James Webb Space Telescope watches 'Jekyll and Hyde' galaxy shapeshift into a cosmic monster

"Virgil has two personalities, its 'good' side – a typical young galaxy quietly forming stars. But Virgil transforms into the host of a heavily obscured supermassive black hole, pouring out immense quantities of energy."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Jekyll and Hyde and the Wolfman better watch out. They have stiff new competition for the most fearsome and beastly transformation from mild-mannered to raging beast from the galaxy known, rather unintimidatingly, as "Virgil."

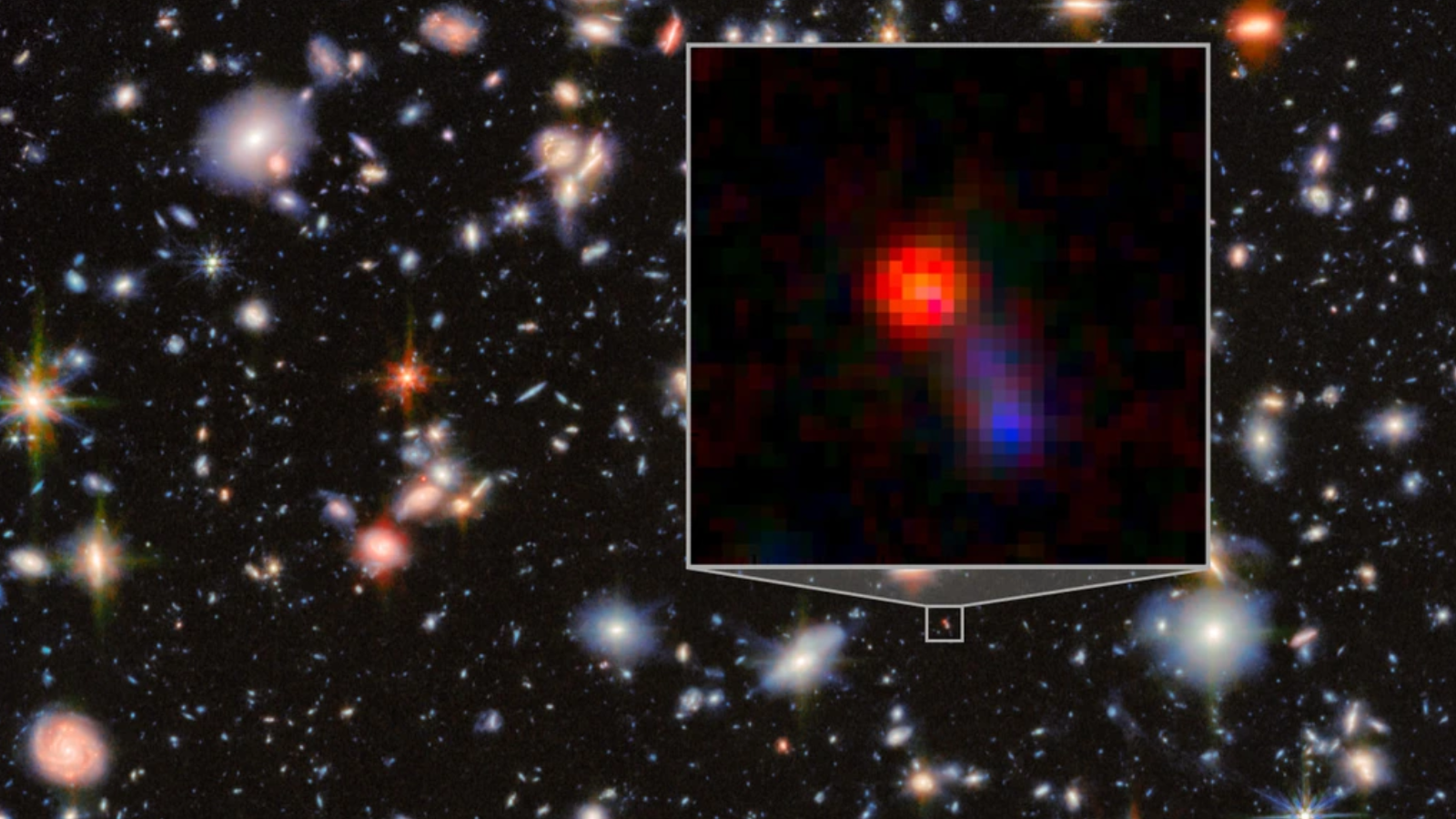

Using the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), astronomers watched as the Virgil transformed before their eyes, revealing its monstrous nature and a supermassive black hole at its heart that is feeding on matter at an incredible rate. The black hole now appears far too massive for its host galaxy to support, placing it in a rare category of "overmassive" black holes that challenge leading models of how galaxies first formed and of how they nurture supermassive black holes at their cores, growing in lock step.

"[The] JWST has shown that our ideas about how supermassive black holes formed were pretty much completely wrong," co-team leader George Rieke, of the University of Arizona, said in a statement. "It looks like the black holes actually get ahead of the galaxies in a lot of cases. That's the most exciting thing about what we're finding."

Article continues belowVirgil belongs to a mysterious class of objects known as "Little Red Dots," galaxies that JWST has been discovering in large numbers around 600 million years after the Big Bang. These objects seem to disappear by the time the universe reaches an age of around 2 billion years. Quite what these galaxies are is a mystery, but the more puzzling question is why they disappeared around 1.6 billion years after they reached their largest population.

The study of Virgil could solve this twin dilemma by suggesting what form Little Red Dots may have transformed into, allowing us to identify their descendants in the modern universe.

The research also suggests that some terrifying cosmic monsters may be out in the universe, hiding in plain sight.

An infrared monster

Light comes in multiple wavelengths, which astronomers often use to reveal different characteristics about the same objects. The true nature of Virgil was only revealed when astronomers studied this galaxy in infrared light, invisible to the human eye, using the JWST's Mid-infrared Instrument (MIRI).

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"Virgil has two personalities," Rieke explained. "The UV and optical show its 'good' side – a typical young galaxy quietly forming stars. But when MIRI data are added, Virgil transforms into the host of a heavily obscured supermassive black hole pouring out immense quantities of energy."

This violent side of Virgil had remained hidden in other wavelengths of light because its heart, where the ravenous supermassive black hole dwells, is shrouded in thick clouds of dust. This dust is very good at absorbing ultraviolet and visible light, but infrared light is able to give it the slip. That means viewing Virgil in infrared gives a more complete picture of what is happening at its core.

"MIRI basically lets us observe beyond what UV and optical wavelengths allow us to detect," team co-leader Pierluigi Rinaldi of the Space Telescope Science Institute said. "It's easy to observe stars because they light up and catch our attention. But there's something more than just stars, something that only MIRI can unveil."

The research may have wider implications for astronomers, suggesting there could be a whole population of dust-obscured supermassive black hole monsters out in the cosmos, which may have played a significant early role in the evolution of the universe.

As of yet, scientists aren't aware of any other cosmic monsters like Virgil roaming the early universe, but that could be because the way we study the cosmos allows them to fool us with their mild-mannered alter egos.

"Are we simply blind to its siblings because equally deep MIRI data have not yet been obtained over larger regions of the sky?" Rinaldi said. "JWST will have a fascinating tale to tell as it slowly strips away the disguises into a common narrative."

The team's research was published on Dec. 8 in the journal Nature Astronomy.

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. whose articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space, Newsweek and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University. Follow him on Twitter @sciencef1rst.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.