Venus may get a huge meteor shower this July, thanks to a long-ago asteroid breakup

But we likely won't be able to enjoy it here on Earth.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Venus could experience a dramatic meteor shower this summer, the result of the breaking apart of a nearby asteroid that has left a trail of dust in its wake.

The meteor shower is predicted to next take place on July 5, but observing it from Earth is going to be difficult. Only superbright fireballs, with a magnitude of around minus 12 to minus 15 — roughly the same brightness in our sky as the moon — will be visible from our planet.

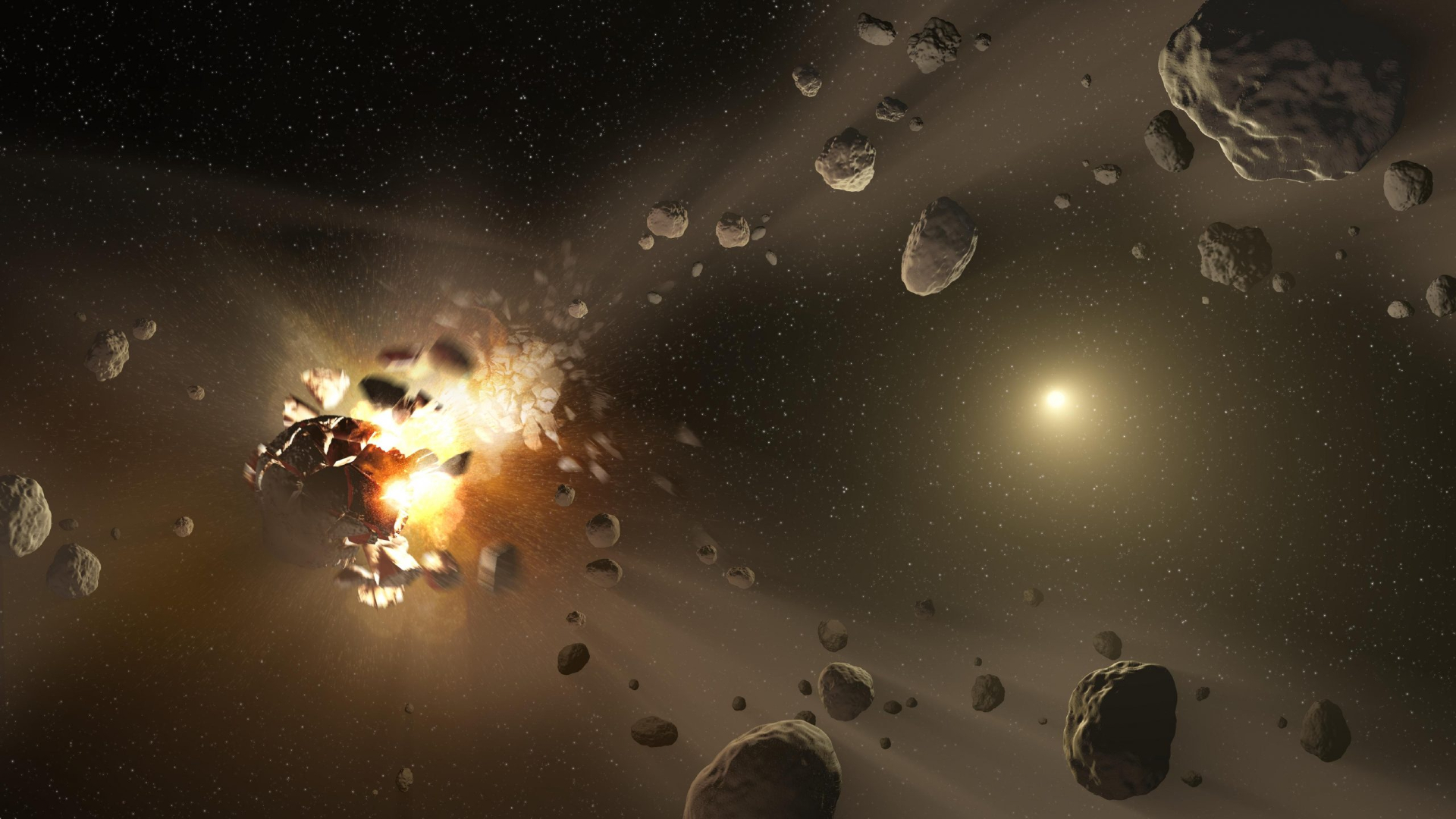

The origin of this proposed meteor shower is the result of a detective story involving two asteroids curiously sharing the same orbit, more or less. In 2021, a near-Earth asteroid was discovered on an orbit that brings it within 2 million kilometers (1.2 million miles) of Venus. Then, in April 2025, a second asteroid was found on almost exactly the same orbit.

Both asteroids, named 2021 PH27 and 2025 GN1, have the same spectral class (type X), meaning that they look the same when we measure their spectra. Also, their orbits are entirely inside that of Earth, meaning that they never intersect our planet's path and are not an impact risk. Asteroids on such orbits belong to what scientists refer to as the Atira group, and they are relatively rare.

Incidentally, the pair also have the fastest orbits ever measured for an asteroid in the solar system, taking just 115 days to complete one circuit around the sun.

The discovery of two asteroids that look the same while sharing almost the same orbit was too much of a coincidence for a team of astronomers led by Albino Carbognani of the Italian National Institute for Astrophysics (INAF). So they set about modeling the orbit of the asteroids going 100,000 years back into the past, to see if they could figure out the space rocks' origin.

The researchers suspected that the two asteroids were once a single asteroid that broke apart, but the simulations of their orbits revealed that at no point had they had come close enough to Earth, Venus or the sun to have been broken apart by gravitational tidal forces. The hypothesis seemed like a dead end.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Carbognani's team wasn't stumped for long, however. They noticed that the orbit of the two asteroids did change over the course of 100,000 years. At one point, it got as close to the sun — the point that astronomers refer to as perihelion — as 15 million kilometers (9 million miles).

That's about four times closer to the sun than Mercury orbits, on average.

Suppose, then, that the two asteroids were once a single body. So close to the sun, repeated heating would cause the surface of the parent asteroid to crack, weakening its interior rigidity, especially if the rock were little more than a loosely held together rubble pile.

The parent asteroid would have been rotating while it was heating up near perihelion. It absorbs heat on one side and, as it spins, it radiates excess heat away in another direction. The emission of this thermal radiation acts as a weak thrust that prompts the rotation of the asteroid to speed up — a phenomenon known as the YORP effect (in honor of Yarkovsk, O'Keefe, Radzievskii and Paddack, four scientists who were key to its discovery).

Carbognani's team suggests that, coupled with fractures on the surface weakening the asteroid's structure, the YORP effect was able to spin the parent asteroid fast enough that it broke apart into two pieces.

Their simulations suggest this could have happened between 17,000 and 21,000 years ago, which was the last time the orbit got as close as 15 million kilometers to the sun. If that's correct, then not enough time has passed for solar radiation to have cleared out all the dust sprayed into space by the asteroid breaking up.

"Considering that the orbits pass very close to Venus, it's natural to wonder whether very small fragments, on the order of a millimeter, generated by the fragmentation of the original body, could still be in orbit around the sun," said Carbognani in a statement. "Our simulations confirm that this is indeed possible."

The simulations show that Venus will next intercept the dust stream, which would have broadened out wide enough to get in the way of Venus, in July of this year. If this is correct, we can expect a meteor shower over Venus at that time.

While the vast majority of meteor showers on Earth are produced by dust left behind by the tails of comets, Carbognani draws a comparison with December's Geminid meteor shower.

"A well known case is that of the Geminids, generated by the asteroid Phaethon, and our results suggest a similar phenomenon could also occur on Venus," he said.

Seeing Venus' equivalent of the Geminids from Earth is going to be tough, however.

"To increase the probability of detection, the ideal option would be direct observation from Venus' orbit via a spacecraft," said Carbognani. Alas, there are currently no space missions operational at Venus, but the meteor shower could be observed in the future by Europe's EnVision, scheduled to launch for Venus in 2031 or 2032, or by NASA's DAVINCI and VERITAS missions, should they go ahead in the next decade.

The findings were reported on Jan. 17 in the journal Icarus.

Keith Cooper is a freelance science journalist and editor in the United Kingdom, and has a degree in physics and astrophysics from the University of Manchester. He's the author of "The Contact Paradox: Challenging Our Assumptions in the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence" (Bloomsbury Sigma, 2020) and has written articles on astronomy, space, physics and astrobiology for a multitude of magazines and websites.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.