How a Viral Comet Crash Into Jupiter Helped Popularize the Internet

A quarter century ago and thousands of miles away, a dramatic weeklong cosmic collision unfolded and helped the internet gain a foothold in people's lives.

That's according to an environmental historian who is investigating how cosmic events can shape human history. He has dug into NASA records, media reports and internet archives to understand how scientists and skywatchers followed 1994's weeklong barrage of Jupiter by fragments of the Shoemaker-Levy 9 comet over the young internet.

"We remember that now, if we remember it at all, as sort of a big event in science — it was the first collision ever predicted beforehand between named objects in the solar system," Dagomar Degroot, an environmental historian at Georgetown University told Space.com. "It was also a major cultural, even a political, even an environmental event."

Related: Comet Shoemaker-Levy 9's Epic Crash with Jupiter in Pictures

Traditionally, environmental history is limited to the environment of Earth proper and how it affects humans. But Degroot was inspired to begin expanding his approach by historical changes in climate that could be traced back to interactions between Earth and the sun. He has since broadened the scope of his research to other neighborhoods of the solar system, including Jupiter.

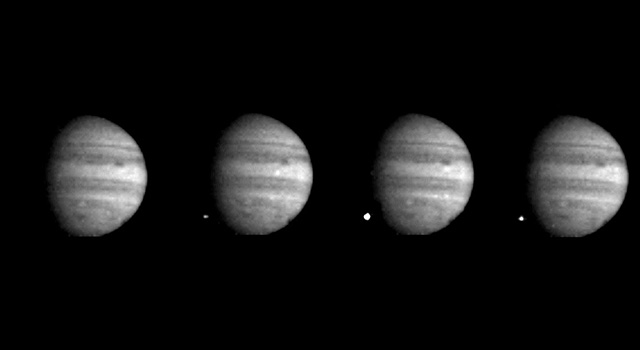

The comet scientists dubbed Shoemaker-Levy 9 flew too close to Jupiter in July 1992 and was shredded by the planet's massive gravity. But its true demise, which scientists were able to predict in advance, came two years later, in a dramatic weeklong series of impacts from the comet's fragments.

Although scientists knew that the impacts would be dramatic enough for skywatchers to see them with just a pair of binoculars, they couldn't predict precisely when during "impact week" in July 1994 each fragment would hit. So NASA and amateurs alike turned to the internet to share real-time updates about when to check in on the embattled gas giant. At the time, the World Wide Web was just 5 years old and hosted about 2,700 websites, Degroot said.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Shoemaker-Levy 9 lit up the tiny online community. Degroot found that nearly as many people as were hooked up to the internet at the time accessed NASA's resources about impact week. "This was really the first sort of viral event," Degroot said, and the internet fervor was covered by print media as well. "That really raised the profile of the internet, and not just for the online minority but also for the offline majority … it was pretty much everywhere."

The phenomenon continued, even after the impacts, with people creating and maintaining amateur pages about the event. "We see this astronomical — no pun intended — growth in the number of websites," Degroot said. "In terms of galvanizing the whole internet, I think that might have been unique to 1994." NASA responded by pivoting their approach to communications, replacing print mailings to media outlets with public announcements available online.

Of course, impact week alone can't take all the credit (or blame) for the internet's rise; the technology was ready to hit it big. "I'm not saying that everything is tied to the Shoemaker-Levy 9 collision," Degroot said. "But I do think it showed that the internet was viable as a tool for scholarship on the one hand, but also as a tool for connecting millions and millions of people to the work that scientists do, and ultimately to environmental change in this distant corner of the solar system."

In part, he suspects the collision's appeal may have been a matter of zeitgeist. During the 1980s, scientists pinned the dinosaurs' extinction to a cataclysmic impact. And the 25th anniversary celebrations of the moon landing in 1994 reminded bystanders of crater science conducted during the Apollo program. "Fundamentally, the timing was right in the sense that the idea that an asteroid or a comet could cause a catastrophe on Earth had been well established in popular culture," Degroot said.

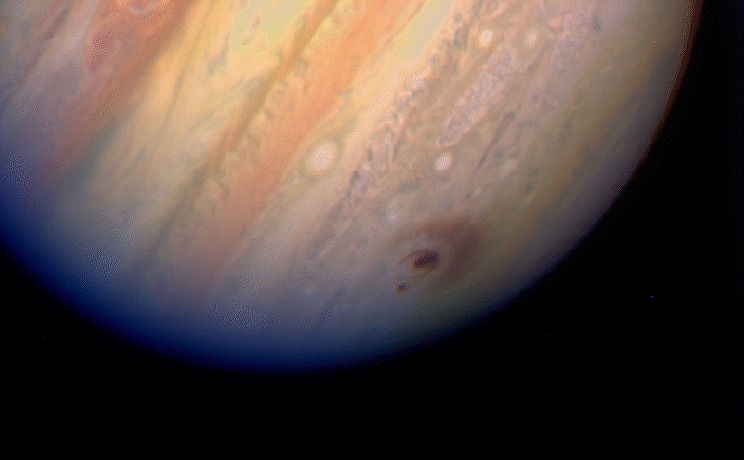

Seeing a series of impacts have such vivid consequences on another planet — a handful of the impact scars were the size of Earth, and they were by far the clearest features on the gas giant at the time — brought that point home for skywatchers at the time.

And just as the internet's legacy continues to grow and diversify, so may the impacts', Degroot said. Watching the impacts galvanized people to begin survey programs that hunt for space rocks near Earth, and having such a detailed map of threats has encouraged humans to look for opportunities as well. Now, some hope that nearby asteroids could offer water and metal resources that may reduce our need to exploit Earth.

"It may be that ultimately, this cataclysmic environmental change in a distant corner of the solar system will lead us to alter environments and preserve environments closer to home," Degroot said.

- Shoemaker-Levy 9's Co-Discoverer Still Chasing Comets, 20 Years Later

- Jupiter Just Got Hit by a Comet or Asteroid ... Again (Video)

- Jupiter's 7 Most Massive Mysteries

Email Meghan Bartels at mbartels@space.com or follow her @meghanbartels. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Meghan is a senior writer at Space.com and has more than five years' experience as a science journalist based in New York City. She joined Space.com in July 2018, with previous writing published in outlets including Newsweek and Audubon. Meghan earned an MA in science journalism from New York University and a BA in classics from Georgetown University, and in her free time she enjoys reading and visiting museums. Follow her on Twitter at @meghanbartels.