that we are 'stardust.'"

The team's research is set to be published in the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics.

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. whose articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space, Newsweek and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University. Follow him on Twitter @sciencef1rst.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.