108 million degrees! Solar flares are far hotter than thought, study suggests

The new finding may solve an "astrophysics mystery that has stood for nearly half a century."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

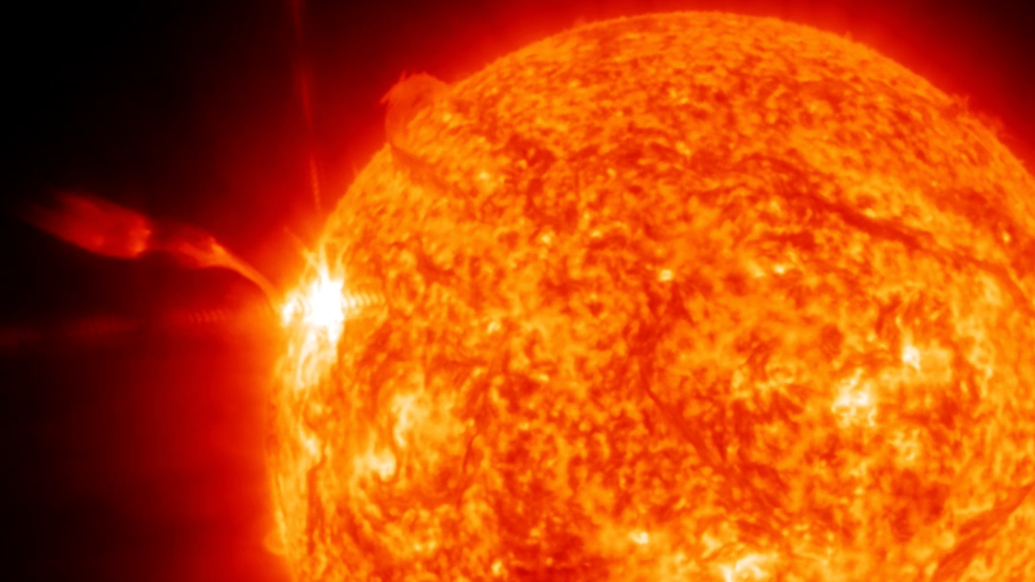

Our sun's fiery flares are even more extreme than scientists had thought, blasting particles to temperatures six times hotter than earlier estimates, according to new research.

Solar flares are colossal explosions in the sun's atmosphere that hurl out bursts of powerful radiation. These events are notorious for disrupting satellites, scrambling radio signals and potentially posing dangers to astronauts in space.

Now, a team led by Alexander Russell of the University of St. Andrews in Scotland reports that particles in the sun's atmosphere heated up by flares can reach a staggering 60 million degrees Celsius (108 million degrees Fahrenheit) — tens of millions higher than earlier predictions, which typically put such temperatures between 10 million and 40 million degrees Celsius (18 million to 72 million degrees Fahrenheit).

"This appears to be a universal law," Russell said in a statement. The effect has already been observed in near-Earth space, the solar wind and in simulations, he added, but until now, "nobody had previously connected work in those fields to solar flares."

Since the 1970s, astronomers have been puzzled by a strange feature in the light from solar flares. When split into colors using powerful telescopes, the telltale "spectral lines" of different elements look much broader, or blurrier, than theory predicts.

For decades, scientists chalked this up to the turbulence known to occur in the sun's plasma. Like the chaotic bubbling of boiling water, the swift, random motions of charged particles in plasma can, in theory, shift light in different directions as they move. But the evidence never fully matched up, the new study notes. Sometimes the broadening appeared before turbulence could form, and in many cases the shapes of the lines were too symmetrical to match turbulent flows, according to the paper.

In their new study, Russell and his team suggest a simpler explanation: the solar particles affected by flares are simply far hotter than previously thought.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Using experiments and simulations of magnetic reconnection — the snapping and realignment of magnetic field lines that powers flares — the researchers found that, while electrons may reach 10 million to 15 million degrees C (18 million to 27 million degrees C), ions can soar past 60 million degrees C (108 million degrees F). Because it takes minutes for electrons and ions (which are atoms or molecules with an electrical charge) to share their heat, this temperature gap lasts long enough to shape the behavior of flares, according to the study.

At such extreme temperatures, ions zip around so quickly that their motion naturally makes the spectral lines look wider, "potentially solving an astrophysics mystery that has stood for nearly half a century," Russell said in the statement.

The finds are not merely an academic exercise; they also carry implications for predicting space weather. If scientists have been underestimating the energy stored in flare ions, forecasts of space weather may need to be revised. Improved models could give satellite operators, airlines and space agencies more accurate information and extra time to prepare for dangerous solar events, scientists say.

The research also calls for a new generation of solar models, ones that treat ions and electrons separately instead of assuming a single uniform temperature. This "multi-temperature" approach is already common in other plasma environments, such as Earth's magnetic field, but has rarely been applied to the sun, the study notes.

This research is described in a paper published earlier this month in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

Sharmila Kuthunur is an independent space journalist based in Bengaluru, India. Her work has also appeared in Scientific American, Science, Astronomy and Live Science, among other publications. She holds a master's degree in journalism from Northeastern University in Boston.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.