Chasing a Solar Eclipse: Hitting the Bull's Eye at 44,000 Feet (First Person)

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

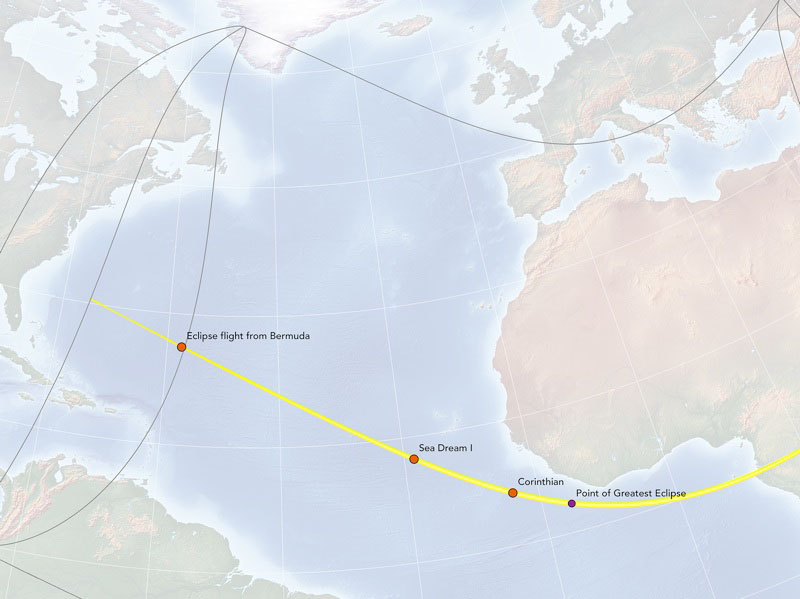

BERMUDA — On Nov. 3, as the moon's shadow raced across one-third of the Earth's surface, a small plane was trying to make a bit of history over the Atlantic Ocean.

The airplane would attempt to view the few seconds of totality — the total phase of the solar eclipse — at the very beginning of the eclipse path, where the shadow, moving at nearly 8,000 mph (12,875 km/h) was just touching down on Earth. (It slowed down considerably later in the path.)

As described in my eclipse preview story, was a first–of-its-kind eclipse flight, which would try to intercept the high-speed shadow at a nearly 90-degree angle, hitting a specific geographical point at a precise moment in time. Most eclipse flights, which have become fairly common each time there is a total eclipse, depart early, make their way into the eclipse path and fly with it, waiting for the shadow to catch up. They even extend the duration of the total portion of the eclipse in doing so, due to the plane’s speed. [See Cooper's amazing photos of the solar eclipse-chasing flight]

Prior to our flight, only once before had such a short eclipse been successfully viewed from an airplane. University of Arizona astronomer Glenn Schneider, one of the world's leading eclipse experts, viewed a zero-second eclipse, where the sun and moon were virtually the same apparent size, in 1986.

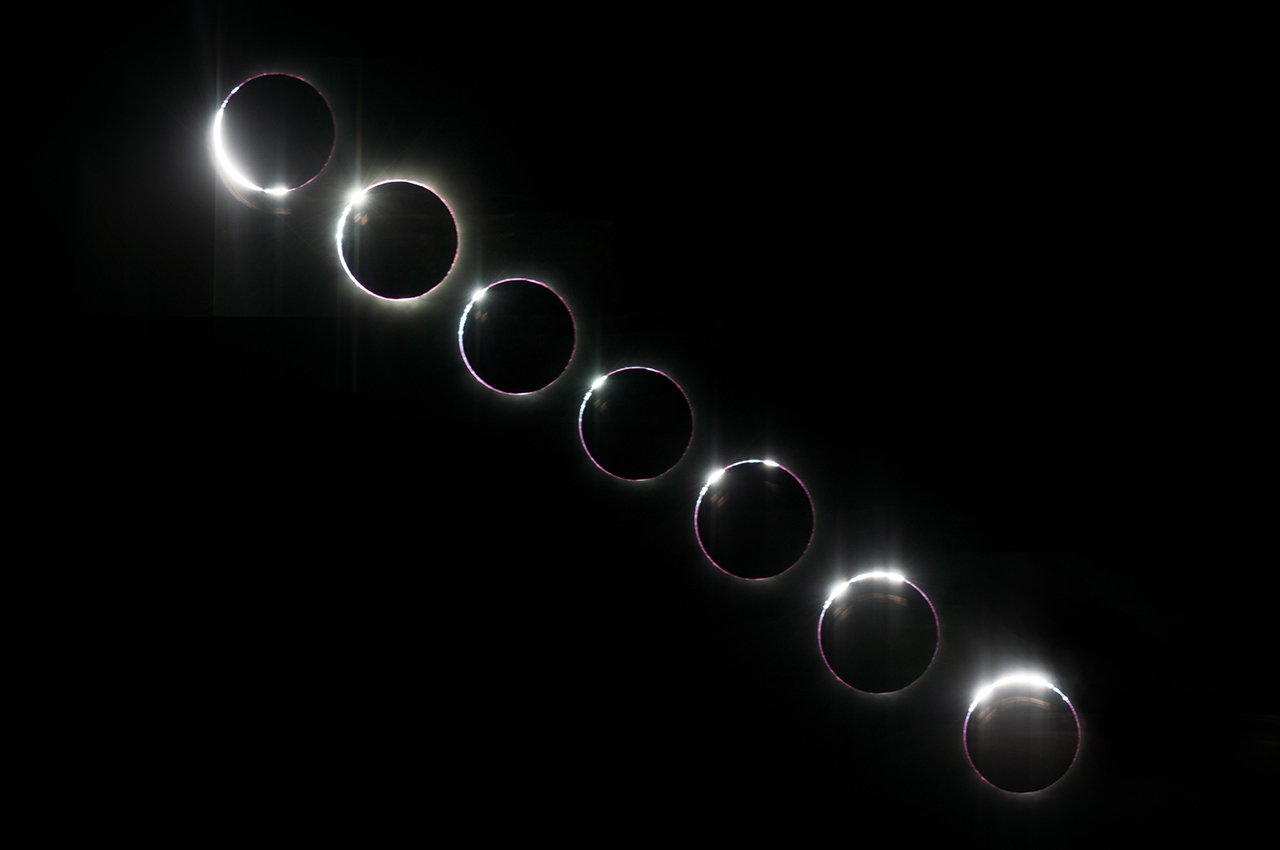

Photos from that spectacular but brief event show the moon ringed with tiny beads of sunlight, a phenomenon known as Bailey's Beads. These beads are, in fact, specks of sunlight passing between the mountains and valleys on the moon's surface. As in most eclipse flights, the plane waited in the path of the eclipse for the shadow to catch up.

But this would not be a possibility on our flight. The geometry of the Nov. 3 solar eclipse in this portion of the path meant that only the pilots would see it, out in front of the plane, if we flew with the path. So to accomplish this feat, our aircraft would have to intercept the path perpendicular to it, and do so at a precise instant with zero margin for error, due to the speed of the shadow at this location. Think of it as two cars meeting at an intersection, but traveling at super-high speed.

Schneider compared our intercept to a "bullet hitting a bullet" in some pre-flight correspondence.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

We would target our intercept for where the shadow crossed a point on Earth at 7:08 a.m. local time (11:08:00 GMT), a nice round number that made it easier to punch numbers into the navigational aids. We also had backup plans for intercepts farther west along the track at 11:07:00 and 11:07:30 GMT, in the event of strong headwinds or other weather. [Rare Hybrid Solar Eclipse Photos of Nov. 3, 2013 (Gallery)]

At our preferred location, we would get a maximum possible duration of about seven seconds of official totality, but this would require the aircraft being located right on the center line of the eclipse path at the precise instant the shadow moved across the area. We knew going into this that it would be tough to pull off.

With the planet traveling as fast as 600 mph (966 km/h), the duration of totality would shrink several seconds, perhaps even becoming zero seconds, if we were just one second early or late. Any more than that, and we would get only a partial eclipse of 99 percent at the greatest.

Getting the last seat

Just a few weeks before the flight, I was able to secure the final window aboard our aircraft. I arrived in Bermuda late in the afternoon of Nov. 2, and after checking out our aircraft and receiving a briefing from our pilots and group leaders, got a few short hours of sleep before our meeting time of 4:00 a.m.

The Dassault Falcon 900B and our group of 12 departed Bermuda at 5:35 a.m. local time on a straight-line path toward a spot some 600 miles (966 km) to the southeast of the island. Within minutes of taking off, preparations for the eclipse began in earnest. The few of us who planned to take photos of the eclipse, including myself, began unpacking our gear and setting up cameras at each of the plane’s windows. Several video cameras were positioned around the plane’s cabin and cockpit as well to capture the event.

One of the aircraft’s technicians was onboard and he quickly began removing seats to free up precious space for ourselves and our cameras on the small business jet. Outside the plane, as we raced southeast toward where the sun would come up, twilight began to present itself faster than on the ground. About a half-hour into the flight, the sun rose and the partial eclipse began, an event known as "first contact" in eclipse terms. We were now about an hour away from totality.

We were free to use the cockpit for photography as well, as long as we did not interfere with the pilots' work. Even without the eclipse, it was a special experience to watch the sun begin to shrink through the flight deck windows — a view few get.

Chasing the eclipse

As the clock ticked down, tension began to build. My two cameras — one with a wide angle that would capture the eclipsed sun in the sky with the plane’s wing in the foreground and another with a telephoto lens — were in place.

We arrived at the pre-determined eclipse position early, as planned the night before, and executed two practice loops before aligning on the right path for the right moment. This gave the pilots a chance to observe the wind conditions the plane was flying through. Everything was looking perfect. [Solar Eclipses: An Observer's Guide (Infographic)]

With about three minutes to go, the plane was set on its final straight-line run. Out the window, the sun had shrunk to nothing more than a thin crescent. At two minutes, the plane hit a few bumps of turbulence; the cloud deck from a weather system was only just below us, even at an altitude of 44,000 feet (13,411 meters). The pilots turned the plane slightly to get away from the bumps but kept us on the right path.

Suddenly, the thin crescent of sun began to break up into small sections, Bailey's Beads, and I began firing the camera at high speed. Several beads became one — the "diamond ring" effect in eclipse terms — and as quickly as this happened, another appeared on the other side of the moon’s disk, and the beads began to reappear.

This meant that, technically, we were likely about one second off from hitting the precise target. But everyone, including myself, let out a cheer! We had done it within one second of the plan and were thrilled. For a few instants, the sun's corona became visible alongside the beads and was captured in our photos.

Even after the eclipse was over, some debate ensued about whether or not we hit an instant of totality. We must now look at the data and see, if we can, just where we were and at what moment, down to a fraction of a second.

But as far as the group and eclipse community is concerned, our flight was a great success even if we were one hair off of being dead-center.

With tension eased, the plane turned and the aircraft began its 600-mile flight back to Bermuda, where we landed an hour later. The group posed for a photo in front of our plane, and T-shirts commemorating our flight were handed out. It was all over as fast as it began.

Special thanks go to veteran eclipse chasing friend and astronomer Don Hladiuk of Calgary and Robert Minor of California for help obtaining these photos. Thanks also go to the pilots of our aircraft and expert eclipse navigator Xavier Jubier, who was aboard of flight as well.

Editor's note: If you snapped an amazing photo of the Nov. 3 solar eclipse or any other celestial sight that you'd like to share for a possible story or image gallery, please contact managing editor Tariq Malik at spacephotos@space.com.

You can follow space photography Ben Cooper @LaunchPhoto or at LaunchPhotography.com. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on SPACE.com.

Ben Cooper is an award-winning photographer based in Cape Canaveral, Florida, where he has photographed over 400 launches to date. As an official photographer for some of the biggest launch providers, as well as for NASA and several media outlets over the past 20+ years, he has captured many of the most well-known and iconic space mission photos taken in the last two decades. Ben is the author of the 2019 book Launch Photography and was the 2019 winner of the Kolcum Award "for excellence in telling the space story along Florida’s Space Coast and throughout the world."