Sun unleashes intense X-class solar flare, triggering radio blackouts across Australia

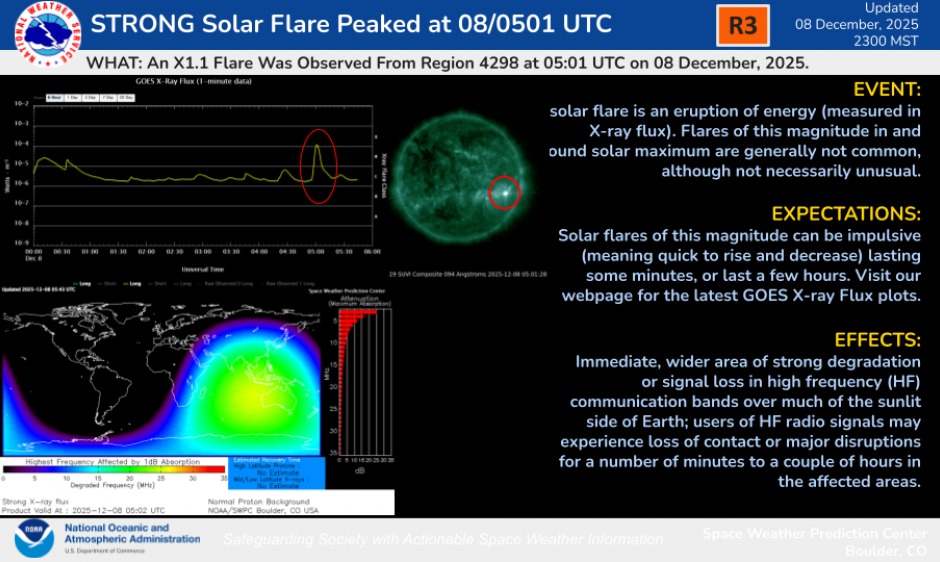

The powerful X1.1 solar flare from sunspot region 4298 sparked strong radio blackouts on the sunlit portion of Earth at the time of eruption.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

The sun erupted with a powerful X1.1-class solar flare in the early hours of this morning (Dec. 8), briefly knocking out radio communications across Australia and parts of southeast Asia.

The impulsive eruption, which peaked at 12:01 a.m. EST (0501 GMT), came from sunspot region AR4298 as it makes its way towards the sun's western limb. It will rotate out of view in the next couple of days.

A coronal mass ejection (CME) — a plume of plasma and magnetic field — was hurled into space alongside the eruption. However, early analyses of satellite coronagraph imagery suggest this CME is not Earth-directed.

The solar flare occurred during an already active week on the sun. Several CMEs from earlier solar flares are forecast to impact Earth between Dec. 8-9, prompting space weather forecasters at NOAA's Space Weather Prediction Center and the U.K. Met Office to issue geomagnetic storm watches, including a chance of strong-moderate (G2-G3) level storming, which could see northern lights visible at high to mid-latitudes.

What are solar flares?

Solar flares are caused when magnetic energy builds up in the sun's atmosphere and is released in an intense burst of electromagnetic radiation.

They are categorized by size into lettered groups according to strength:

- X-class: The strongest

- M-class: 10 times weaker than X

- C, B and A-class: Progressively weaker, with A-class flares typically having no noticeable effect on Earth.

Within each class, a numerical value indicates the flare's relative strength. The Dec. 8 flare came in at X.1.1, making it an X-class event.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

How does it cause radio blackouts?

When radiation from a solar flare reaches Earth, it ionizes the upper atmosphere which can disrupt shortwave radio communications on the sunlit side of the planet.

Normally, high-frequency radio waves travel long distances by bouncing off the ionosphere's higher, thinner layers. But during a strong flare, the lower, denser parts of the ionosphere become highly ionized instead. Radio waves passing through these layers collide more often with particles, losing energy as they go. As a result, high-frequency radio signals can fade, become distorted or disappear entirely according to NOAA.

Daisy Dobrijevic joined Space.com in February 2022 having previously worked for our sister publication All About Space magazine as a staff writer. Before joining us, Daisy completed an editorial internship with the BBC Sky at Night Magazine and worked at the National Space Centre in Leicester, U.K., where she enjoyed communicating space science to the public. In 2021, Daisy completed a PhD in plant physiology and also holds a Master's in Environmental Science, she is currently based in Nottingham, U.K. Daisy is passionate about all things space, with a penchant for solar activity and space weather. She has a strong interest in astrotourism and loves nothing more than a good northern lights chase!

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.