Scientists discover cosmic 'scar' in interstellar clouds left by a close shave between our sun and 2 intruder stars

"It’s kind of a jigsaw puzzle where all the different pieces are moving."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

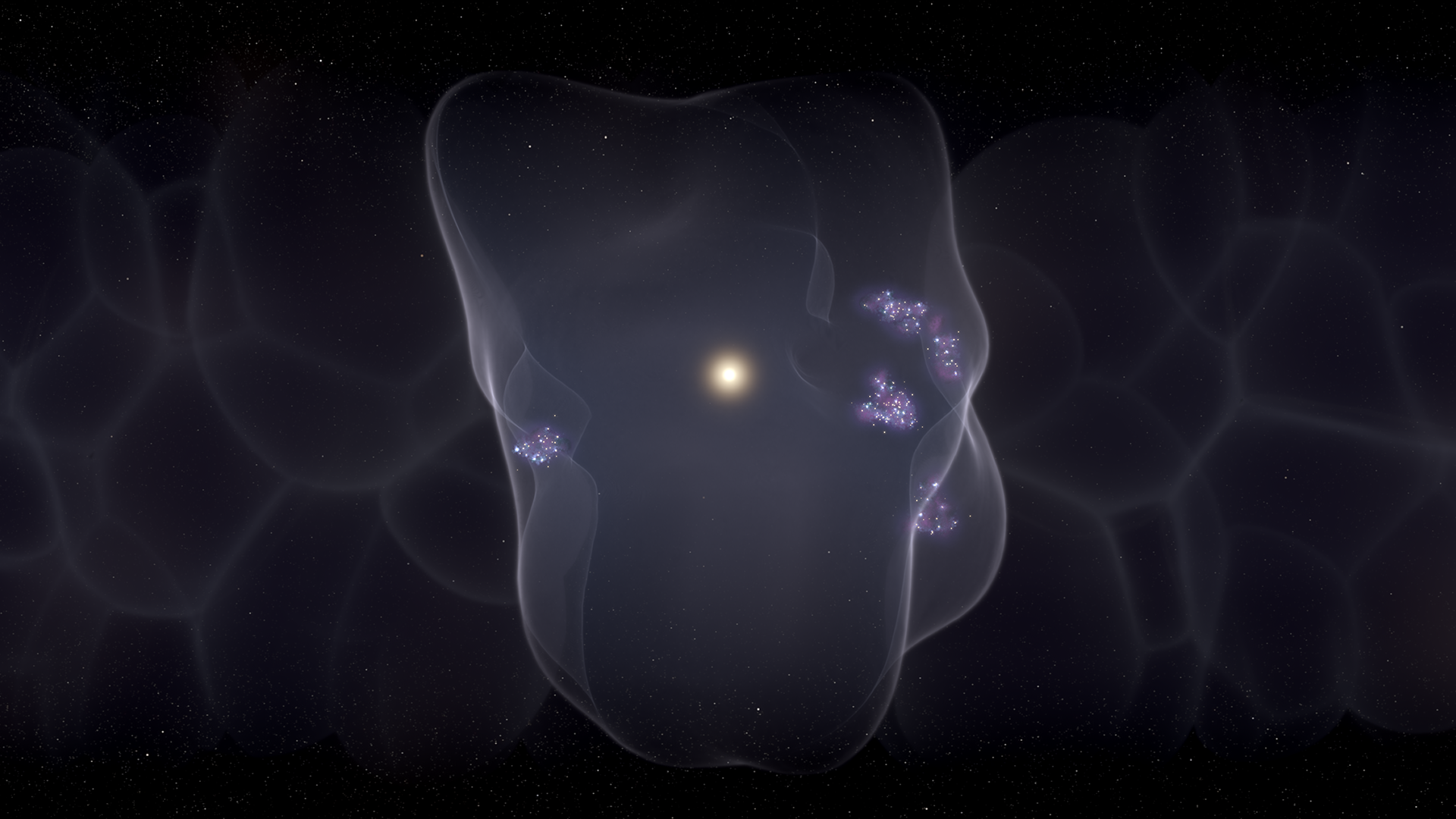

Astronomers have discovered that the sun had a close encounter with two blazingly hot massive stars around 4.4 million years ago. The discovery was made thanks to a "scar" left by the event in swirling clouds of gas and dust just beyond the solar system. Not only does this research reveal more about the solar system's immediate celestial environment, but it could also shed light on how surrounding features in that environment played a role in the evolution of life on Earth.

To make this discovery, the team of astronomers had to take into account the motions of these "local interstellar clouds," which stretch out for around 30 light-years, the sun, and the intruder stars, which now dwell 400 light-years from Earth in the front and rear "legs" of the constellation Canis Major (the Great Dog). That's tricky because the sun alone is rocketing through space at 58,000 miles per hour (93,000 km/h), or about 75 times as fast as the speed of sound at sea level here on Earth.

"It's kind of a jigsaw puzzle where all the different pieces are moving," team leader Michael Shull of the University of Colorado Boulder said in a statement. "The sun is moving. Stars are racing away from us. The clouds are drifting away."

Beyond the local interstellar clouds and their wispy clumps of hydrogen and helium atoms in the form of gas and dust, the solar system sits within a region of the Milky Way that is relatively devoid of such matter, called the "local hot bubble."

Understanding these regions could be important in comprehending how life was afforded the conditions it needed to prosper on Earth.

"The fact that the sun is inside this set of clouds that can shield us from that ionizing radiation may be an important piece of what makes Earth habitable today," Shull explained.

To investigate this influence, Shull and colleagues set about modelling the forces that have shaped our region of the Milky Way. This involved looking closely at two stars in Canis Major known as Epsilon Canis Majoris, or Adhara, and Beta Canis Majoris, or Mirzam. The team found that it is likely these two stars would have raced past the sun roughly 4.4 million years ago, coming as close as 30 light-years to our star. While that is a tremendous distance in terrestrial terms, equivalent to around 175 trillion miles (281 trillion km), it is a close passage in cosmic terms and in a galaxy that is 105,700 light-years wide.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Such a close pass would have made these stars quite visible from Earth, scientists say. "If you think back 4.4 million years, these two stars would have been anywhere from four to six times brighter than Sirius is today, far and away the brightest stars in the sky," Shull said.

These stars are each much larger than the sun, about 13 times as massive as our star. They are also far hotter than the sun, with temperatures up to 45,000 degrees Fahrenheit (25,000 degrees Celsius), making the 10,000 degrees Fahrenheit (5,500 degrees Celsius) temperature of the sun look relatively balmy. When these massive, powerful, but short-lived stars passed through our cosmic backyard, they emitted powerful ultraviolet radiation that ripped away electrons from atoms in the local interstellar clouds, a process called "ionization." The removal of negatively charged electrons left these hydrogen and helium atoms with a positive charge — the "scar" that the team was able to detect.

The team's research solves a long-standing mystery about the local interstellar clouds, which emerged when astronomers previously found that 20% of the hydrogen atoms and 40% of the helium atoms in these clumps of gas and dust had been ionized, an unusually high level of ionization, especially for helium.

The team theorizes that these stars had assistance in the ionization of these clouds from at least four other sources of ultraviolet radiation. These include three white dwarf stars, the type of stellar remnant left over when stars around the size of the sun die, and the local hot bubble itself.

That is because this underdense region of gas and dust is believed to have been cleared by the explosive supernova deaths of between 10 and 20 stars. Those supernovas heated the gas, causing the local hot bubble to emit ionizing radiation in the form of X-rays and ultraviolet radiation, roasting the local interstellar clouds around the solar system.

The ionization of these clouds won't last forever, fading as the hydrogen and helium atoms regain their neutral electrical charge by picking up loose electrons. This process could take around a few million years.

Epsilon and Beta Canis Majoris are also living on borrowed time. While the 4.6 billion-year-old sun will live around another 5 billion years before sputtering out as a white dwarf, massive stars like these burn through their fuel for nuclear fusion much faster. It is likely that both Epsilon and Beta Canis Majoris will go supernova in the next few million years.

While they are too distant to pose any risk to Earth, the explosive deaths of these stars could provide a spectacular show for any lifeforms still left on Earth. "A supernova blowing up that close will light up the sky," Shull said. "It'll be very, very bright but far enough away that it won’t be lethal."

The team's research was published at the end of November in The Astrophysical Journal.

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. whose articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space, Newsweek and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University. Follow him on Twitter @sciencef1rst.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.