The most exciting exoplanet discoveries of 2025

New discoveries and fresh looks at familiar worlds show how far exoplanet science has come — and how much remains unknown.

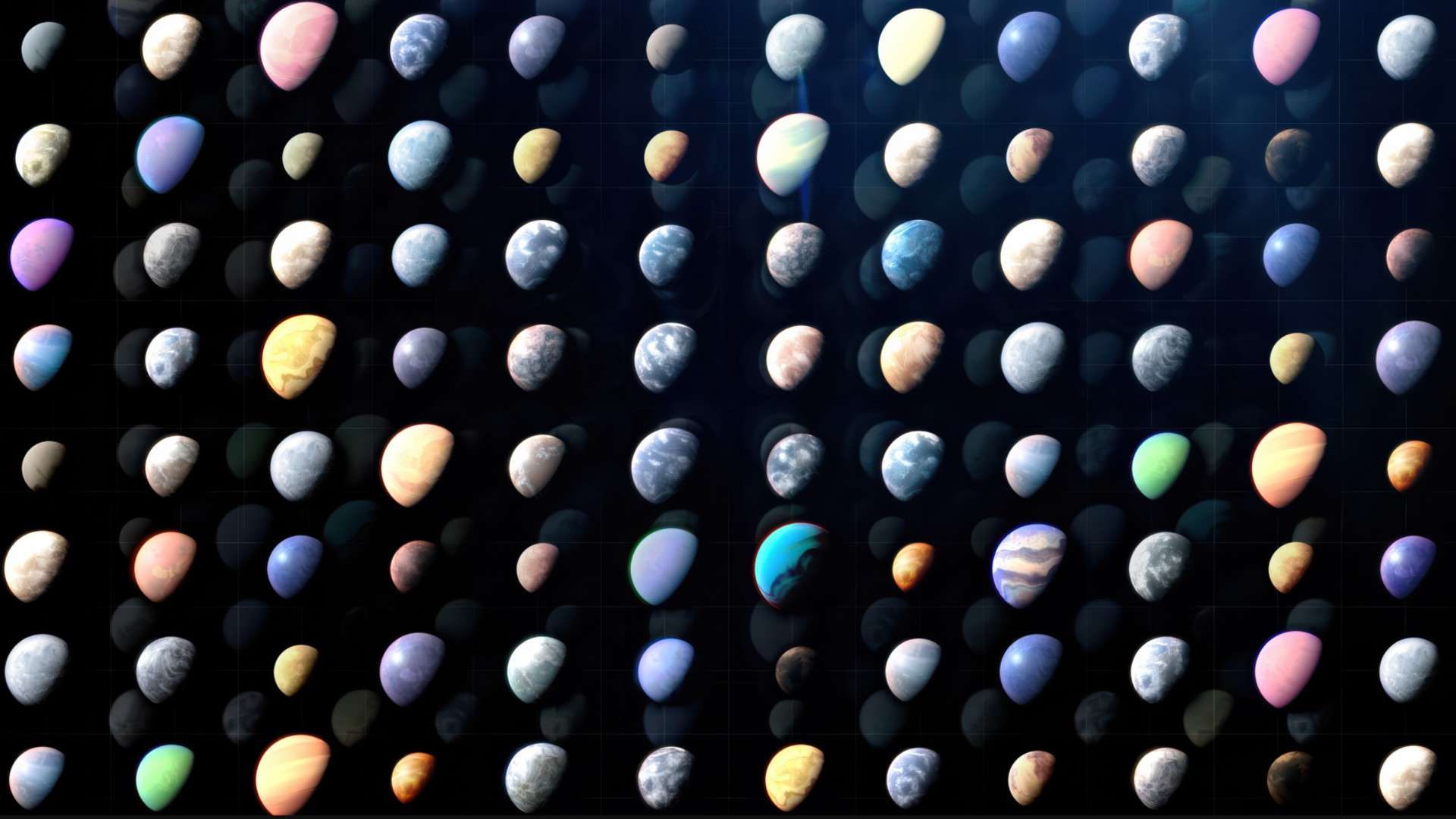

This year, the number of NASA-tracked confirmed worlds discovered beyond our solar system surpassed 6,000, and several thousand more await confirmation.

The milestone, reached just three decades after the Nobel Prize-winning discovery of the first planet orbiting a sunlike star in 1995, is largely the result of the planet-hunting power of NASA's Kepler space telescope and Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS).

The growing tally reflects how dramatically humanity's view of our home galaxy, the Milky Way, has expanded — and how diverse its planetary population has turned out to be.

Far from mirroring the relatively flat, orderly architecture of our own solar system, new observations and more detailed reexaminations of familiar worlds revealed entire classes of planets with no counterparts at home — super-Earths, mini-Neptunes and hot Jupiters — as well as worlds on contorted orbits that are forcing astronomers to rethink how planets form and evolve.

As the year comes to a close, here's a look back at some of the most intriguing, puzzling and rule-breaking exoplanets astronomers studied in 2025. These worlds illustrate both how far exoplanet science has come and how much there still is to learn.

"Tatooine" worlds

More "Tatooine-like" worlds leapt from science fiction into the exoplanet database this year, as astronomers identified multiple planets orbiting two suns — sometimes in configurations that challenge the basic rules of planetary formation.

The strangest of these worlds emerged in April, when a team reported the discovery of 2M1510 (AB) b, a planet orbiting two brown dwarfs, which are often called "failed stars" because they're not massive enough to ignite nuclear fusion.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Located about 120 light-years from Earth, the world orbits above and below the poles of its two stars, rather than along the usual flat plane. The discovery team inferred the planet's presence using the Very Large Telescope in Chile, after detecting an unusual backward wobble in the brown dwarfs' orbits. This was a gravitational clue that the researchers said could be explained only by a hidden, steeply inclined planet that was possibly knocked into place by a stellar flyby long ago.

Later in the year, a different team discovered three Earth-size planets orbiting the compact binary system TOI-2267, just 73 light-years from Earth. Using data from TESS, the team found that all three worlds transit both stars, even though such tightly bound stellar pairs are thought to be gravitationally unstable environments for planet formation.

Adding to the haul, two independent teams identified HD 143811 (AB) b, a massive planet that had been hidden in archival data for years. Captured by the Gemini Planet Imager on the Gemini South telescope in Chile, the world orbits a young twin-star system about 446 light-years from Earth. Though it's roughly six times the size of Jupiter, the planet is only 13 million years old and still glows with heat left over from its formation.

The alien world's host stars whirl around each other every 18 days, while the planet itself traces a slow, 300-year orbit around both. The contrast of a fast-dancing binary and a distant, lumbering giant poses a lingering mystery of how such a massive planet formed and survived in such a dynamically complex system.

The search for life on K2-18b

The exoplanet K2-18b arguably became one of 2025's loudest exoplanet flash points after renewed claims of possible life swiftly ignited scientific debate.

The world made headlines in April when a University of Cambridge-led team announced what it called its strongest evidence yet for potential biosignature gases in the planet's atmosphere. Using new transit spectra from the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), the researchers argued that the data were consistent with dimethyl sulfide, and possibly dimethyl disulfide — gases that on Earth are strongly associated with marine biology. The findings, the team argued, bolstered the case that the planet could support life on an ocean-covered world they described as potentially "teeming with life."

Within weeks, however, independent analyses challenged that interpretation. One group showed that nonbiological gases, including propyne, could reproduce the same spectral features without invoking life, while another concluded that the JWST signal was too noisy or too weak to draw definitive conclusions.

The debate also drew attention to the limits of JWST, which was conceived before the discovery of exoplanets and is now being pushed to the edge of its capabilities to study one.

Still, researchers emphasize that K2-18b remains a high-value target for understanding sub-Neptunes, a class of planets absent from our solar system. Additional JWST transits already in hand may yet clarify what, if anything, the planet's atmosphere is truly revealing.

"If the ultimate result of this story is that the public is more circumspect about future claims of life detection, that's not a terrible thing," Eddie Schwieterman, an assistant professor of astrobiology at the University of California, Riverside, who was not involved with the research, told Space.com.

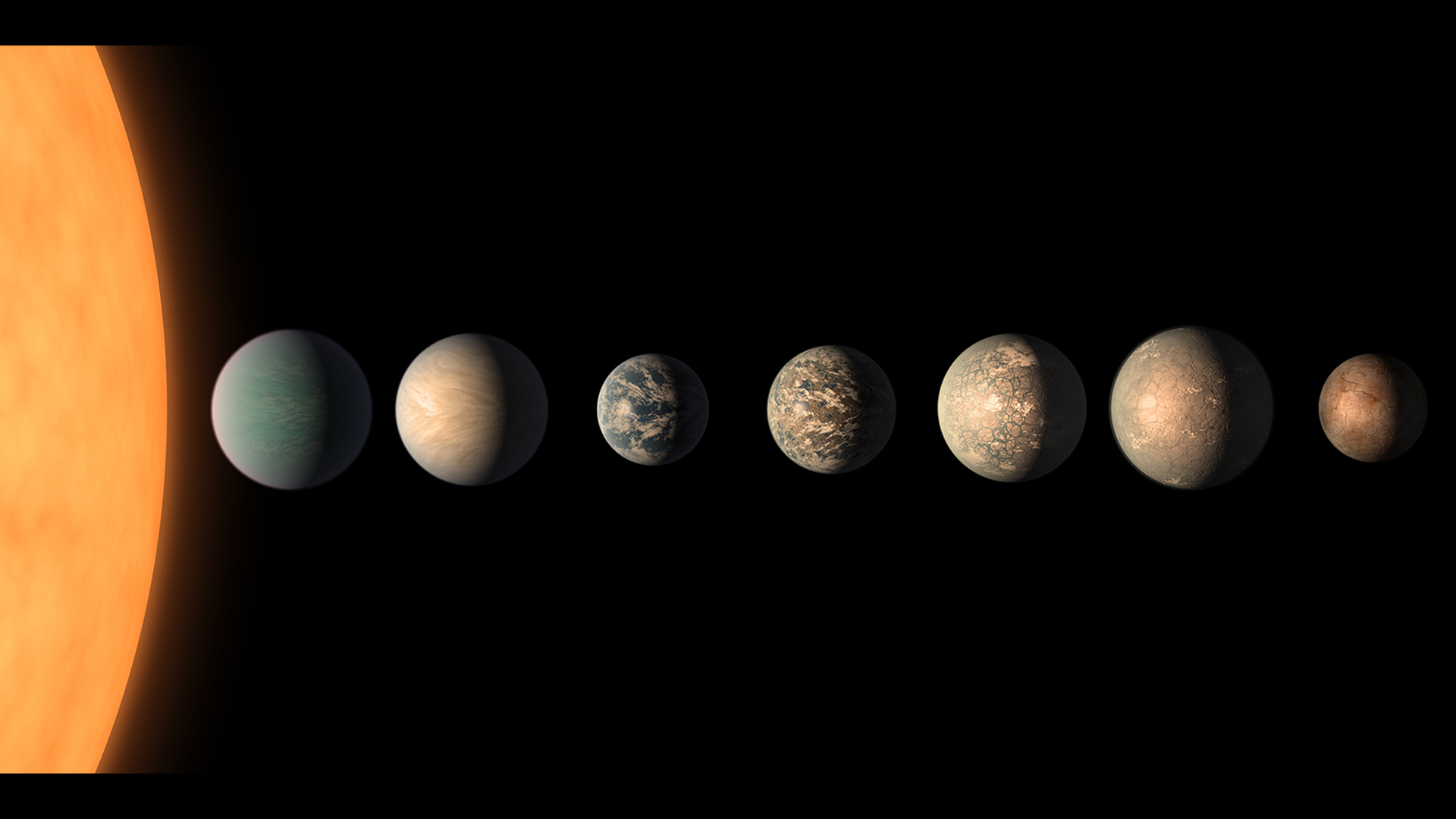

Dashed hopes for TRAPPIST-1e's habitability

New analyses of TRAPPIST-1e, one of seven Earth-size planets orbiting a cool red dwarf star about 40 light-years from Earth, suggest the planet may lack a substantial atmosphere, complicating hopes that it could support life-friendly liquid water.

Earlier JWST observations hinted at methane in the planet's atmosphere, raising the possibility of complex chemistry or even biological activity. Follow-up studies, however, indicated those signals were likely contaminated by the star itself.

Computer simulations showed that any methane on TRAPPIST-1e would be rapidly destroyed by intense ultraviolet radiation, surviving only about 200,000 years — not nearly long enough for geological processes to replenish it.

Variations in the signal from transit to transit further suggest that if an atmosphere exists at all, it remains extremely difficult to detect — a reminder that even the most promising worlds can defy easy answers.

A clearer look at Proxima Centauri

In 2025, astronomers sharpened their view of the planetary system around Proxima Centauri — the sun's closest stellar neighbor, which lies just 4.2 light-years away — thanks to a powerful new instrument designed to hunt worlds around small, cool stars.

The Near-Infrared Planet Searcher (NIRPS), a new high-resolution spectrograph installed at La Silla Observatory in Chile, delivered its first science results in July.

A team led by Alejandro Mascareño of the Institute of Astrophysics of the Canary Islands in Spain confirmed the presence of Proxima b, an Earth-size planet known to orbit within the star's habitable zone, thereby validating the instrument's capabilities.

NIRPS also confirmed a smaller planet, Proxima d, and helped rule out a previously claimed third world, thus refining the census of the nearest planetary system.

The results also marked a technical milestone. For the first time, astronomers reached the precision needed to detect the faint gravitational pull of small, rocky planets around red dwarf stars, which emit most of their light at infrared wavelengths — making instruments like NIRPS valuable in the search for Earth-like planets beyond our solar system.

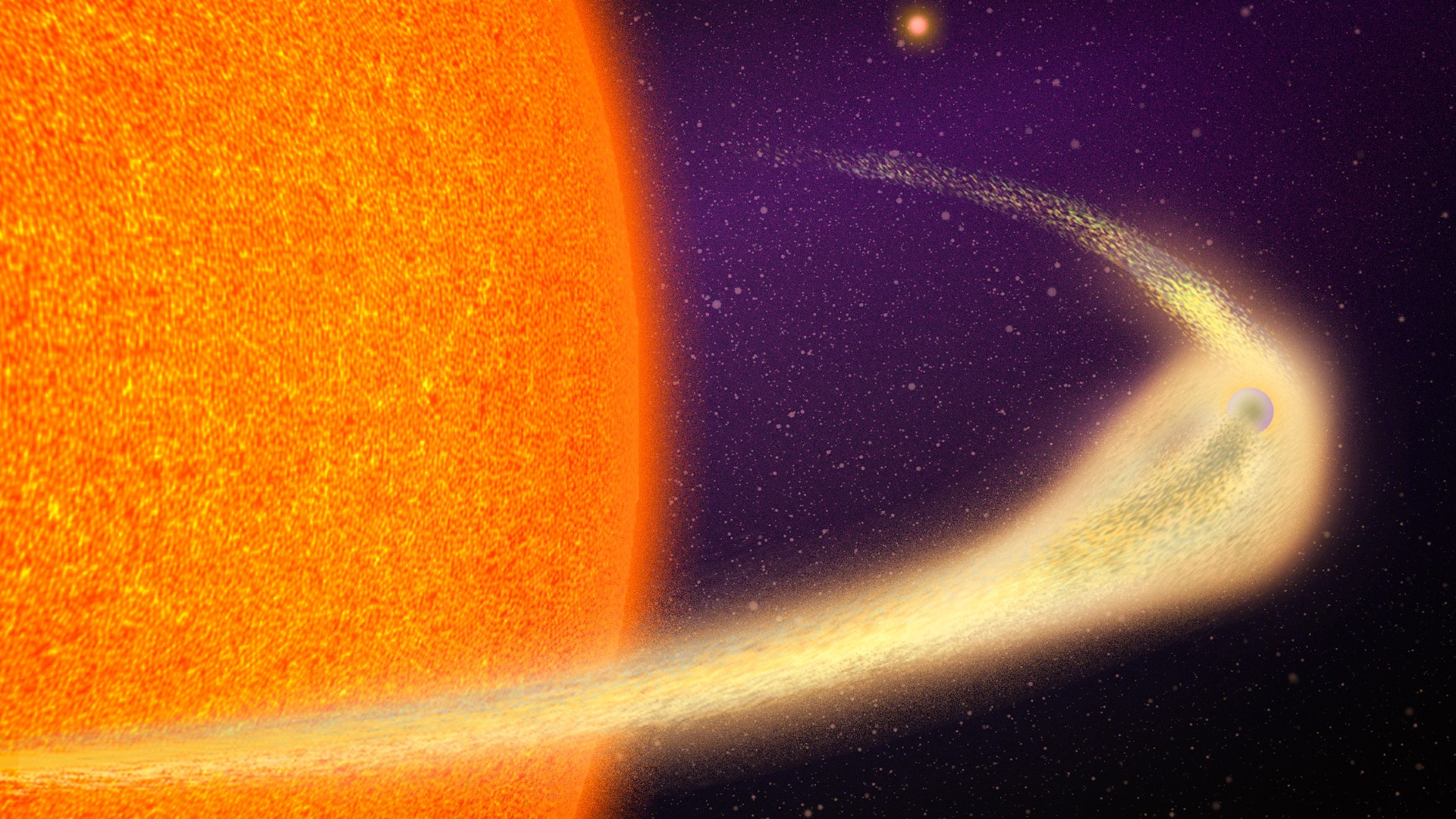

The tails of disintegrating worlds

This year, astronomers discovered rare exoplanets that orbit so close to their stars that they have long tails of material. These worlds are caught in a fleeting moment, in cosmic terms, before they disintegrate.

One such world, BD+05 4868 Ab, was spotted by TESS about 140 light-years from Earth, in the constellation Pegasus. The planet completes a full orbit every 30.5 hours, circling its star at a distance roughly 20 times closer than Mercury orbits the sun. At such proximity, intense stellar heat vaporizes material from the planet's surface, which then streams into space, forming a blazing, comet-like tail. That tail is enormous, stretching up to 5.6 million miles (9 million kilometers), or about half the planet's orbit.

The discovery team estimates that the planet sheds the equivalent of a Mount Everest's worth of material every orbit and could completely disintegrate within 1 million to 2 million years. The dust in the tail may contain material from the planet's crust, its mantle or even its core, which would give scientists a rare opportunity to study the internal composition of a distant world — something normally far beyond observational reach.

Another team used JWST to study a very different kind of planetary tail around the ultrahot Jupiter WASP-121b, also known as Tylos, located about 858 light-years from Earth. Instead of shedding rock, the planet is losing its atmosphere. JWST revealed two enormous helium tails spanning nearly 60% of the planet's orbit — one trailing behind, pushed back by stellar radiation and wind, and a second, rarer leading tail curved ahead of the planet, likely drawn inward by the star's gravity.

A lava world that refuses to go bare

Astronomers using JWST found an atmosphere clinging to a planet that, by all conventional rules, should be completely airless.

The world, TOI-561b, is a small, scorching lava planet that orbits one of the oldest stars in the Milky Way so closely that its year lasts less than a single Earth day.

Tidally locked, with one side permanently facing its star, the planet reaches surface temperatures of more than 3,140 degrees Fahrenheit (about 1,726 degrees Celsius) — hot enough to melt rock — and is old enough that any primordial atmosphere should have escaped long ago.

Yet JWST observations suggest the planet's dayside is cooler than expected for a bare, airless rock, pointing to the presence of a substantial atmosphere that may have persisted for billions of years and is redistributing heat around the planet.

If confirmed, the finding would mark the strongest evidence yet for a long-lived atmosphere on a hot, rocky world that is neither massive nor temperate, challenging assumptions about the extreme conditions in which planetary atmospheres can survive.

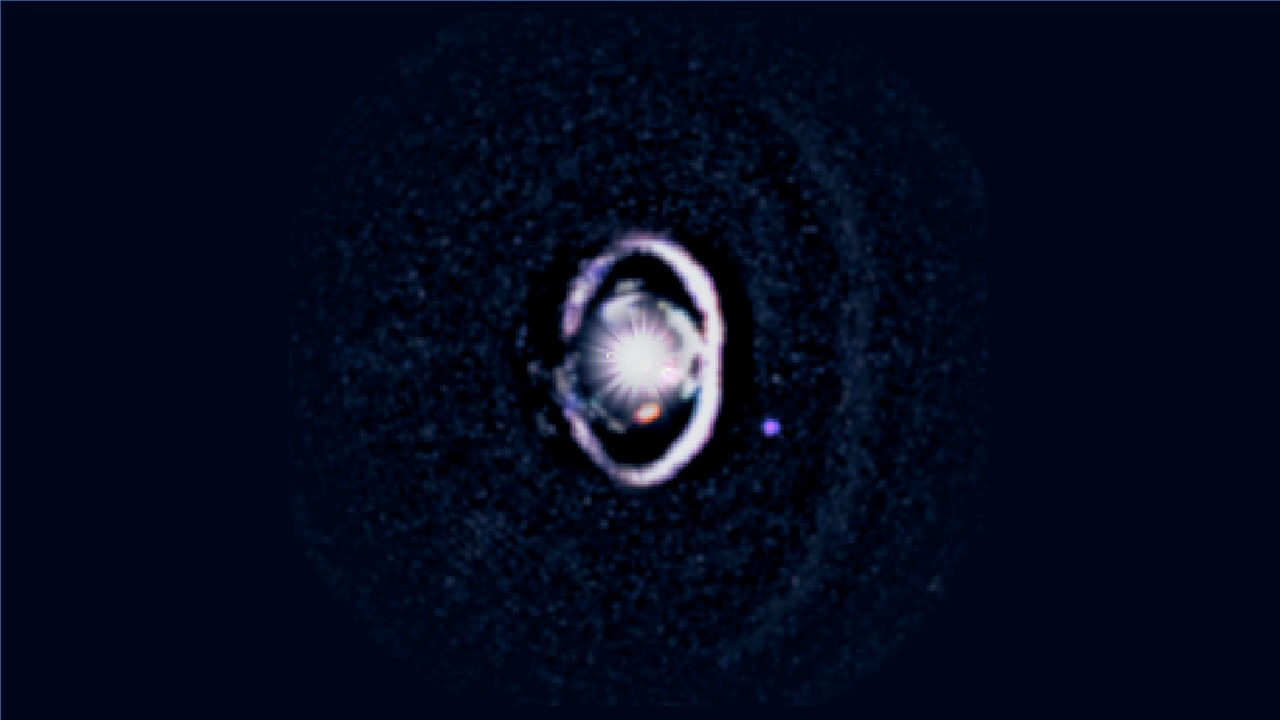

The birth and death of an alien world

This year, astronomers observed two cosmic moments that bookend the life of a planet.

In one study, astronomers captured a never-before-seen view of a planet forming about 437 light-years from Earth.

The observations, taken with the Magellan Telescopes in Chile and the Large Binocular Telescope in Arizona, show the alien world as a faint, purple dot embedded within a ring-shaped gap in a dusty disk around its star. The forming world, WISPIT 2b, is just 5 million years old, yet it is already about five times as massive as Jupiter, and it's sitting within a clearing in the disk as it gathers dust and gas to grow.

Astronomers have long suspected that such gaps mark the presence of newborn planets, but this is the first time one has been directly observed actively carving out its orbit. The team also identified a second candidate planet closer to the star, hinting that this system may be building multiple worlds at once.

Closer to Earth, another team captured a glimpse of a dead star's remains. Observations of the white dwarf LSPM J0207+3331, the dense remnant of a long-gone massive star about 145 light-years from Earth, reveal the ongoing destruction of a planetary relic — possibly a body roughly 120 miles (193 km) wide — being torn apart by the star's intense gravity.

Using telescopes in Chile and Hawaii, astronomers detected heavy elements recently deposited on the white dwarf's surface, which they say is evidence that the debris was accreted within the past 35,000 years and may still be falling in today.

The findings suggest that gravitational forces that shift as the star decays can destabilize surviving planets and smaller bodies such as asteroids, thereby triggering collisions and sending fragments spiraling inward to their destruction.

Sharmila Kuthunur is an independent space journalist based in Bengaluru, India. Her work has also appeared in Scientific American, Science, Astronomy and Live Science, among other publications. She holds a master's degree in journalism from Northeastern University in Boston.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.