Altair: A guide to the brightest star in Aquila

Altair is one of the three stars in the Summer Triangle asterism.

Altair is a bright star in the northern summer sky and is one of the three stars that form an astronomical asterism called the Summer Triangle.

Located in the constellation Aquila (the Eagle) Altair is 16.8 light-years from Earth, making it one of the closest stars visible to the naked eye. It's also the 12th brightest star in the night sky with an apparent magnitude of +0.76.

Altair is also rotating rapidly. At nearly 185 miles (300 kilometers) a second at the equator, one rotation takes about 9 to 10 hours. This motion flattens the star slightly by about 14% according to EarthSky.

Where is Altair located?

— Right ascension: 19h 50m 47.0s

— Declination: 08 degrees 52 minutes 06 seconds

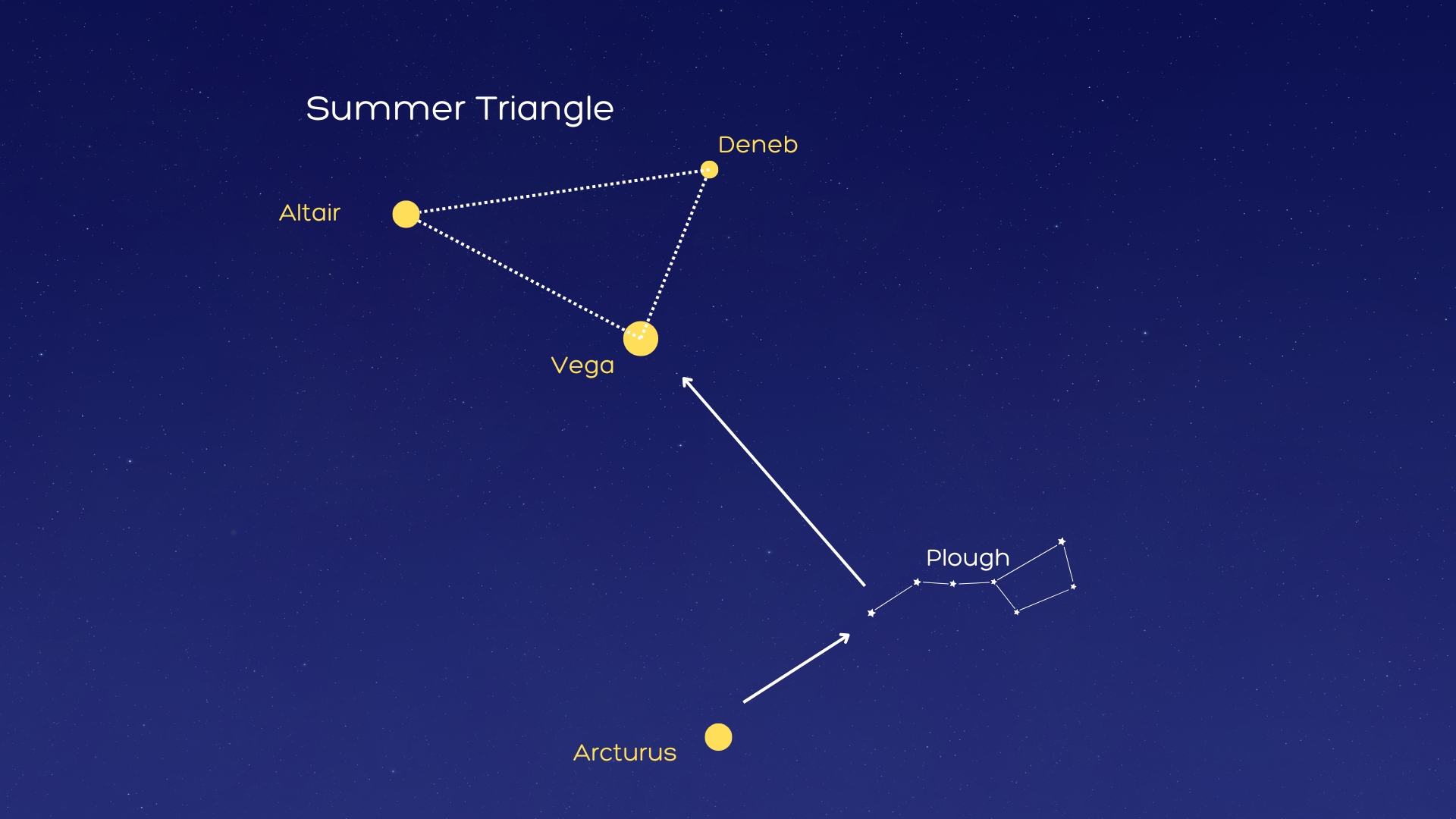

Altair is the brightest star in the constellation Aquila and one of the closest visible stars to Earth making it an ideal stargazing target. It forms part of the "Summer Triangle," an asterism that includes the stars Vega in Lyra and Deneb in Cygnus.

An easy way to find Altair is to first locate the Plough in Ursa Major, then adjust your gaze above and to the left to see the three stars that form the Summer Triangle. Altair is the leftmost star of the asterism.

The best time to look for Altair is in the southern sky during late summer or early fall evenings in the Northern Hemisphere. Altair stands out due to its brightness and position between two dimmer stars, Tarazed to the north-northwest and Alshain to the south-southeast, which forms a distinct line. This trio of stars makes Altair easy to spot within Aquila.

Altair in cultural

Altair's bright appearance drew the attention of many ancient cultures. While the name is Arabic (meaning flying eagle), it also was noticed in areas such as India, where Altair and two nearby stars were sometimes referred to as footprints of the god Vishnu .

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Chinese legend has a story involving the stars Altair and Vega. Every year on July 7, the story goes, Vega (a weaving girl) and Altair (a cowherd) meet each other after crossing a bridge — the Milky Way. This is celebrated in an event called the Qixi Festival .

The name Altair has also been used in the space industry, perhaps most notably with the proposed NASA Altair lunar lander. The name was released in 2007 for a vehicle being developed under the now-defunct Constellation human moon-to-Mars program .

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.

- Daisy DobrijevicReference Editor