We've officially found 6,000 exoplanets, NASA says: 'We're entering the next great chapter of exploration'

"There's one we haven't found — a planet just like ours. At least, not yet."

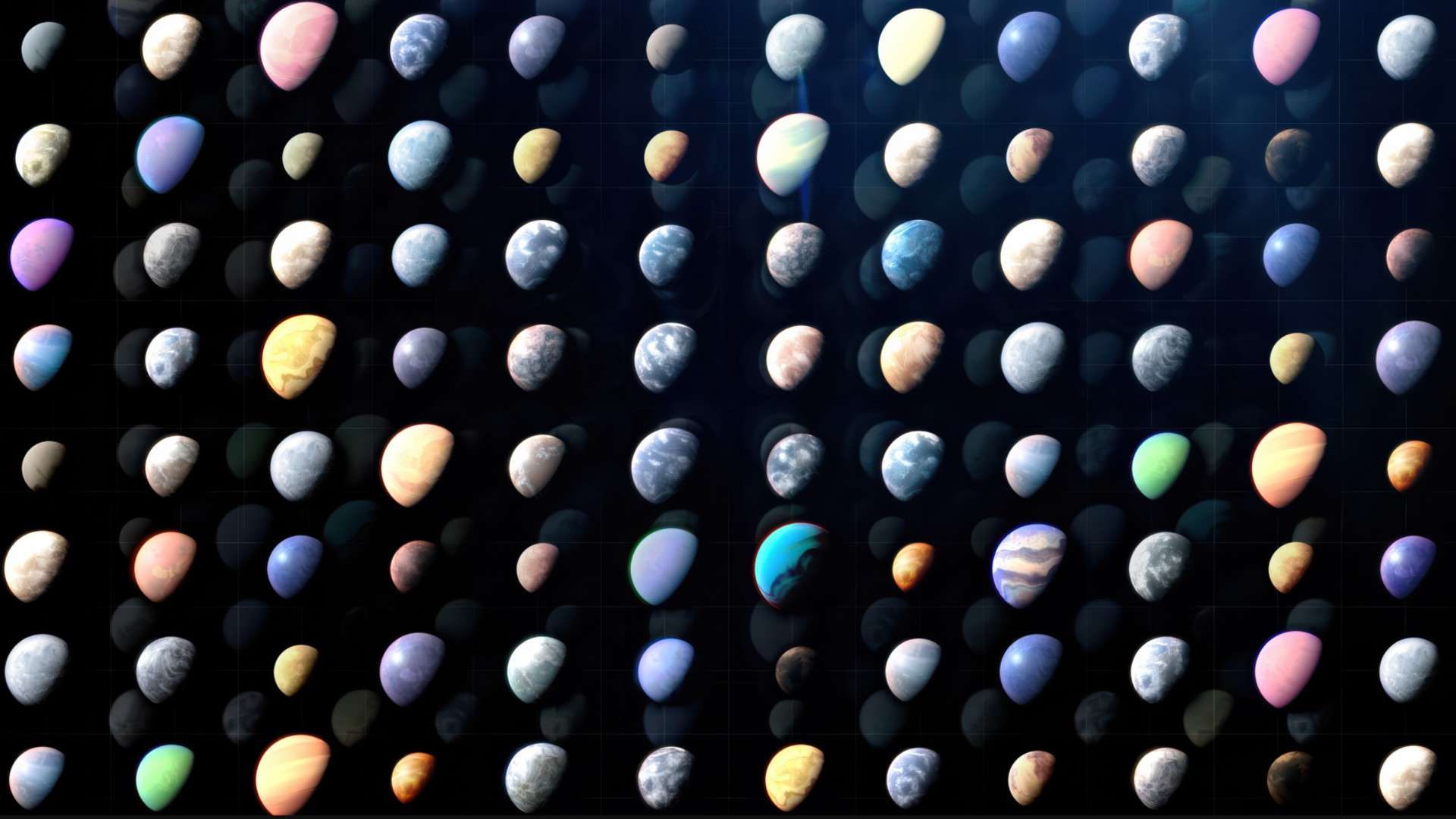

It might sound hard to believe, but NASA's exoplanet count just reached 6,000 — and that's with only about 30 years of hunting worlds beyond our solar system. In fact, only three years ago, that figure was at 5,000. At least at face value, the rate of discovery appears to be exponential — which is good, because, theoretically, there should be billions more worlds out there for us to locate.

"We're entering the next great chapter of exploration — worlds beyond our imagination," a narrator says in a NASA video about the milestone. "To look for planets that could support life, to find our cosmic neighbors and to remind us the universe still holds worlds waiting to be found."

The news was announced on Wednesday (Sept. 17), which is serendipitously close to the anniversary of when scientists confirmed the existence of the first exoplanet around a sun-like star: 51 Pegasi b. Discovered on Oct. 6, 1995 by astronomers Michel Mayor and Didier Queloz, 51 Pegasi b is a gas giant 0.64 times as massive as Jupiter that sits approximately 50 light-years from where you're sitting. (To be clear, the very first exoplanet discovery fell in 1992, but that one was around a spinning neutron star, or pulsar. And pulsars are pretty wild. 51 Pegasi b was the first more "normal" exoplanet to be identified.) The right thing to do would be to end this paragraph with the 6,000 exoplanet discovery counterpart to 51 Pegasi b, but that's unfortunately not possible.

This brings us to the complexity of NASA's announcement. "Confirmed planets are added to the count on a rolling basis by scientists from around the world, so no single planet is considered the 6,000th entry," the agency said in a statement. "There are more than 8,000 additional candidate planets awaiting confirmation."

In fact, as of writing this article, we're technically at 6,007 exoplanets in NASA's alien world tally. The "new discovery" featured by NASA is the heftily named KMT-2023-BLG-1896L b, a Neptune-like world with a mass equal to about 16.35 Earths. NASA is also responsible for the bulk of those exoplanet finds, with its TESS (Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite) count being at 693 and now-retired Kepler Space Telescope having found over 2,600.

And even though it can be written with just a few keystrokes, each member of that 6,007-strong club represents an entire world comparable to the planets of our solar system, which scientists have been scrutinizing for centuries.

There are 2,035 Neptune-like worlds in that count, in reference to exoplanets with similar sizes to our solar system's very own Neptune and Uranus. These tend to have "hydrogen and helium-dominated atmospheres with cores of rock and heavier metals," according to NASA. ("Metals" doesn't necessarily mean metallic elements. Somewhat confusingly, in astronomy, that just refers to elements heavier than hydrogen and helium).

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

There are 1,984 gas giants (think Jupiter relatives) and 1,761 super-Earths in the court — the latter group is not to be confused with Earth 2.0 candidates. Super-Earths simply refer to exoplanets that are a little larger than Earth but still lighter than planets like Neptune and Uranus.

NASA's exoplanet count further includes 700 "terrestrial planets," or rocky worlds, and maybe most fascinatingly, seven of "unknown" types.

Indeed, breaking those categories down even further would require stretching your brain to a place where you can imagine a two-faced world half-covered in lava, an orb made of diamond that can regrow its atmosphere, one zipping through space at over 1 million mph (1.6 million kph) and the physical embodiment of hell.

"Each of the different types of planets we discover gives us information about the conditions under which planets can form and, ultimately, how common planets like Earth might be, and where we should be looking for them," Dawn Gelino, head of NASA's Exoplanet Exploration Program, located at the agency's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California, said in a statement. "If we want to find out if we’re alone in the universe, all of this knowledge is essential."

Still, in the agency's video about the milestone, an existential aspect of exoplanet-hunting is mentioned. "There's one we haven't found — a planet just like ours."

At least, not yet."

Monisha Ravisetti is Space.com's Astronomy Editor. She covers black holes, star explosions, gravitational waves, exoplanet discoveries and other enigmas hidden across the fabric of space and time. Previously, she was a science writer at CNET, and before that, reported for The Academic Times. Prior to becoming a writer, she was an immunology researcher at Weill Cornell Medical Center in New York. She graduated from New York University in 2018 with a B.A. in philosophy, physics and chemistry. She spends too much time playing online chess. Her favorite planet is Earth.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.