Rare solar flare caused radiation in Earth's atmosphere to spike to highest levels in nearly 20 years, researchers say

Radiation levels at airline flight altitudes briefly reached levels that could be potentially harmful to pregnant women.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

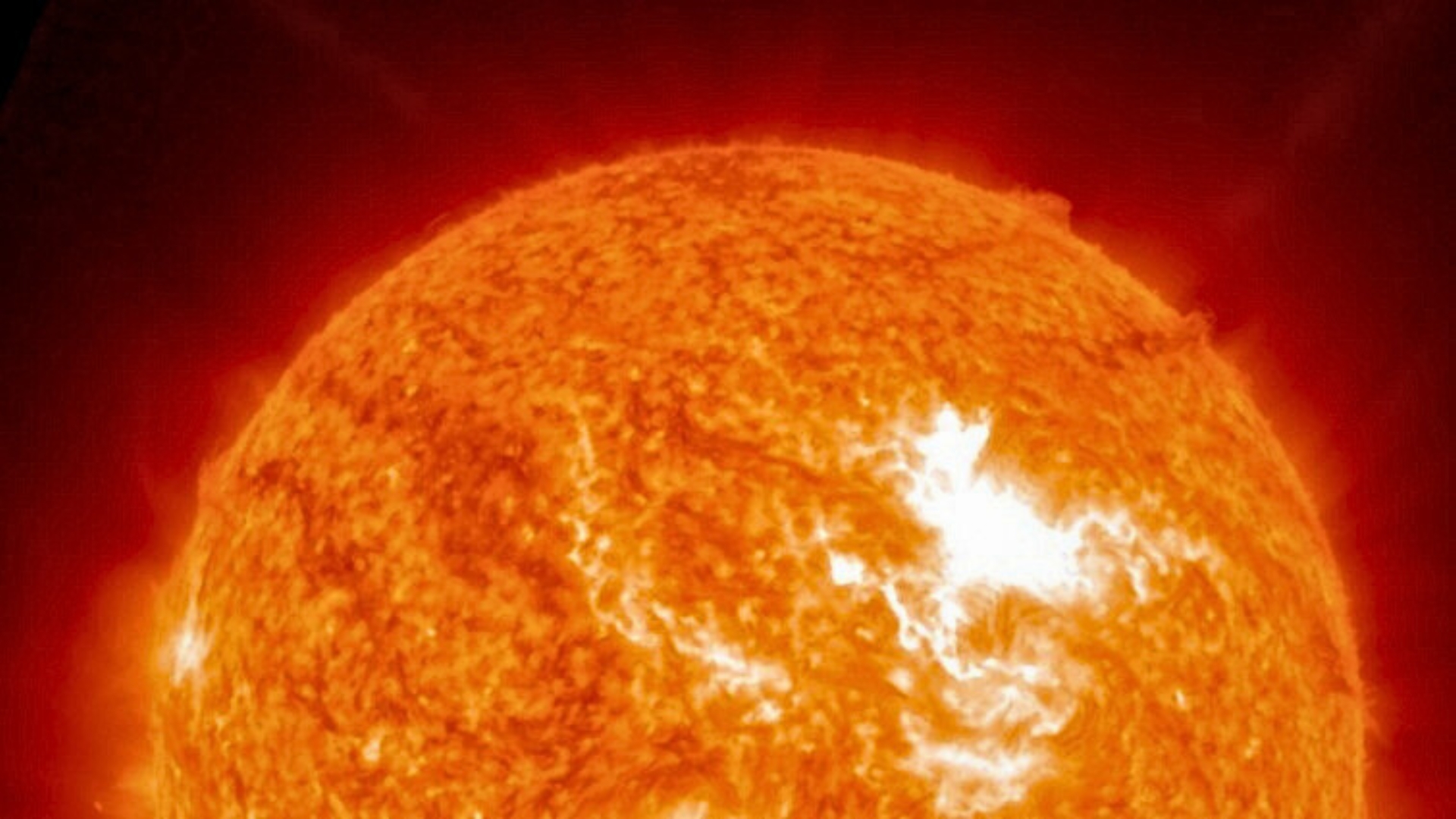

Radiation levels in Earth's atmosphere rose to the highest level in nearly two decades in November after a rare solar super-flare pummeled the planet with high-speed particles from the sun. The solar flare, an extremely bright flash of light, erupted from the AR4274 sunspot on Nov. 11. Classified as a powerful X5.1, the flare followed a series of milder flares and coronal mass ejections (CMEs) that treated skywatchers to mesmerizing aurora displays as far south as Florida.

Apart from being the most intense solar flare of 2025 to date, the X-class flare also unleashed a stream of high-speed protons and other energetic particles toward our planet, something very few solar flares do. This year, about 20 X-flares hit Earth — but only the one from Nov. 11 was accompanied by the high-speed proton stream. That day, when Earth-based monitors began showing elevated radiation levels, researchers released several stratospheric balloons with sensors to see how radiation levels evolved throughout the atmosphere.

They found that at altitudes where most commercial aircraft travel — around 40,000 feet (12 kilometers) — radiation briefly rose to levels ten times higher than the normal cosmic-ray-related background. If a pregnant woman were to be exposed to such radiation levels for more than 12 hours, she would have exceeded a limit officially considered as safe for a fetus. Fortunately in this case, the worst was over in about two hours, according to Benjamin Clewer, a space weather researcher at the University of Surrey in the U.K. "Typically, these events peak right at the beginning and that might only last about half an hour," Clewer told Space.com. "In this case, the event officially finished in 15 hours, but only the first two hours were significant."

CMEs also expel clouds of energetic particles into interplanetary space. Those particles, contained in clouds of magnetized plasma, take days to reach the planet. The protons unleashed by a solar flare, however, travel at nearly the speed of light and arrive within minutes, Clewer said.

When those energetic protons hit the top of Earth's atmosphere, they interact with molecules of air, triggering showers of secondary, less energetic particles including neutrons, muons and electrons. Such particles constantly trickle down onto Earth's surface as a result of the battering our planet experiences due to cosmic rays that arrive from the most distant parts of the galaxy. But when a stream of solar protons hits, radiation levels on Earth's surface and around the planet suddenly spike. The phenomenon is called a Ground Level Event (GLE) and is rather rare. In fact, since measurements began in the 1940s, only 77 such GLEs have been registered, according to Clewer.

Scientists don't understand why some solar flares cause GLEs and some do not and therefore cannot predict when a spike in radiation occurs.

"We don't understand the physics of it that well as to why some solar flares eject these really high speed particles and other ones don't," said Clewer, whose team made measurements of the event that revealed its intensity.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The GLE on Nov. 11, however, was only a mild example of what the sun is capable of. The most intense GLE ever detected happened in 1956 and was sixty times more intense. Even stronger ones, over a thousand times as intense as the Nov. 11 GLE, are possible, as evidenced by radioisotope studies in tree rings.

The GLEs are not only potentially dangerous for human health (in addition to the risk to unborn babies, radiation exposure increases the risk of cancer in all humans), they can also wreak havoc with aircraft electronics.

Only two weeks before the Nov. 11 GLE, a JetBlue Airbus traveling over Florida experienced a sudden loss of altitude that was later attributed to possible malfunctions of onboard electronics caused by high-energy particles from space. Researchers are concerned that a full-on GLE could make aircraft electronics go haywire en masse, increasing the risks of dangerous situations aboard hundreds or perhaps even thousands of planes. The JetBlue incident resulted in multiple injuries to passengers that required medical care.

"The pilots could have different alarms going off in the cockpit at the same time," Clewer said. "They might be having to turn off and reset different bits of equipment. In the worst case scenario, they might have to fly manually."

The researchers are campaigning for all aircraft to be equipped with radiation monitors to help pilots understand what's going on. During severe radiation events, radio links that allow communication with ground control are likely to be disrupted too, preventing the pilots from learning about the cause of the problems. Because GLEs come suddenly and can't be predicted, many aircraft will be caught in those events mid-air.

"If you're in the air and still can communicate with air traffic, you could descend to a lower altitude or change your latitude," Clewer said. "But there is a likelihood that the pilots won't be able to talk on the radio and have to do all the other mitigations on top of that."

Tereza is a London-based science and technology journalist, aspiring fiction writer and amateur gymnast. She worked as a reporter at the Engineering and Technology magazine, freelanced for a range of publications including Live Science, Space.com, Professional Engineering, Via Satellite and Space News and served as a maternity cover science editor at the European Space Agency.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.