James Webb Space Telescope confirms 1st 'runaway' supermassive black hole rocketing through home galaxy at 2.2 million mph: 'It boggles the mind!'

"The forces that are needed to dislodge such a massive black hole from its home are enormous."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Astronomers have made a truly mind-boggling discovery using the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST): a runaway black hole 10 million times larger than the sun, rocketing through space at a staggering 2.2 million miles per hour (1,000 kilometers per second).

That not only makes this the first confirmed runaway supermassive black hole, but this object is also one of the fastest-moving bodies ever detected, rocketing through its home galaxy at 3,000 times the speed of sound at sea level here on Earth. If that isn't astounding enough, the black hole is pushing forward a literal galaxy-sized "bow-shock" of matter in front of it, while simultaneously dragging a 200,000 light-year-long tail behind it, within which gas is accumulating and triggering star formation.

"It boggles the mind!" discovery team leader Pieter van Dokkum of Yale University told Space.com. "The forces that are needed to dislodge such a massive black hole from its home are enormous. And yet, it was predicted that such escapes should occur!"

Article continues belowSupermassive black holes, which can reach masses billions of times that of the sun, are usually found at the hearts of their home galaxies, which they dominate with their immense gravity. The incredible speed of this supermassive black hole means it is around 230,000 light-years from its point of origin.

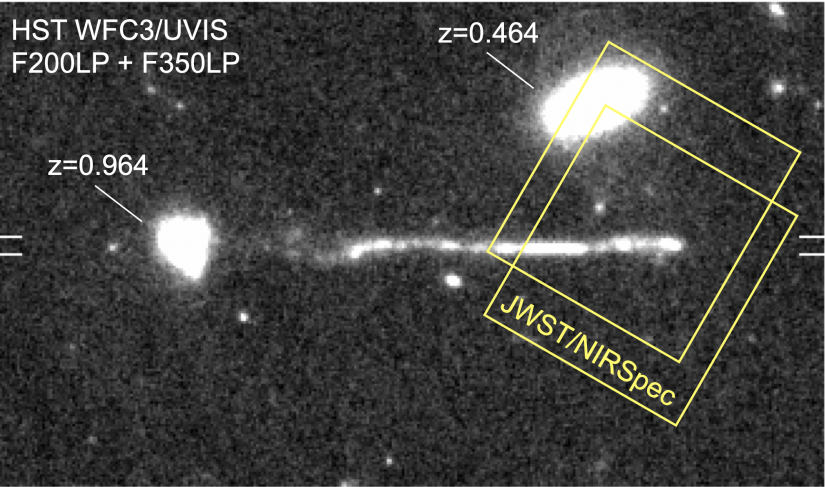

"This is the only black hole that has been found far away from its former home," van Dokkum said. "That made it the best candidate [for a] runaway supermassive black hole, but what was missing was confirmation. All we really had was a streak that was difficult to explain in any other way. With the JWST, we have now confirmed that there is indeed a black hole at the tip of the streak, and that it is speeding away from its former host."

How to spot a runaway

This now-confirmed runaway supermassive black hole was first identified by van Dokkum and colleagues back in 2023 using the Hubble Space Telescope, which spotted what appeared to be the wake of a massive body passing through space. Of course, like all black holes, this runaway is bounded by a one-way light-trapping surface called an event horizon, making it difficult to spot.

"The black hole is, well, black - and is very difficult to detect when it is moving through empty space. The reason why we spotted the object is because of the impact that the passage of the black hole has on its surroundings: we now know that it drives a shock wave in the gas that is moving through, and it is this shock wave, and the wake of the shock wave behind the black hole, that we see," van Dokkum said. "With the JWST, we discovered the huge displacement of the gas at the tip of the wake, where the black hole is pushing against it. The shock signatures are crystal clear, and there is just no doubt about what is happening here." The gas is pushed sideways away from the supermassive black hole at a velocity of hundreds of thousands of miles per hour (hundreds of km per second), a dynamical signature that the team saw with JWST.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"The velocity of the displaced gas is directly related to the velocity of the black hole, and this is how we determined the black hole's velocity from the JWST data," van Dokkum said. "It is moving at approximately 1000 km per second, faster than just about any other object in the universe. It is this high speed that enabled the black hole to escape the gravitational force of its former home."

How does a supermassive black hole 'go rogue?'

van Dokkum explained that two possible mechanisms could lead to a supermassive black hole being ejected from the heart of its own galaxy. Both scenarios begin when two galaxies collide and begin to merge, each bringing to the cosmic smash its own supermassive black hole. Both mechanisms are initiated when the supermassive black holes reach the center of the newly formed galaxy.

"The first mechanism is that the two black holes merge with each other, and that the gravitational radiation [gravitational waves] released in that merger imparts a powerful kick to the newly formed black hole. That kick could impart a speed of 1,000 km/s, enough to eject the black hole," van Dokkum said. "The second is a three-body interaction. That happens when one of the two galaxies had a pair of binary black holes at its center. When a third black hole enters the binary system, it becomes unstable, and one of the three black holes will get kicked out of the system."

The team believes that it is the first scenario that accounts for the runaway supermassive black hole in this instance. That would lead to a galaxy lacking a supermassive black hole at its center, which van Dokkum said is unlikely to impact said galaxy very much. However, this runaway supermassive black hole could have a huge impact on any other galaxy it encounters as it rockets through space.

"An encounter with another galaxy would be quite spectacular, mostly because of the huge, galaxy-sized shock wave that precedes the black hole," van Dokkum continued. "When this shock wave encounters the dense gas of another galaxy, it would compress and shock that gas and likely form a lot of new stars. It would be quite the show!"

Mergers between galaxies are common, occurring multiple times over the lifetime of a single galaxy. That means that ejected supermassive black holes may also be quite common, though population numbers vary based on how these collisions are modelled.

"Mergers happen often in the life of a galaxy; each galaxy with the size and mass of the Milky Way has experienced several during its lifetime. So black hole binaries should form pretty regularly. What we don't know is how quickly these binaries merge, if at all, and how often the resulting kick removes a black hole," van Dokkum said. "My view is empirical: now that we know how to look for them, we can find other examples - and then we can answer the question directly from data, by counting the number of escapes. The big thing is that black hole escapes lived purely in the realm of theory until now."Even though runaway supermassive black holes had been predicted by theory long before this discovery confirmed their existence, that doesn't mean these findings didn't deliver some unexpected twists.

"Everything about this research surprised me! I never expected to see such a thing, and confirming it with JWST was just incredible," van Dokkum said. "What we also had not quite appreciated is how much impact these escaping black holes have on the gas that they are moving through. In the wake, many new stars have formed from the shocked gas, about 100 million times the mass of the sun. This mode of star formation was unknown before, and it leads to a trail of stars far away from the galaxy, seemingly formed in empty space."

The Yale University researcher explained that the obvious next step for the team will be to search for more examples of runway black holes.

"You need space-based imaging to see them: the wake stood out to us because it is such a thin streak, and in ground-based images, it would be blurred beyond recognition," van Dokkum explained. "Fortunately, wide-field Hubble-quality imaging is just around the corner, thanks to the Roman Space Telescope, and, slightly blurrier, Euclid. Using machine learning algorithms to find thin streaks in the Roman data will be a cool project!"

The team's research has been submitted to The Astrophysical Journal Letters and is currently available as a pre-peer-reviewed paper on arXiv.

Editor's note: A previous version of this story described the runaway black hole as located in the Cosmic Owl galaxies, which is not the case.

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. whose articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space, Newsweek and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University. Follow him on Twitter @sciencef1rst.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.